SWIFT: the “Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications,” is being discussed by international powers and the media as a potential means of sanction against The Russian Federation, whose military advance into the Ukraine is testing the resolve of Western power nations by the day.

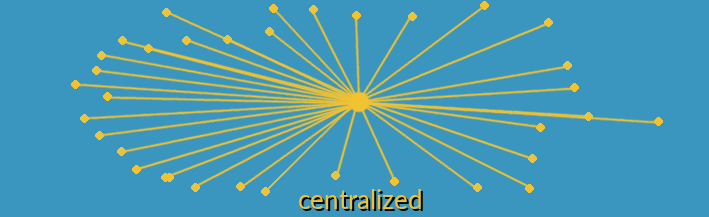

The SWIFT system was developed in Belgium in the 1970s to facilitate international and inter-bank money transfers. It was an age before personal computers, when everything was done by telex machine. Then, as now, for a bank to send money to another bank, it needed to have an account with that other bank; a banking relationship. But no bank in the world has an account with every other bank in the world, that would create too much paperwork.

As commerce went global, it became necessary to send money to a growing number of banks and institutions spread out further around the globe. The landscape became one that could be easily dominated by the large US banks that have banking relationships with the most other banks.

So, some Belgians developed a system of common standards by which bank transfer requests and payment confirmations could be made, and a secure network over which they could be sent. Common standards are the first step in any working information network. HTML is the common standard that web pages are built on. All browsers do the same basic thing with the code The Deep Dive sends to them, and display the same version of the site (materially) no matter what device they’re on or where it is on the network. The browser knows what to expect, and the server knows what to send, because there is an HTML common standard.

Prior to SWIFT, international payments were centralized around large US Banks. There was no reason to keep a settlement account with any other bank, because most banks’ networks weren’t that deep.

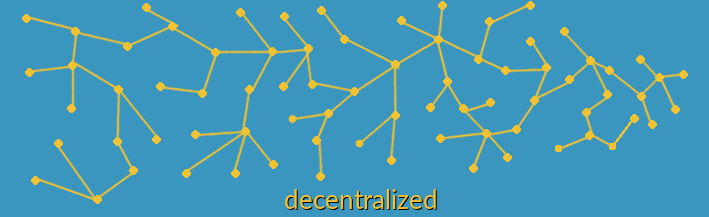

Once the SWIFT common standard had been established, the Belgian co-operative was able to build and operate a secure network over which the SWIFT “language” could be used to send transfer requests and payment receipts: the SWIFT network. The network doesn’t handle the money being transferred, it routes the messages between the banks that are making the transfers. Banks that don’t have accounts with one another still need to send transfers through middleman banks to get the money where it’s meant to go, but communicating through common standards on a secure network makes it easier for them to find and become transaction middlemen, and prevents any single financial monoliths from becoming payments clearinghouses and controlling global finance.

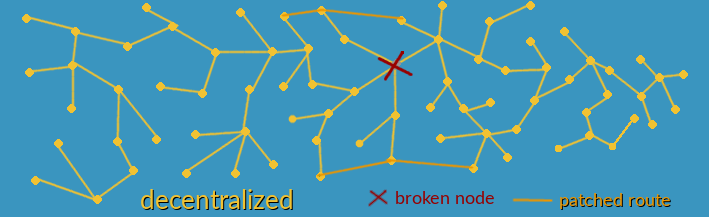

SWIFT allowed the global banking network to develop a natural decentralization. Big banks with a large number of inter-bank relationships are still important nodes forming backbones of sorts, but there are more available routes for money to skip its way across the network.

