This story about IBM eliminating jobs with AI has been making a fair amount of noise in the echo chamber. The iterations are pretty loud and scary, even when they aren’t trying to be, like this one:

The Bloomberg story that appears to have started it all has International Business Machines Corp. (NYSE: IBM) CEO Arvind Krishna projecting that 30% of the company’s 26,000 back-office workers “could” be replaced by AI and automation, “over a five year period,” which is an interesting enough prospect from the standpoint of both business and labour to make it worth repeating. Let’s see about giving it some context.

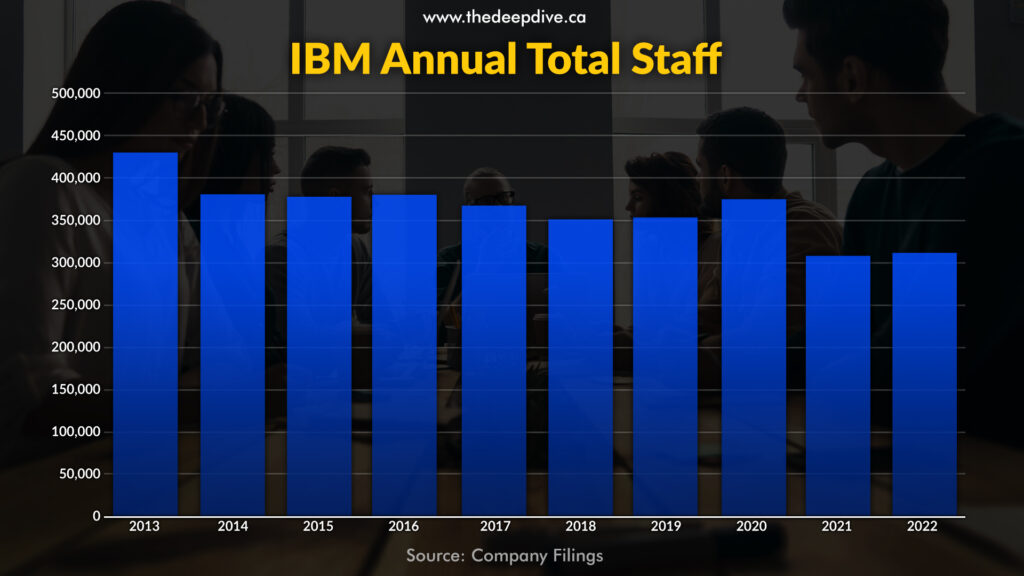

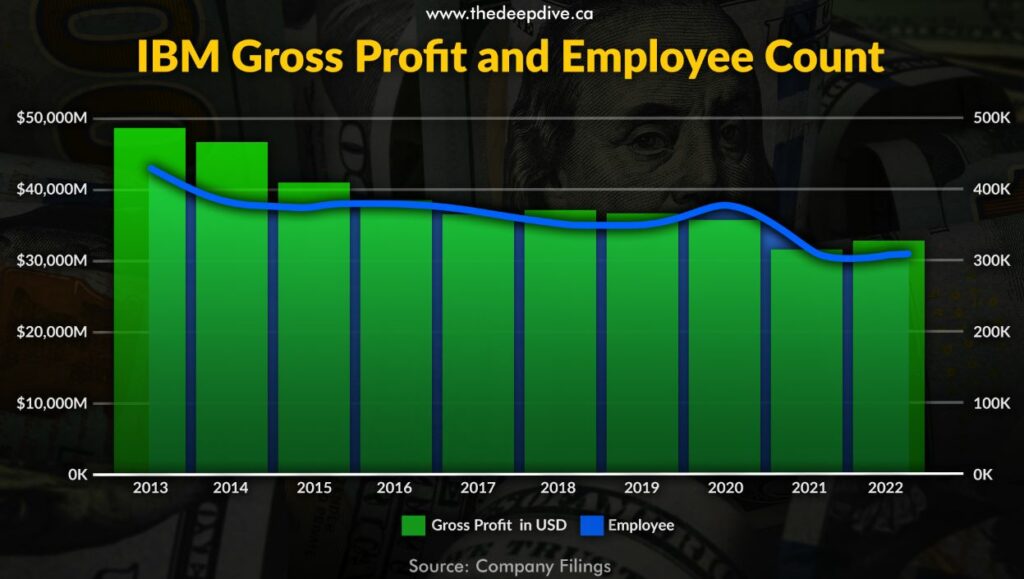

IBM had 311,000 employees at the end of 2022.

