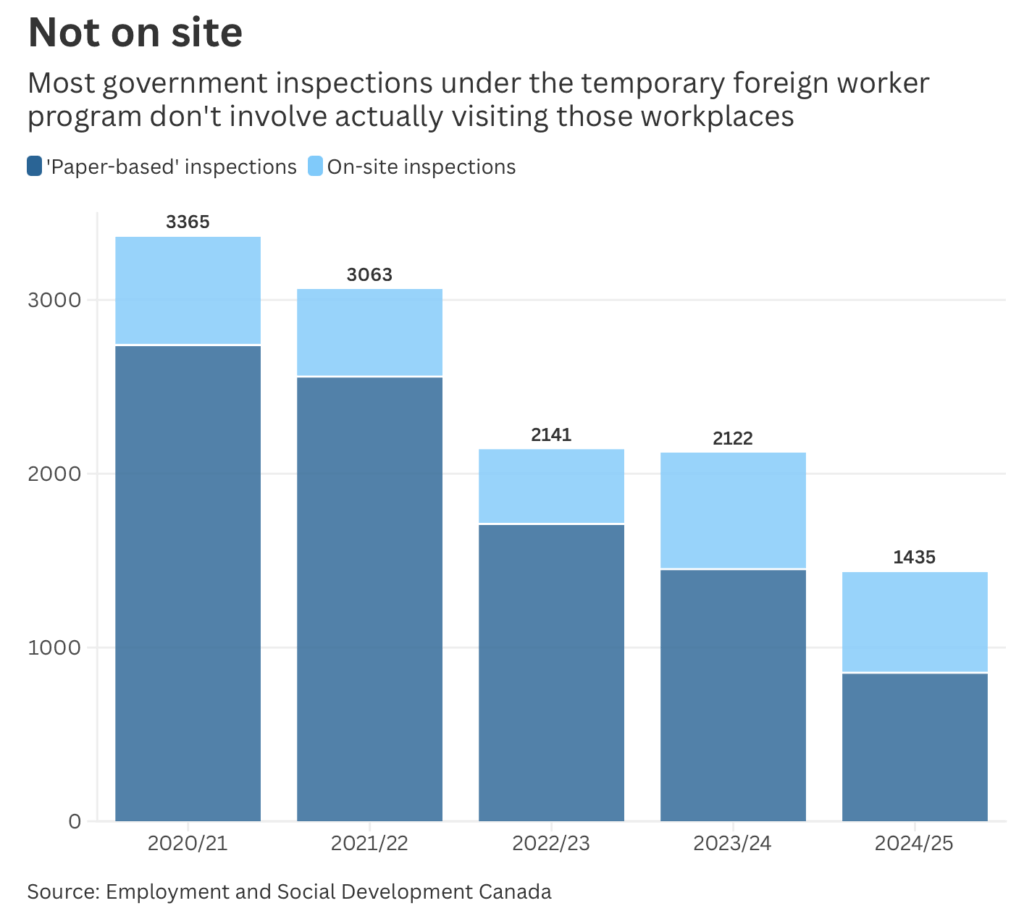

Canada’s labour enforcer conducted more than 12,000 temporary foreign worker inspections since 2020, and 77% of them involved no site visit at all, according to an investigative report.

Employment and Social Development Canada confirmed to the Investigative Journalism Foundation that most compliance checks under the program were “paper-based,” meaning interviews and document requests were done remotely rather than at the workplace.

The paper-based reviews coincided with annual inspection counts falling from 3,365 in 2020/21 to 1,435 in 2024/25, down 57%, its largest drop since the pandemic.