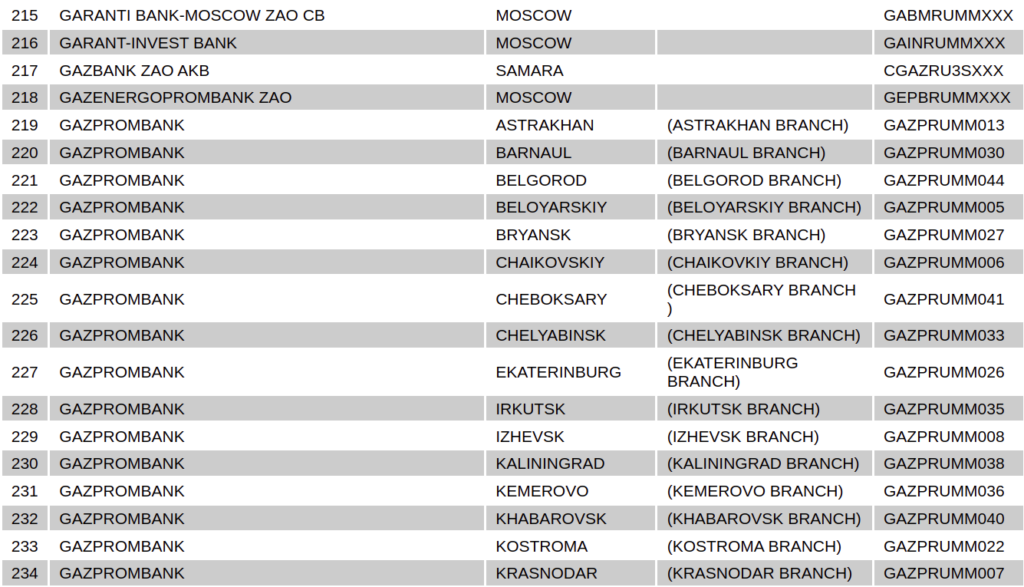

But a bank that isn’t on the network can’t use it to send or receive payments, and can’t facilitate payments either. There are 862 individual SWIFT codes of Russian origin, belonging to somewhere around 300 financial institutions. Removing those 300 banks from the 11,000 bank network wouldn’t leave a hole that the network itself can’t work around.

But it would prevent those banks from using the network to facilitate transfers. That means anyone who wants to send money to the Gazprombank St. Petersberg Branch to secure natural gas delivery is going to have to arrange for it outside of SWIFT. And chances are, they will.

Russia has already developed a SWIFT clone called SPFS. It is used mostly within Russia, but has been connected to 23 foreign banks as of 2020, and nothing is preventing it from welcoming more banks on board. Foreign banks linked in to both systems could also act as connecting hubs, making SPFS a functional extension of SWIFT.

A de-centralized network is more difficult to impede than a centralized one, but it isn’t impossible. If the US, EU and UK were committed, they could go after the bridge banks, and threaten to cut them out of SWIFT too, but that could get awkward if they balked. Any node that’s cut out of a working network creates a gap, and if the gap makes routing impossible on the network, the nodes trying to make the connection are bound to work on a way to make the connection off-network.

You knew it was coming.

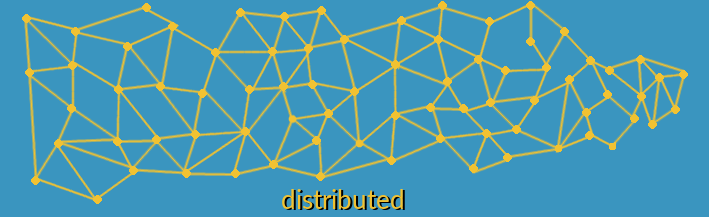

Distributed networks, like the ones formed by blockchains, are immutable. Every node is connected to every other node, by virtue of the fact that they’re all working on copies of the same ledger. If nine tenths of the miners processing the bitcoin ledger went down at the same time, the coins would continue to transfer between wallets, and there wouldn’t be anything anyone could do to stop it.

It isn’t practical for Russia to just start doing international petroleum commerce in bitcoin tomorrow, because cryptocurrencies are still highly volatile. But blockchain tech hadn’t even been invented yet when SWIFT was set up. In the decade or so since it’s become a household name, private banks and financial institutions have had time to look into it. None have developed their own cryptocurrencies or currencies-as-payment systems, presumably because there was no reason to.

Necessity is the mother (Russia) of invention

But nature abhors a vacuum. If Russia is given enough incentive to build out a blockchain-based international payments system, there’s no telling what it comes up with. The blockchain systems we have today are most beneficial to the entities that can create the most energy at the lowest cost, which sounds like it would suit Russia just fine.

The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.