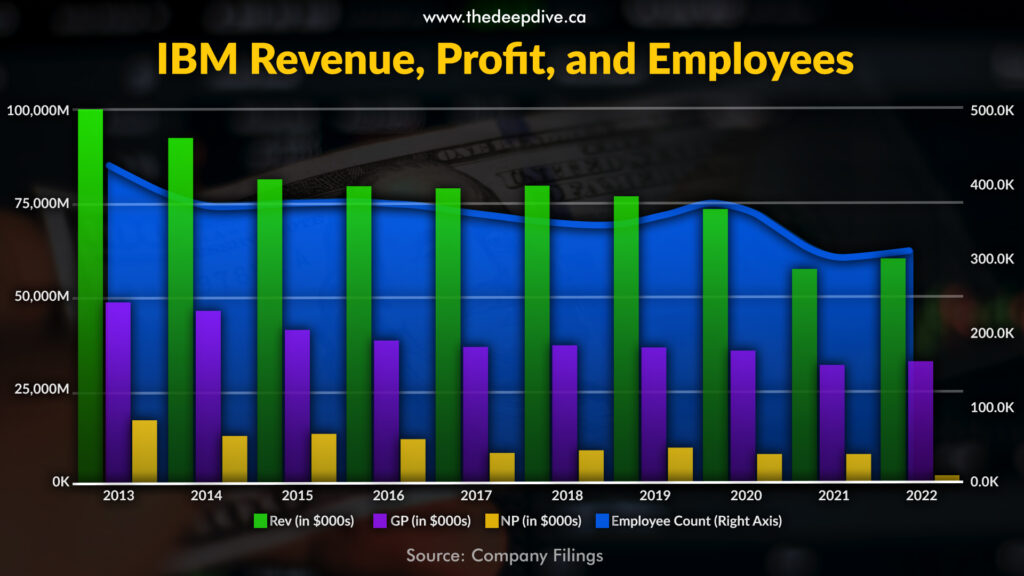

The IT giant’s labour pool has slid since 2013 at about the same pace as all of its top-line, bottom-line and cash flow metrics.

The stock has remained steady, and neither IBM nor its shareholders seem too worried about less money coming in the door. IBM always has a plan, and it’s used to executing its plan from a position of strength.

International Business Machines is an anachronism: a big-cap, blue-chip legacy industrial company that is a cutting-edge IT powerhouse. It’s been a relevant part of the American enterprise IT landscape since it was selling typewriters and punch card tabulators. It’s been through a personal computing boom, an internet boom, a smartphone boom, an exponential explosion of enterprise software that has grown trillions of dollars worth of competition around it and, without really being a leader in any of it, still hasn’t been knocked off its spot at the top of the American IT industry.

It’s one of four IT companies in the Dow (along with Cisco, Microsoft, and Salesforce), and the one that’s been there the longest by more than a decade. Its present stretch as a Dow component began in 1979, and its previous stretch began and ended in the 1930s (kicked out during WWII, because of the Nazi collaborator thing).

It’s a name the market can trust, so it can maintain relevance the old-fashioned way: by buying it.

