A covert attack mounted by a not-very-well-disguised assailant has shocked the art world, and given history’s most famous smile a very sudden, very messy facial. An official statement from the Louvre reports that the protective glass that surrounds the Mona Lisa bore all of the impact, and that the painting remains unharmed, but the high profile smear is bound to leave a lasting impression on the public perception of the prior scion of beauty and innocence.

While the nature of “priceless” works of art is that they can never be truly valued, either before or after their desecration, The Deep Dive isn’t going to let that stop us.

1519: The unfinished magnum opus of a dying master

King Francis I of France was a forerunner to modern patrons of the arts, who support artists and their art as a public, social good, while using that support to amass a collection of works that have the potential to become generational assets of enormous monetary value, long after the artists die hungry. In Francis’ time, classic art wasn’t classic yet, it was just plain art, and Francis liked to think he had an eye for what was good, so he picked up stuff he liked while warring with the collection of city states that is now Italy.

In 1515, Leonardo da Vinci was in Rome, and on the outs with the Pope. Francis brought Leonardo back to France with him as a sort of war trophy. It was an old, beat-up Leonardo, on the downslope from a stroke that might have paralyzed his right hand, so the King couldn’t have expected much production from da Vinci, but court artists are something of a package deal. Leonardo came to France with a studio full of talented apprentices and works in progress, including an unfinished commission portrait of the wife of a Venetian silk merchant: one Madonna Lisa Del Gioconda.

Mona Lisa’s Value: unclear

Francis set Leonardo up at Château du Clos Lucé and gave him the run of the place. Leonardo liked fiddling with the Mona Lisa, and kept working on it despite stroke-induced paralysis until he died four years after coming to France at age 67.

1519: A new addition to the Royal art collection of King Francis I

Leonardo had willed his masterpiece to his pupil and companion Andrea Salaì, along with a vineyard he owned in Milan, but King Francis wasn’t going to let “La Joconde,” get away. Accounts differ on whether the painting was seized from Salaì under a tax lien or whether Francis paid for it in cash, but the accepted first price the Mona Lisa changed hands for, after Leonardo’s death in 1519, was 4000 gold florins; equivalent to 450 troy ounces of gold. At the June 2022 spot price, USD $832,950.

Mona Lisa’s Value: 450 oz of gold

Salaì died in Milan seven years later from wounds sustained in a crossbow duel.

1790s: bone of contention in the French Revolution

Then, as now, original artwork was an investment made by people who had run out of places to put their money, and wanted to show the world that their children’s children had taste. Francis’ collection remained the property of the French monarchy for nearly 300 years. The collection grew along with the Crown’s wealth and, by 1741, art critics and pamphleteers were calling for the Royal collection to be displayed publicly, which it was.

Louis XV held viewings of 96 curated works periodically. “The King’s Paintings” were a hot ticket, and when the showings closed down, the French people, who were in a cranky mood at the time, agitated for the Royal collection to be displayed permanently.

Plans were drawn up in 1776 to convert La Grande Galerie of the Louvre – a Parisian fortress – into a museum where the art could be displayed. It moved about as fast as any government project until 1791, when Louis XVI, who was holding on to the throne by virtue of having agreed to a constitution drawn up to appease a mob who had just stormed the Bastille, suddenly came around on the idea that it was a shame to keep all that beautiful art cooped up where it couldn’t be enjoyed by everybody, but had trouble convincing anyone his heart was really in it.

By 1792, the newly formed French National Assembly declared the Royal Collection to be national property, and expedited the Louvre Museum plans. A fortress in the middle of town was an ideal place for it all to be guarded and cared for, away from the sticky fingers of starving mobs and from certain unpopular royalty known to be looking for a way out of town. By January of 1793, it was decided that Louis XVI would best serve his country as a high profile example. The Louvre opened officially in August.

Mona Lisa’s Value: A king’s life (potentially)

The Mona Lisa has been the property of the People of France ever since. It mostly stayed in the Louvre, but went on various adventures as it was hidden from invading armies and briefly hung in Napoleon’s bedroom. It spent another couple of hundred years as one of many original works of Renaissance masters in the Louvre, but one of only five Leonardos. Today, there are fewer than 25 surviving finished works confirmed to be by Leonardo.