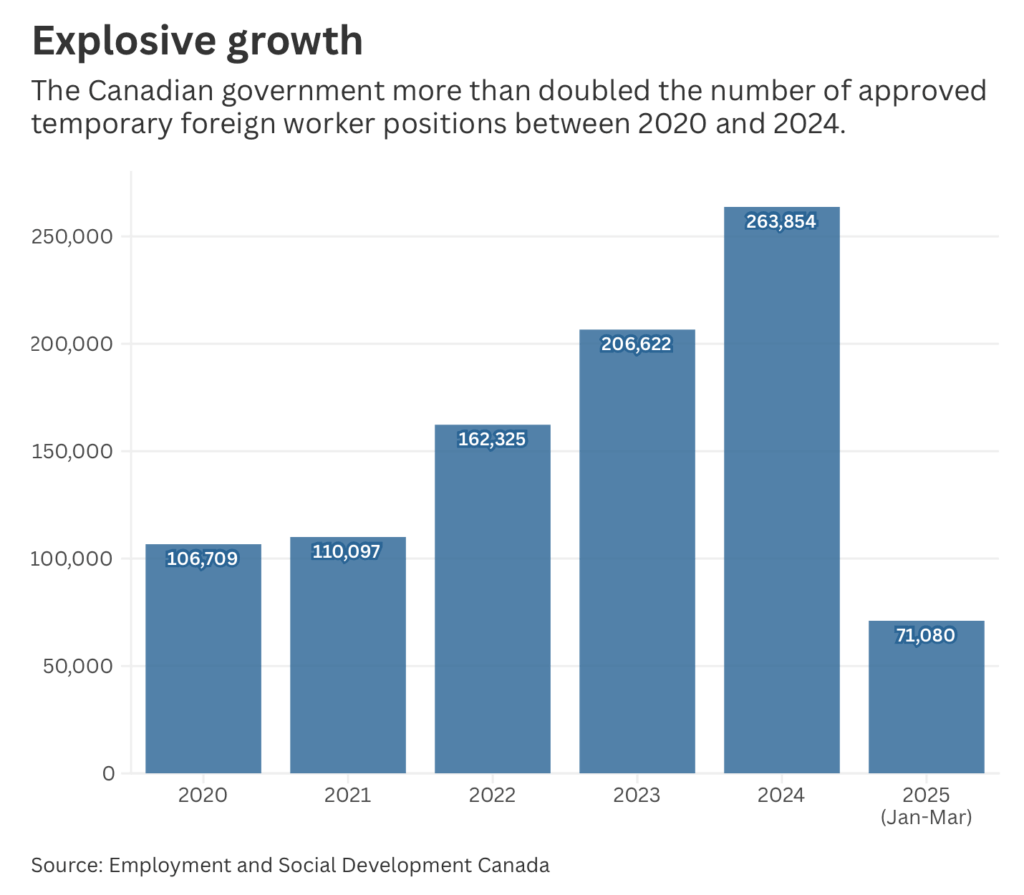

At the same time, Ottawa approved far more roles for foreign hires. ESDC data show TFW positions rose from 206,622 in 2023 to 263,854 in 2024. The latter is also a 147% increase versus 2020.

In addition, in the first quarter of 2025 alone, approvals reached 71,080.

