“It’s an information-based economy,” the saying goes.

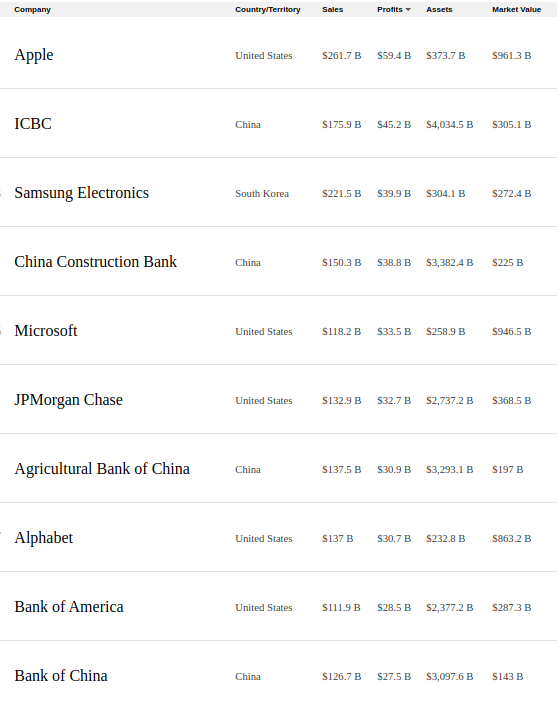

So much so that four of the top ten most profitable companies in the world are tech companies. Apple, Samsung, Alphabet and Microsoft all trade in information or otherwise sell a means of organizing and applying it. By that metric, info is more valuable to traffic in than oil (the most profitable oilco, Royal Dutch Shell, is #11). The other six in the top ten are all banks, because the only commodity in the same class as information is actual money.

This column is weary of organizations who actively try to keep information from those who seek it, either through obfuscation, inadequate reporting, or just good old-fashioned lying. There is a whole class of equities whose continued existence relies on the financial illiteracy of functional compulsive gamblers who tell themselves that their “trading” is somehow different than a trip to the track. Their (wilful?) illiteracy is an effective barrier to vital information that would surely sink various never-performing company if it made its way to the people they’re trying to fleece with any sort of context.

While it seems a marvel that blood-tech-based scam vehicle Theranos Inc. was able to rob investors of $700 million without showing any of those investors any financial statements (as first reported by Francine McKenna in MarketWatch), keeping the core message in the forefront and burying any objective measure of progress was surely central to the scam’s sustained “success.”

The wealthy, high-profile backers that Theranos conned, including the Clinton Foundation, Henry Kissinger and the Wallgreen family, must all have advisory teams who would have pulled the fire alarm if they ever got their nerdy little hands on a set of Theranos financial statements. But by keeping the marks dreaming on how much richer and better liked they were going to become for having backed the biggest medical technology breakthrough since Salk, Theranos had them handing over money every time the company needed it, and telling any numbers dork who said they should probably look at the statements first to shove it.

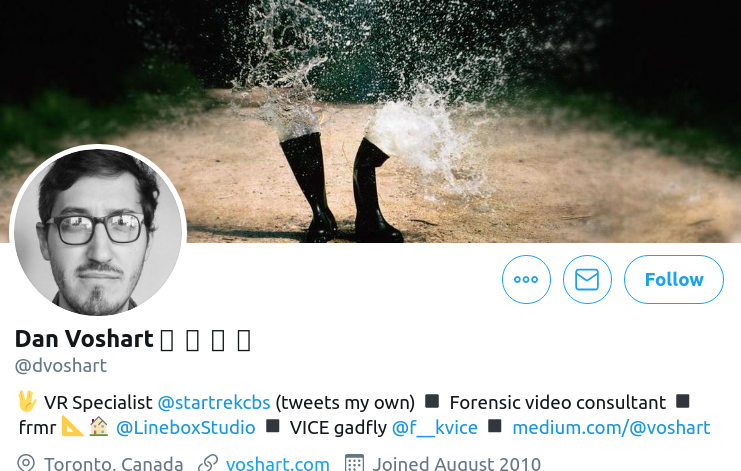

But regular people aren’t as easily fooled as the Davos set, and don’t have the tunnel vision of penny stock junkies. They get curious sometimes and start looking into how the sausage is made. This Daniel Voshart fellow, for example, who looks like a Toronto hipster (because he is a Toronto hipster, follow him on twitter), might as well be the prime demographic-based target for teched-out financial savings company Weathsimple, who have likely taken over the ad space in your favourite podcast as the country barrels towards the RRSP contribution deadline. Wealthsimple markets a socially responsible investing (SRI) portfolio as a way for socially conscious young professionals to sleep well as their money grows backing companies that “meet a certain threshold of social responsibility.” They don’t say what that threshold is, but do say that the investments “take into consideration environmental impact as well as social and governance concerns.”