1913: Stolen goods

By the 1900s, it was still only sophisticated intelligentsia that could impress each other by knowing and caring about fine art. Nobody dared put a price on any of the classic works in the Louvre, because they weren’t for sale in the legal marketplaces of polite society. The Mona Lisa was well-known in the upper crust, but not yet a household name. Its rocket ride to a permanent spot on the top of the art charts was launched by an Italian man who either knew or discovered that the surest way to get the unwashed masses excited about fine art is with a heist.

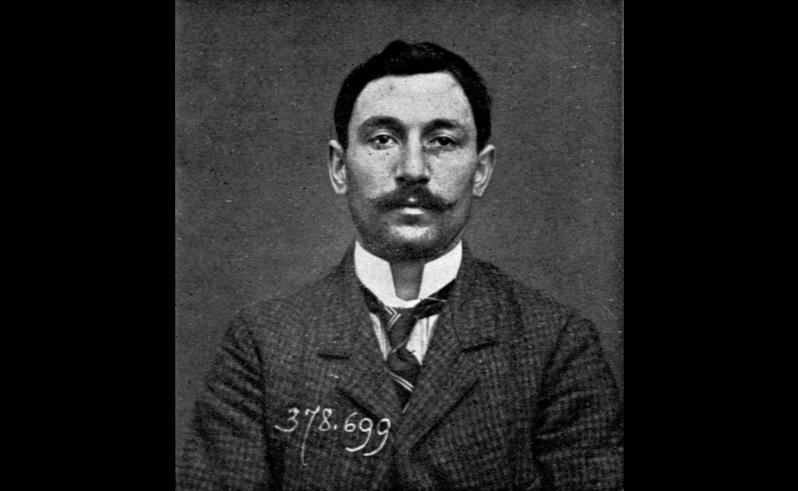

In 1911, Vincenzo Peruggia, a former Louvre worker, dressed himself in a white smock that made him part of the same background noise as the rest of the help, walked in through the service entrance, hung around looking busy until everyone else left, plucked the Mona Lisa off the wall, removed it from its frame, draped the smock over it, and walked back out through the service door.

The theft caused a media sensation, and pictures of the picture were on every front page in the world. The French authorities brought high profile art scene troublemakers Guillome Appolinaire and Pablo Picasso in for questioning and eventually let them go, presumably admitting to themselves that they never really had anything to go on in the first place, and were looking at a cold trail.

Peruggia hid the hottest stolen goods in the world in a steamer trunk in his Paris apartment, and just laid low. He was caught two years later in 1913, when he tried to sell it to a gallery owner in Florence. Italian authorities gave the Mona Lisa back to the Louvre, and Peruggia ended up doing seven months in jail. He managed to make himself into a national hero by claiming that he had stolen the painting so that he could repatriate it to Italy.

Mona Lisa’s Value: The love of a nation

It’s more likely that Peruggia did it for the money, then found out the hard way that the only way to move something with that high of a profile is to have a buyer arranged before the job. But it’s also possible that his fense just up and vanished.

1932: Plot device in a questionable news item

In 1932, the Saturday Evening Post ran a second hand account from an Argentinian con man named Eduardo de Valfierno, who claimed to have been dealing in forged art in the years leading up to Peruggia’s theft, and to have masterminded the heist. Typically, a forged copy of anything prominent would be hard to sell, because a buyer would be well aware that the original was on display somewhere.

The un-verifiable story, recounted by SEP writer Ken Decker, has de Valfierno commissioning six Mona Lisa copies, having partners smuggle them into New York one by one, telling their collector clients that he was about to have something great for them, then commissioning Peruggia to lift the original, and just not calling him back.

The press had a field day, and the Mona Lisa went from being some artifact in a stuffy French museum to the centrepiece in an international art caper, giving the copies made by the syndicate immediate value and a lustre of authenticity to their art collector marks.

Mona Lisa’s Value: unchanged

None of de Valfierno’s gang’s alleged forgeries have ever surfaced, and nobody can say for certain whether or not he existed outside of Decker’s imagination, but it’s a great story.

