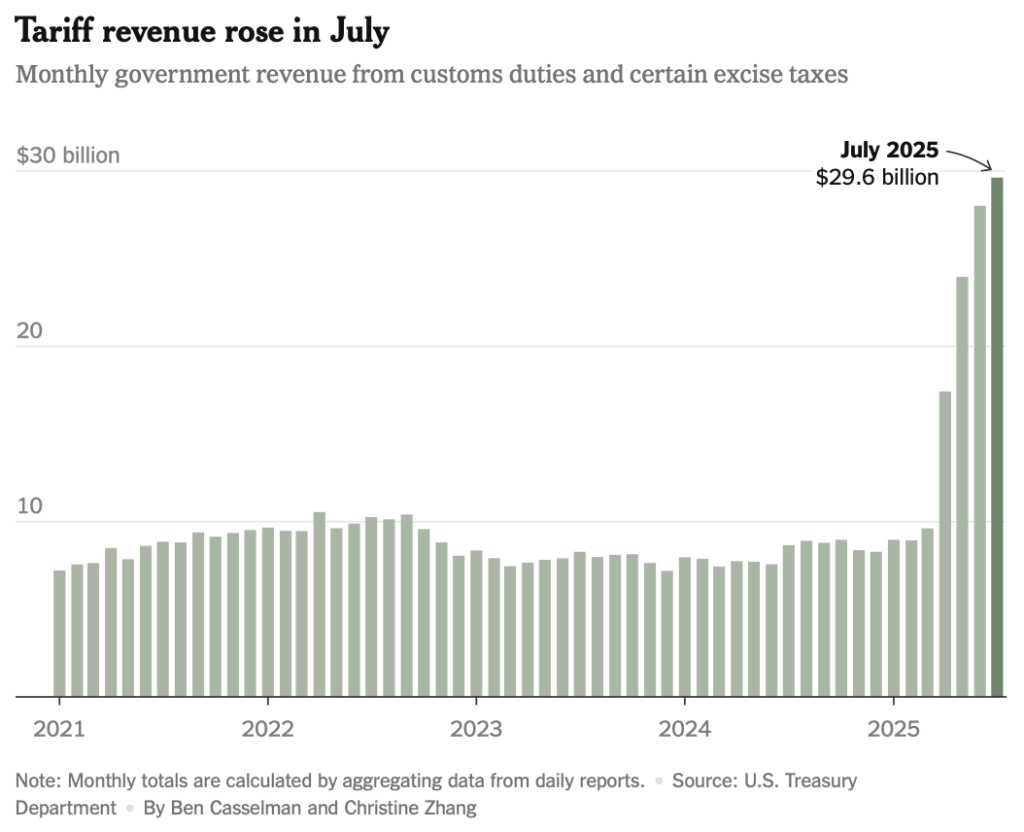

Tariffs are reshaping America’s balance sheet, but the cash pipeline seems to start and end at home.

Gross customs duties hit a record $29.6 billion in July, up from $27.2 billion in June, yielding $113.3 billion for the first nine months of fiscal 2025, almost double last year’s haul. Treasury officials say collections could reach $300 billion by December if higher “reciprocal” rates stick, putting tariffs behind only individual and payroll taxes as Washington’s fourth-largest income line.

The figures from Treasury’s daily statements show roughly $152 billion collected through July—already well above the full-year 2024 total. Average tariff rates have risen to 15.6%, with fresh 50% levies on Brazilian copper and 35% duties on Canadian goods expected starting August.

Who pays for the tariffs?

In theory, it’s the US importer. When a shipment clears customs, the American buyer wires the duty to the Treasury. So, if that is the only side of the equation we are looking at, President Donald Trump’s claim that “Tariffs are bringing Billions of Dollars into the USA!” is accurate on cash flow.

However, most of that cost flows downstream. Retailers such as Walmart can ask suppliers for discounts or absorb some margin pain, but they usually pass the increase along the chain. A 2019 Columbia-Princeton–New York Fed study found households absorbed nearly the entire burden—about $419 a year at the 2018 rate.

Later work suggests today’s rates push the hit above $800 per family.

Lower income Americans spend a bigger share of earnings on goods now subject to duties, while the 2024 income tax cuts favored higher earners. Tariffs therefore shift the tax mix from wages to consumption.

The quality of tariffs is strained

Economists estimate the tariff regime could shave up to 1% of GDP and raise long run inflation, eroding part of the nominal windfall. Exporters abroad are shifting markets—for instance, Brazilian coffee producers are pivoting to China after a 50% US duty—while US manufacturers report higher input costs and delayed investment.

Tariffs now deliver roughly 5% of federal receipts, up from 2% historically. If rates and import volumes hold, Tax Foundation modeling suggests $2.2 trillion could flow to Washington over the next decade.

Yet every dollar relies on consumers paying more, firms absorbing margin hits, or supply chains relocating—none pain-free.

Can we scrap the tariffs?

It would not be easy especially if the revenue plans are already multiplying and politicians are already counting on the money.

“This is addictive,” warns Wharton economist Joao Gomes. “A source of revenue is very hard to turn away from when the debt and deficit are what they are.”

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent calls the customs boom proof the US is “reaping the rewards” of tariff policy. Trump has floated a consumer “dividend,” while Sen. Josh Hawley proposes $600 checks. Others eye the funds for deficit reduction or new social programs.

Tariffs are plugging budget holes and funding new promises, but the check is signed in America. Until policymakers quit the habit—or replace it with another tax—households remain the silent underwriters of Washington’s newest revenue stream.

Information for this briefing was found via The New York Times, Economic Times, and the sources and companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses