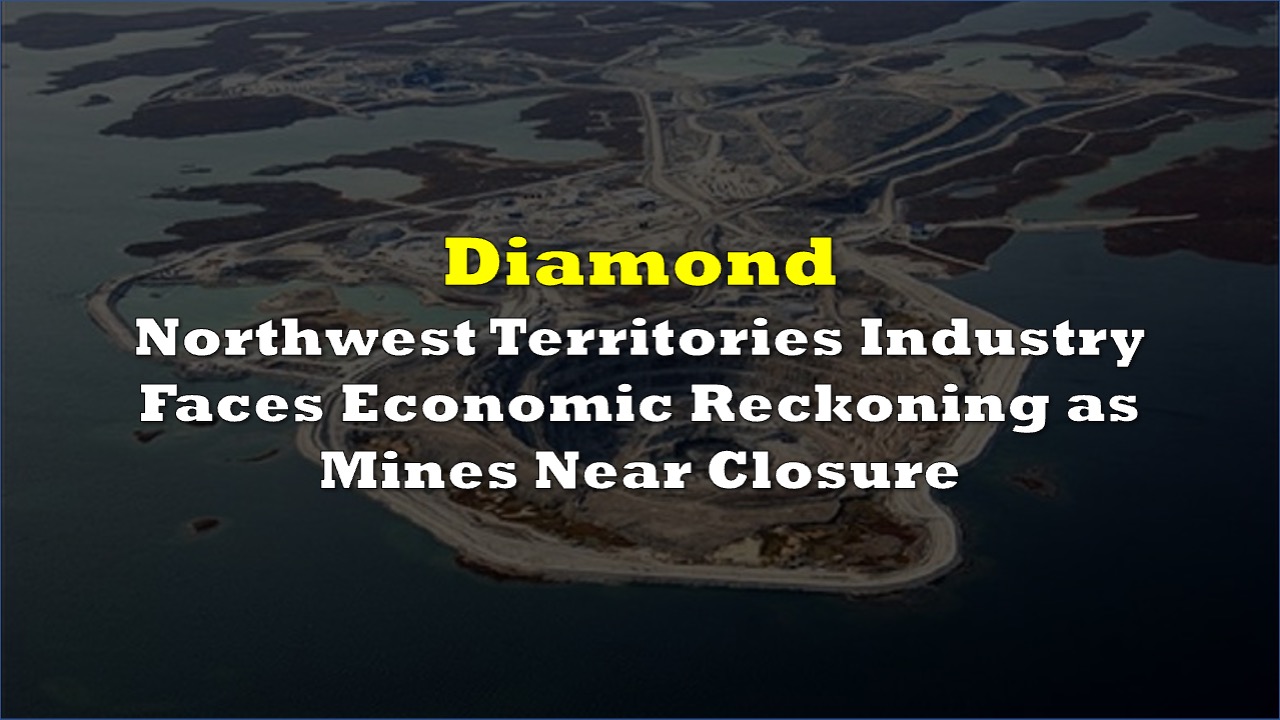

The Northwest Territories confronts a stark economic transition as its diamond mining industry, which generated $30 billion for the Canadian economy over 25 years, approaches its twilight.

Rio Tinto (ASX: RIO) plans to close its Diavik mine in March 2026 after exhausting ore reserves. The Gahcho Kue mine, operated by De Beers Canada and Mountain Province Diamonds, will continue production until 2031. The closures threaten more than 1,500 jobs in a territory of 46,000 residents, where diamond mining accounts for one-fifth of gross domestic product.

“Diamond mining in the Northwest Territories has been incredibly pivotal to our economy over the last 25 years,” Caitlin Cleveland, the territory’s minister of industry, tourism, and investment, said in an interview. The sector kept $20 billion of its $30 billion economic contribution within territorial borders.

Lab-grown diamonds have undercut natural stone prices, with the International Diamond Exchange’s price index falling sharply since early 2022. US President Donald Trump’s 50% tariffs on polished diamonds — most natural stones go to India for cutting before entering American markets — further squeeze profit margins.

Burgundy Diamond Mines‘ Ekati mine secured a $115 million federal loan in December to maintain operations amid what the company called “ongoing challenging market conditions.” Burgundy suspended its Australian Stock Exchange listing in September while seeking additional financing.

Paul Gruner, CEO of Tlicho Investment Corp., works with Rio Tinto to extend employment during Diavik’s closure and remediation phases. “Mines aren’t forever,” he said. “They are finite resources.” Reclamation work will sustain jobs for roughly three years before employment vanishes.

Diamond mine contracts generate 54% of total gross output for the territory’s four Indigenous development corporations, according to their 2024 report.

Population decline poses cascading risks, Gruner warned. Federal transfer payments calculate funding based on population counts, so resident departures would shrink territorial revenue while the public sector, a major employer, contracts. “It becomes a bit of that death spiral,” he said.

Heather Exner-Pirot, senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, noted that mine closure and rehabilitation will create “big business” for several years. “But those are not things that produce royalties and taxes,” she said.

Nice to be quoted alongside my friend Paul Gruner of the Tlicho Investment Corp on this story about the sunsetting NWT diamond industry.

— Heather Exner-Pirot (@ExnerPirot) January 1, 2026

Suffice to say Paul and I are more concerned about the economic implications than the NWT government.https://t.co/mgPRQZdH2V

Finance Minister Caroline Wawzonek said diamond revenues comprise most of the territory’s own-source income. Federal funding prevents an immediate fiscal crisis, but economic deterioration remains the primary concern.

Territorial leaders target critical minerals as a long-term replacement industry. Cleveland said the Northwest Territories holds nearly three-quarters of resources on Canada’s critical minerals list. The shift would require multiple smaller operations rather than the three large diamond producers that dominated the economy.

New mining development demands substantial infrastructure investment. Current roads serving diamond operations function only during winter months. The territory also depends heavily on diesel generation for power.

The federal government designated the Arctic Economic and Security Corridor — encompassing ports, all-season roads, runways, and communications systems across Nunavut and the Northwest Territories — as a potential nation-building project for expedited review.

Exner-Pirot questioned the wisdom of massive infrastructure spending before securing critical mineral investment commitments. “If you don’t have the private sector using this kind of infrastructure, it can become a real drag on the territorial economy,” she said. The territory lacks the tax base to maintain hundreds of kilometers of roads or transmission lines without industrial users.

Critical mineral prices would need to rise substantially to make Northwest Territories deposits commercially attractive, Exner-Pirot said. “There’s nothing on deck that would replace or even come close to replacing what the impact of the diamond mining sector was.”

Information for this story was found via the sources and companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to the organizations discussed. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.