20th Century: Oft-copied cultural kitsch and main attraction in the Louvre’s American Road Show

Copies of and tributes to the Mona Lisa had been made before the scheme, including by Raphael and other members of Leonardo’s studio. But never as many as were made in the century that followed the theft. With no copyright to slow it down, the Mona Lisa has been the hottest printed shower curtain and coffee mug item at the gift shop of every museum she’s ever visited, and many more that she hasn’t.

As President and Mrs. Kennedy appreciated the painting in Washington in 1962, Penny Arcade was a 13 year old New York runaway, at the beginning of a lesson about how the world treats women. By 1997, the well-seasoned performance artist had worked with Andy Warhol and in John Vacarro’s Theatre of the Ridiculous, and had a few things to say about the Mona Lisa, who has “No mouth, no cunt,” and, “stops at the waist.”

UPDATE: Penny got back to us! It seems like she’s mellowed since Bad Reputation.

An insurance assessment done ahead of the 1962-63 US exhibition valued the Mona Lisa at US $100 million ($957,314,569 in 2022 dollars), still a record.

Mona Lisa’s Value, as assessed for insurance: $100 million

Nobody has ever cussed the Girl With a Pearl Earring out to make an anti-social, counter-cultural feminist statement, and nobody’s ever thrown a cake at it either.

May 31, 2022, with protective glass well-creamed for unknown reasons

Details about the May 31 pastry-wielding attacker are thin at this time. A statement made by the cream slinger while the shot was still wet on the glass about the harm humans are causing to the planet casts him as an environmental activist of some kind, but we have our doubts. Any serious eco-terrorist would have been more deliberate about it, called out Chevron or something. This seems like noise made for the sake of it, or possibly as a diversion. Has the Louvre done an inventory lately?

Mona Lisa’s Value: unchanged

The messy smear of cream on her glass does not affect Mona Lisa’s value at all. In 2022, the painting is too famous and too unobtainable for this action to change anything beyond the Wikipedia footnotes. For anything to have an effect on something with that much gravity, it has to have built up a fair amount of gravity itself.

2010s: The Salvator Mundi and the Saudi Crown Affair

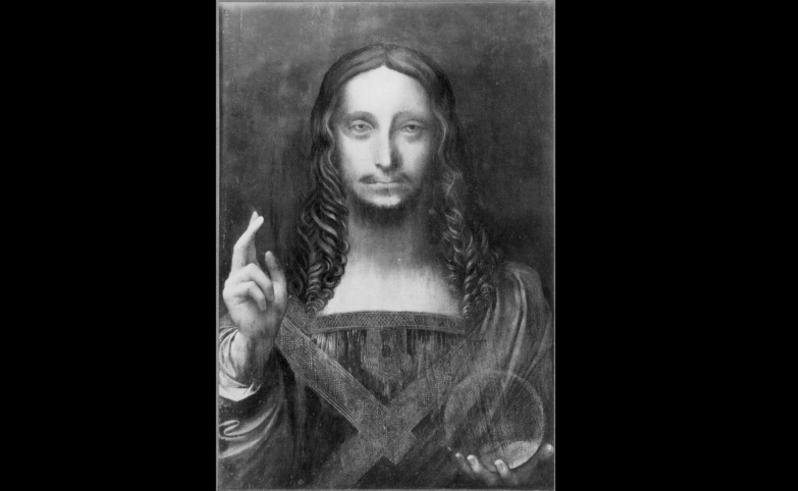

In 2014, Christie’s auction house handled the record-breaking sale of “Salvator Mundi” to the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism, with backing from Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Prince Mohammad Bin Salman for $450.3 million.

The painting is of Christ The Saviour holding an orb in his left hand and making a blessing gesture with his right. It had undergone extensive restoration since being bought in a New Orleans art auction in 2005 for $1,175. The buyers took it to an expert restorer who stripped off a great deal of overpainting to expose the base layer on the heavily damaged walnut panel.

The non-aesthetic difference between overpainting that was stripped off as part of the restoration and the overpainting applied as part of the restoration is not clear to this author. At any rate, as the restoration process proceeded into its later stages, the painting’s owners started to bring in various types of experts on Renaissance art from various galleries and universities to examine the work and asked them, in very hushed tones, if it was in fact what its handlers strongly suspected: an actual, autograph, hand-of-the-master Leonardo?