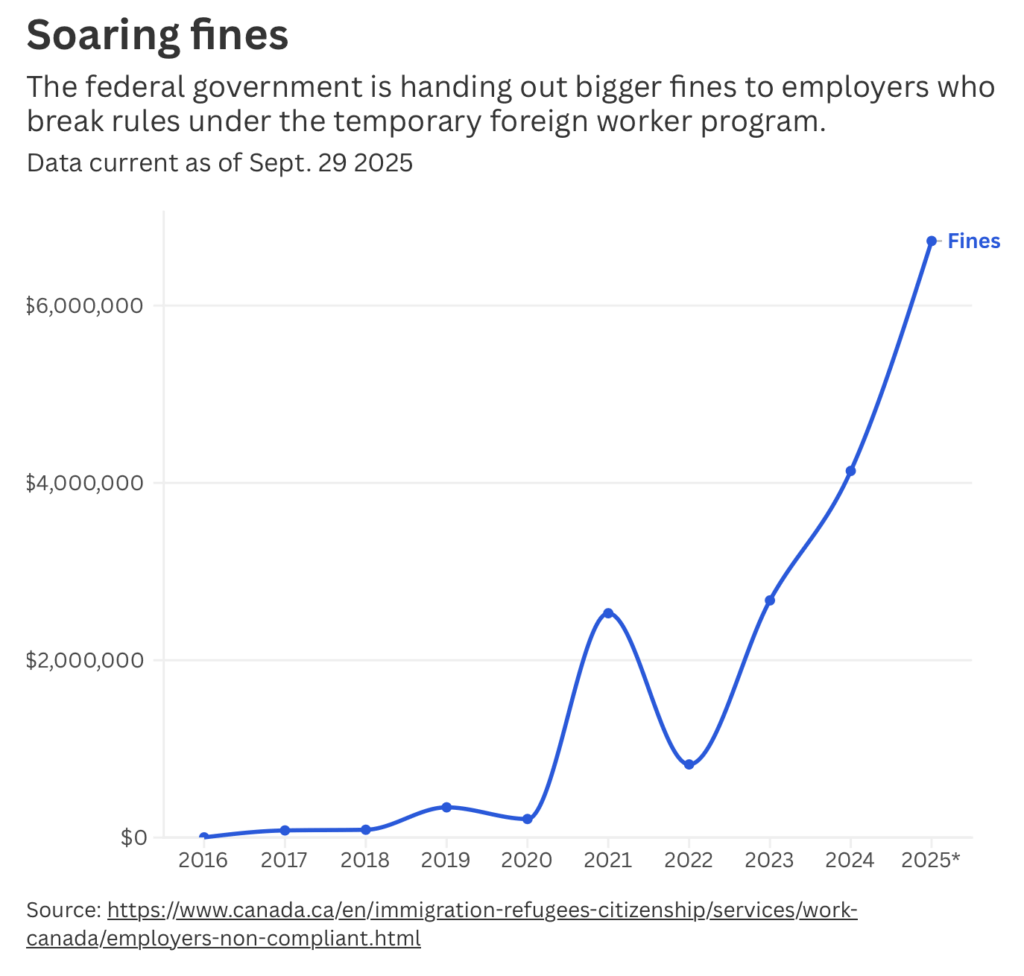

ESDC defends that the paper reviews are “thorough” and that enforcement has been toughened. Between January and September 2025, the department levied more than $6.7 million in fines, already surpassing 2024’s record. Spokesperson Mila Roy said the rise in penalties is “not a sign of widespread abuse” but reflects stronger enforcement and accountability.

The government’s own penalty registry shows most fines from 2020–2025 were issued for failing to provide requested records, not directly for abuse or housing violations. Advocates say that pattern underscores the limits of remote checks.

“When we’re talking about workers who are facing really terrible conditions at work or with their accommodations, as most farmworkers are, these paper-based inspections are useless,” said Amanda Aziz, staff lawyer at the Migrant Workers Centre in Vancouver.

Workers describe how leverage in the system can be abused. Raul, a Mexican carpenter recruited to Metro Vancouver in 2022, told the IJF he was asked to pay nearly $12,000 in fees tied to his job and later faced out-of-pocket tool costs, unpaid mandatory meetings, and termination five months into a two-year contract. He ultimately obtained an abuse-open work permit which afforded him to stay in the country.

Field organizers report what remote audits miss on farms, the largest TFW employer. “They live in fear, and I can feel that,” said Byron Cruz, who has visited hundreds of B.C. farms over more than a decade. He said cramped, unsanitary housing is common and language barriers make it difficult for workers—often from Mexico or Guatemala—to communicate with inspectors even when visits occur. “If it’s on paper, the employer is going to tell the government everything they want to hear,” Cruz said.

Independent reviews have echoed those concerns. A Deloitte report commissioned by Ottawa found evidence some employers coerced money or labour by leveraging the value of the Labour Market Impact Assessment: “Examples indicate employers are aware of the value placed on the LMIA… and use this as leverage to exploit [temporary foreign workers],” urging more randomized, field-level reviews.

A UN special rapporteur previously likened aspects of the program to a “contemporary form of slavery.”

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre and BC Premier David Eby have each proposed abolishing or overhauling the program, citing concerns from youth unemployment to rising shelter use.

Aziz argues reforms should focus on worker protection rather than scapegoating migrants: decouple visas from a single employer, expand unannounced, in-person inspections, and ensure workers can safely report problems.

Ottawa said in January it would target “high-risk” sectors and has raised penalties, but it is expected that the inspection mix remains overwhelmingly paper-based while program scale keeps growing.

Information for this story was found via the sources and companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to the organizations discussed. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.

One Response

A tall order for us to pay while we deny 20 and 30 year old s job opportunities and housing to give the entire third world mobility. …….I’d say shameful but this country doesn’t have any!!!!