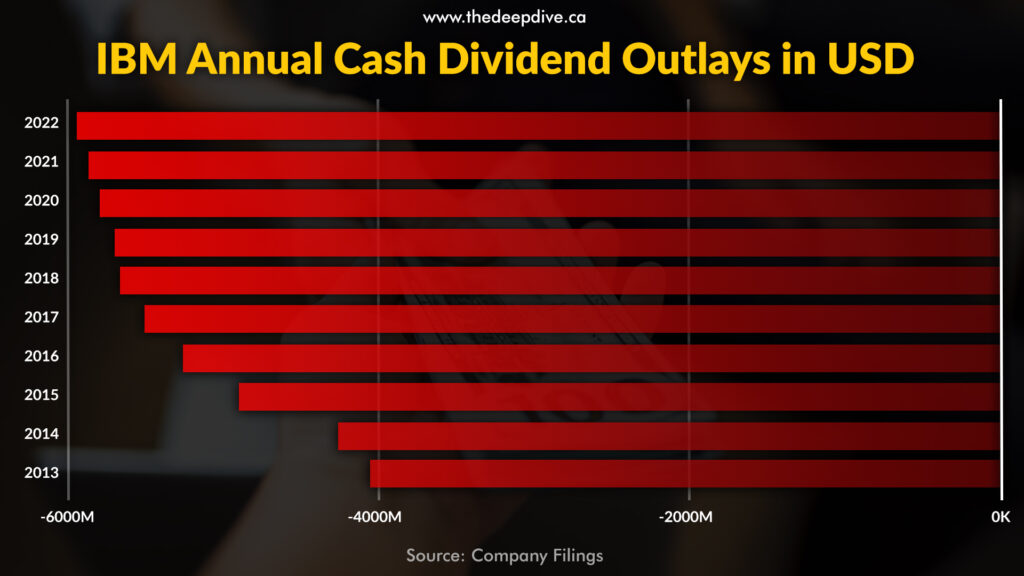

IBM achieves this capital consistency with a steady-Eddie dividend. The $1.66 / share quarterly dividend it paid in the first quarter of 2023 was up a penny from the $1.65 quarterly dividend it paid in 2022, which was up a penny from the one it paid in 2021, etc.

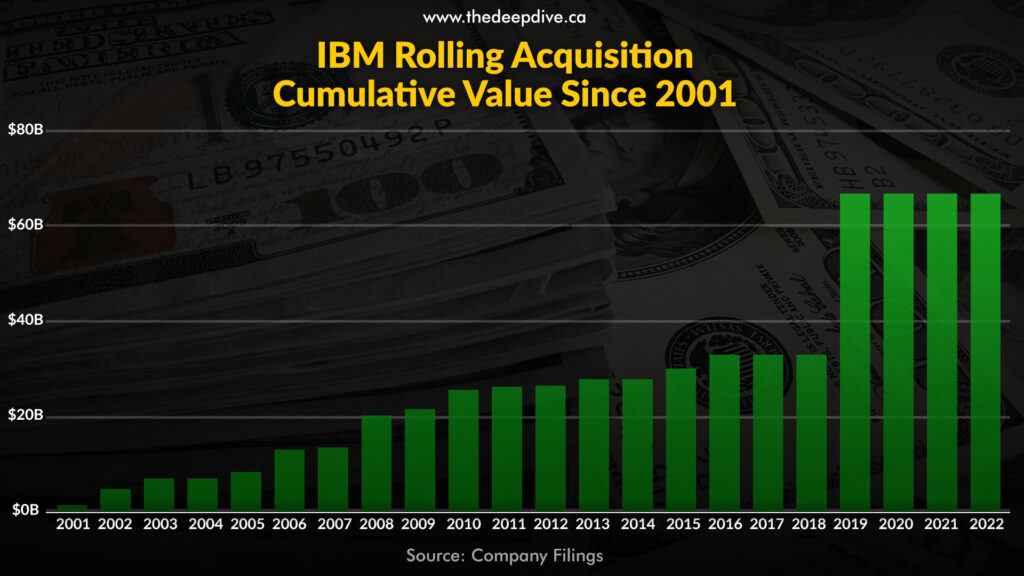

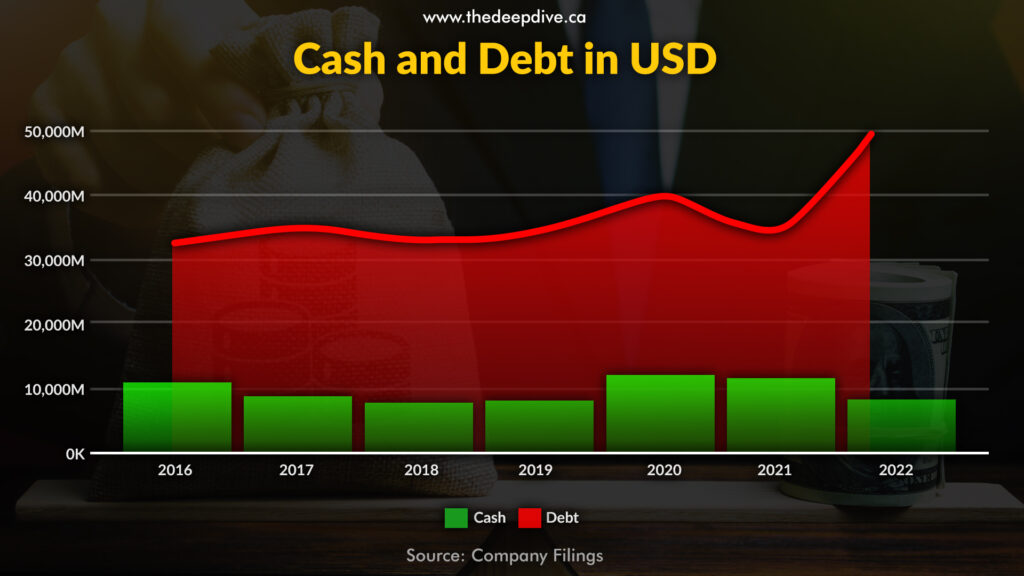

An informal tally has IBM making 187 acquisitions since 2001, and 96 since 2010. The value of most of them is undisclosed, but 36 of the 187 acquisitions that we do have values for total $66.8 billion (without adjusting for inflation). The sticker prices on 16 of the 96 IBM acquisitions that have happened since 2010 total $45.5 billion, $34 billion of which is their 2019 acquisition of Red Hat Inc.; its most expensive acquisition to date.

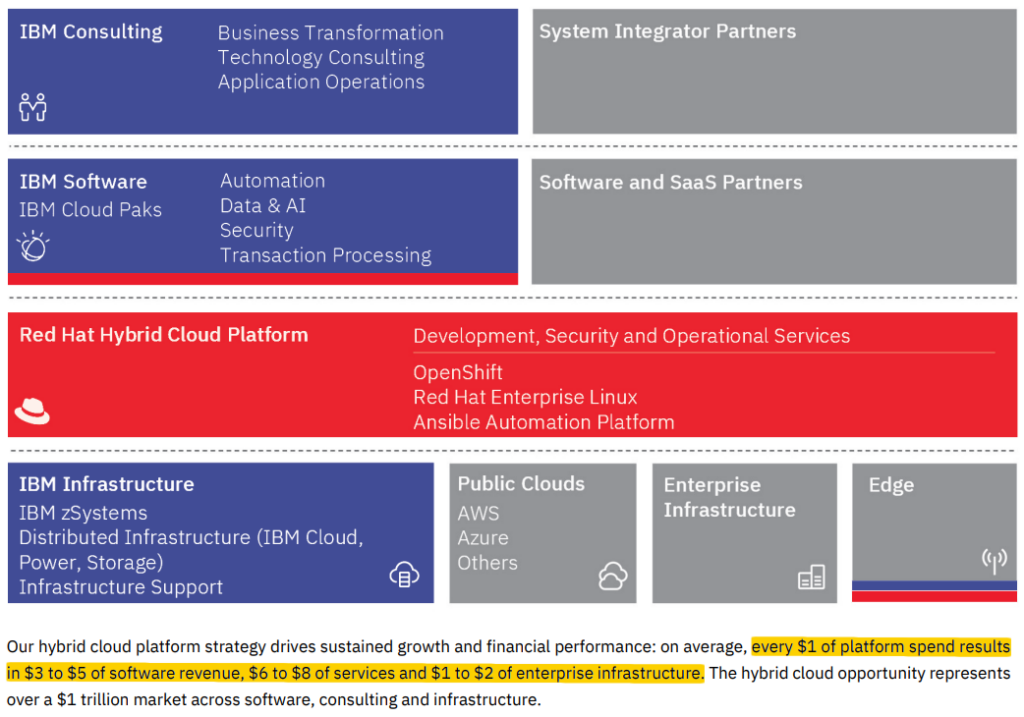

Red Hat is a purveyor of custom, open-source software solutions for enterprises. The modern IBM uses Red Hat as part of its consulting and software businesses, which accounted for more than 70% of its total revenue in 2022.

Most of what IBM does now consists of setting up systems for large to very-large enterprises that can afford modern, custom, hybrid-cloud systems of their very own and, from some perspective, can’t afford not to have one.

A business that has commissioned a corporate data environment from IBM can say that it’s addressed its cybersecurity risk, and is prepared to adjust to its industry as products and practices modernize. The core of IBM’s product offerings is container-based cloud-hosted infrastructure that keeps a client business ready to spin up and deploy whichever kind of software or system can help it, then pivot to something else or take off on a parallel track if necessary. Two years ago, the cloud-based containers of IBM clients might have been used to launch a crypto token or host a crypto payments system.

Tomorrow it could be anything. Today, it’s AI.

IBM is moving this software/middleware/hardware stack, and the consulting that puts it together, with the notion that AI growth is the future. It’s featured prominently in the company’s strategy atlas, because the possibility that it could become a significant part of the near-future landscape of American and global enterprises is a very real one.

If IBM was sure it could implement AI systems that cut back office staff by 30% over five years for itself or anyone else, it wouldn’t shout it at a Bloomberg reporter, it would just do it. Krishna is dreaming about it out loud to the press to telegraph to the companies who can afford it that IBM clients will be the ones taking advantage of such a development. The rate at which IBM can make AI a useful operational component will probably have a lot to do with how many companies it can talk into being early-adopter guinea pigs that help work out how it’s best deployed.

Cost of the Shift

Setting itself up as a modern modernizer has cost IBM revenue and earnings. It’s been able to keep the dividend up by using its cash and credit, and those things can only keep up for so long.

If the hybrid-cloud/AI strategy does work out, IBM probably won’t need less staff, overall, it will need more.

The company’s gross profit (revenue less cost of sales) and total employees have consistently marched in lockstep over the past 10 years and, surely, the world’s largest computer and data-analysis business realizes that.

The promise of new tech always gets attention. It makes labour interests worry about being replaced and makes capital interests excited about replacing labour and its cost.

We recall plagues of analysis-free headline and bullet point journalism like this breaking out around the advents of the personal computer and the internet, and they probably happened around the debuts of the steam engine and weaving loom, too. It’s the fear and greed talking, as usual.

It used to take a room full of accountants on abacuses and chalk boards a few months to put a company’s annual report together. Computers didn’t put all those accountants out on the street, they freed them up to do more useful and important work.

If and when applied AI systems are able to automate and replace certain back-office functions, it stands to reason that the people who used to do that work will move on to do other, more meaningful or valuable, and less monotonous work, improving the efficiency and reach of enterprises.

To date, the most obvious present-day application of AI technology just happens to be in The Dive‘s core business of news content publishing. An art which is also practiced, in some sense, by Gurgavin and an unknown number of other headline shouters.

We’re going to have a closer look at that in an upcoming episode.

Information for this story was found via company filings, and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to the organizations discussed. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.