The appraisers were brought in in small groups that made them all feel like they were one of a very few, being asked a very delicate question. “We know this borders on the absurd, so we’d appreciate you keeping this on the down low so it doesn’t get around but… could it be?”

And what kind of (self-) important art expert wants to be brought in as part of an elite team that discovers something isn’t a Leonardo? Anyone could do that. And not just any Leonardo, it’s the LOST Leonardo! Re-discovered! Thanks to THEM, and the art history degree that their parents said would never amount to anything!

“Lost Leonardos” are all over the place in the realm of the potential. Kind of like gold mines. There are contenders turning up every now and again in Swiss bank vaults and private collections. Some are taken more seriously than others, and they aren’t often put up for sale. But Salvator Mundi was walked into the realm of the actual in a way that carefully gave everyone exactly what they wanted: The genuine article. The dream come alive.

It was sold to a Swiss art dealer in 2013 for $75 million, who immediately flipped it to Russian Oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev for $127.5 million. An expertly marketed 2017 exhibition tour through Hong Kong, San Francisco and New York that set the stage for the 2017 Christie’s sale had them lining up for hours just to get a look at it… just to experience it!

2017: Elite-tier fine art kingmaker

The Prince and the Emirs had reportedly intended for the Salvator Mundi to be the centerpiece of the UAE’s very own literal Louvre, the Louvre Abu Dhabi. The museum was built in 2012, and scheduled to open in 2017, using the name “Louvre” in a licensing deal with the Louvre proper.

The destination gallery is meant to bring the United Arab Emirates the type of international respect as a center of art and culture that is currently enjoyed by Paris, New York, and Amsterdam. The painting has yet to be hung in the Louvre Abu Dhabi, but was scheduled to be displayed in the Paris Louvre as part of a 2019 exhibition of 11 Leonardo works on the 500th anniversary of his birth. It was all set up, ready to open, with the programs printed and everything, when the Salvator Mundi’s owners pulled it from the exhibition at the last moment.

According to unnamed sources in The New York Times, the idea of having it displayed in the original Louvre was that it could be placed next to the original Mona Lisa, further solidifying its reputation as an original. A detailed forensic analysis of Salvator Mundi, and an official opinion of authenticity conducted by the Louvre ahead of the planned exhibition wasn’t good enough. Any analysis is bound to include “maybes” and “might haves.” The Emirs wanted the de facto approval that comes from prominence.

Perhaps concerned that allowing the Mona Lisa to be used in an obvious art laundering would affect its value, the Louvre reportedly balked at the placement demand, and the Royals walked with their painting. No official reason was given for the painting being pulled from the Paris Louvre, or not being hung in the Abu Dhabi Louvre. Other Times sources suggest the investors never intended to allow it to be displayed, and were only trying to create a build up for their own unveiling, which has yet to occur. Its whereabouts are presently unknown.

Mona Lisa’s Value: The ability to make or break empires of culture

A cloak and dagger power clash between the top of the art world and a monarchy, complete with mystery locations and sudden moves might be as good as a heist for a painting’s profile, but as a value play for art that already carries the record sale price, it seems kind of tacky.

The Emirati and Saudi Royals are right to be concerned about perceptions of the painting’s authenticity; if they paid $450 million for a marketing campaign, then hung it, the Louvre 2.0 would look bush league, and they’d look like saps. But the Kingdoms may have overplayed their hand. Exhibition alongside ten other Leonardos surely would have added to the Salvator Mudi’s patina of authenticity. The Louvre Abu Dhabi could have spent a few decades building its collection up, then tried for a Mona-Lisa-adjacent curation again. But it isn’t what they wanted.

Bloomberg reported in 2019 that Salvador Mundi was being kept on Prince Salman’s yacht, where it isn’t likely to encounter anyone inclined to give it a sidelong look with a skeptical half-smirk that says: “A Leonardo? I dunno…”

Readers interested in the Salvator Mudi Saga may enjoy the 2021 documentary The Lost Leonardo, or the acclaimed Micheal Lewis podcast Against The Rules.

Information for this briefing was found via the Associated Press and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.