Toronto-based concept software company Killi (TSXV: MYID) was the number one trader by volume on the TSX Venture this past Tuesday, doing 18.7 million shares worth of volume on its way to a +382% jump to close at $0.235. It followed up with a 5 million share Wednesday as it tried to find its level, closing down $-0.06 at $0.175, inviting our investigation of this curious tech company that, before Tuesday, had averaged 215,000 shares of volume per day at $0.057.

The company bills itself as a “privacy compliant identity ecosystem,” that enables its users to cash in on the data created by their personal browsing habits and consumer actions. It isn’t a new concept, but Killi’s more liquid approach and a changing data market landscape appears to be making it relevant.

The world of data brokerage operated for most of the internet era as an opaque layer that remained poorly understood by design, and whose polling numbers among those who knew it existed were very low. Data brokers would track the habits and interactions of consumers, then effectively sell the profiles to advertisers and sales people engaged in the great righteous evangelism of capitalism: sales.

Three of the four largest and most powerful companies in this economy: Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) and Google (NASDAQ:GOOG) are centered around the buying and selling of data. The very largest company, and the only one whose business centers around selling consumer products of their own design, Apple, is currently running ads that tout their products as data privacy solutions.

The individual’s desire to keep their digital footprint private isn’t new, but laws governing the conditions around which the entities who collect it can put it to use are. A tangle of state, local and federal digital privacy laws have tried to give users some kind of control in recent years, but between resistance from tech giants with lobby money and the lost cause of jurisdictionally limited lawmakers trying to set the rules for a borderless, etheral entity, the laws haven’t been able to give the users much in any practical sense. Many jurisdictions require companies to furnish users with the data they’ve collected upon request, but a list of personal google searches or grocery bills doesn’t hold much utility for an individual.

The laws have been successful, for the most part, at requiring user consent for the collector of the data to then re-sell that data. To hear Killi’s founding tech-bro Neil Sweeny tell it, that’s where Killi is going to make itself an indispensable layer of one of the largest transactional ecosystems in the world, ending the tyrannical reign of the data vampires and bringing value back to the people as it goes. But, first, it needs to establish a working system and foster its adoption.

Large number of users sign up to get paid a small amount of money.

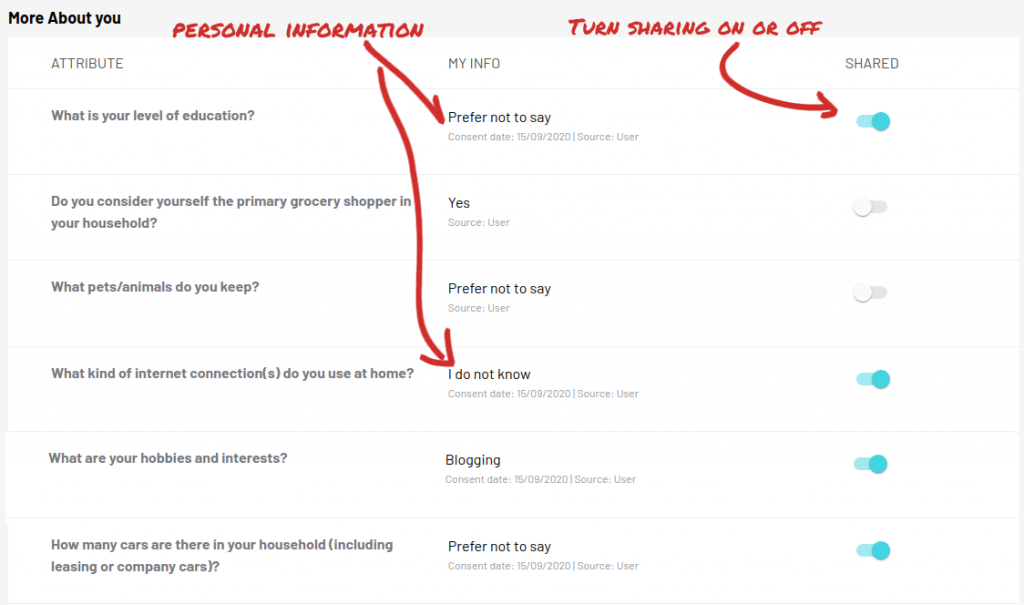

Killi’s sudden relevance follows a press release and an investor Zoom call in which the company announced that it had signed up 25 million users in September, five times the 4.8 million accounts it had created in August. Those accounts and the ones that came before it are invited to give Killi access to their phone’s GPS to collect location data, debit/credit card to collect purchasing / shopping data, and to hand over various personal data points (age, income, occupation, etc.).

Killi is gaining an edge on the data collectors who offer discounts or rewards for filling out surveys by instead offering its users actual money, paid weekly. The base survey earns the user one (1) dollar, and we suspect that if sustained use amounted to any substantial amount of money, the company would be leading with that potential instead of the “every little bit helps in this economy!” messaging that they’re going with. At least it’s honest.

But Killi doesn’t have to fling around big payments to become successful, it has to grow its user base and retain its users. Weekly checks are a good way to keep people around, and personal data ecosystems are rich environments for products that get users excited enough to evangelize.

If, for example, users could keep and own the music profile that Spotify builds around the songs they play and the songs they skip, they would have the ability to jump to a competitor with better sound quality or a bigger catalog, costs less, etc., without losing their playlists and listening profiles. A person who buys a new car every year sure doesn’t care about a few dollars a week in data residuals, but would surely be pleased to learn what dealers would do to get their attention.

Killi doesn’t presently have any income of significance. But its success hinging to some extent on it generating a profile for itself gives the equity the potential to gather the sustained retail buying that keeps it on the charts. The data resale market that it’s trying to address might be one of the largest commodity markets in the world, and the concept of sucking up a meaningful portion of it by giving the data producers a stake is a compelling one.

Information for this briefing was found via Sedar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to the organizations discussed. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.