Voshart looked into it and was disappointed not to be able to download a list of the components of Wealthsimple’s SRI porfolio right from the website, and probably wasn’t surprised that after hunting them down through the individual ETFs that comprise this fund-of-funds in a marketable wrapper, that the “social responsible” portfolio is full of oil companies, tobacco companies, and most of the pipeline companies that he’d been trying to avoid with his investment choices.

Voshart photoshopped up a gif of Weathsimple CEO Mike Katchen hacking a dart in front of the Fort McMurray tar sands as his feature image, only to have a DMCA take-down notice filed by Weathsimple’s legal department, which makes us question their priorities at the least.

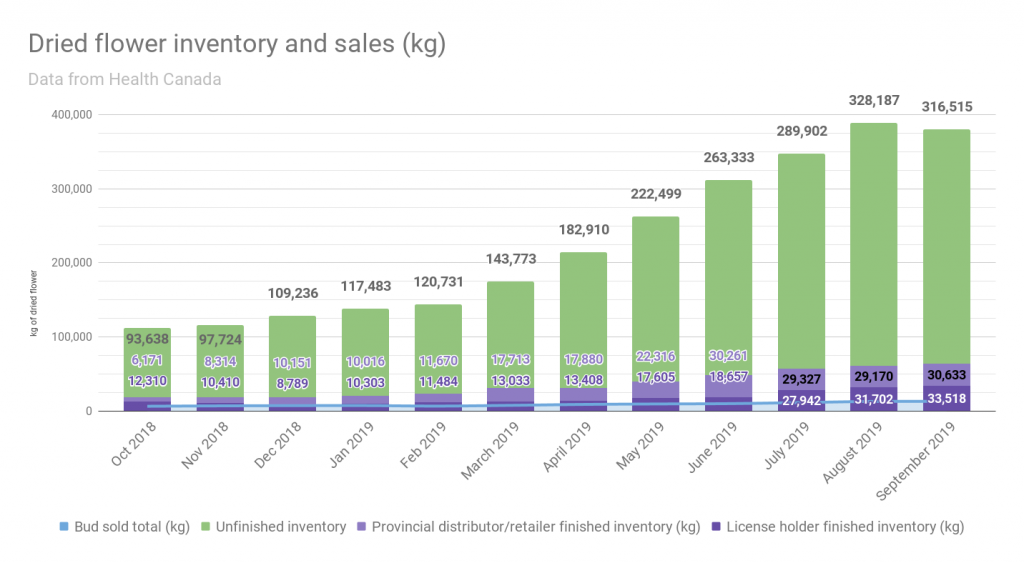

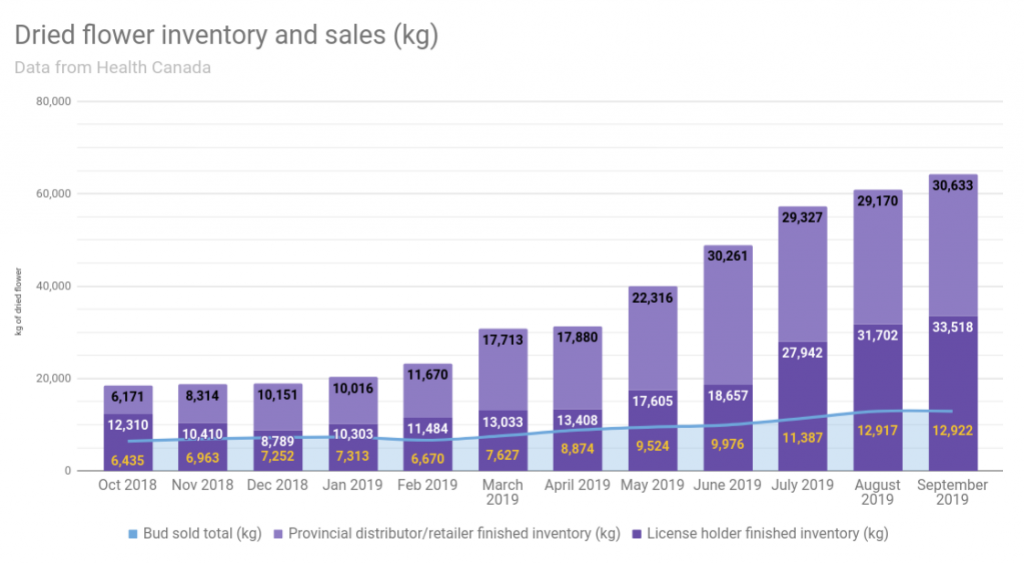

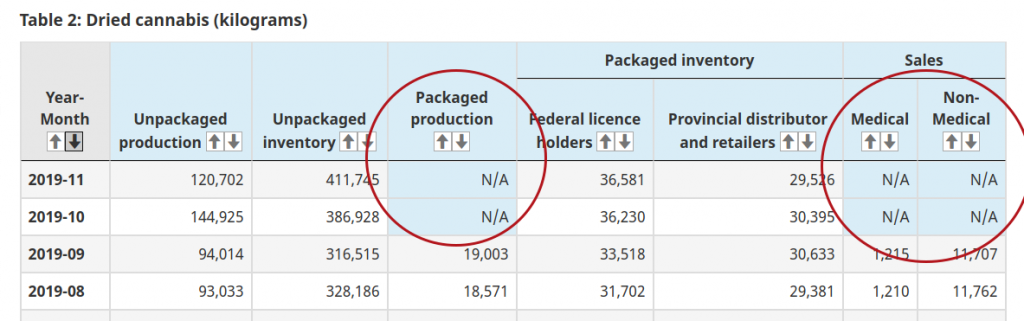

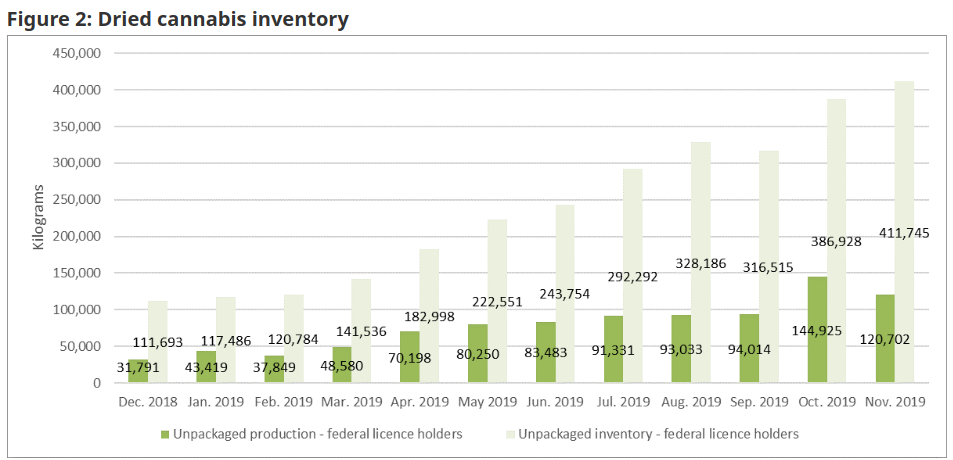

The information removal that most recently got our attention was the sudden change in Health Canada’s reporting of cannabis market data. The Dive has been pointing out for quite some time that ever-growing cannabis inventories were a problem in the context of an effectively flat sales curve, and that it was unlikely that the October 2019 advent of edibles and extract sales would pick up the slack, but it’s hardly an original idea; plain to anyone who can read a chart.

Health Canada changed their reporting beginning in the October period to reflect the new product categories, and made a change to the way they report cannabis sales while they were at it. Kilograms of dried flower and litres of oil – standard metric units of mass and volume – have been replaced by “packaged units,” which, taken literally, come in all different sizes and hold all different volumes.

The inventory is still reported in kilos for dried flower, but publishing the accompanying sales numbers in an effectively meaningless unit robs it of all relevant context.

Health Canada added a “packaged production” metric in kilograms, and applied it retroactively to the data from October, 2018 through September, 2019, but did not provide it for October and November of 2019.

When we emailed Health Canada to ask them what gives, they replied that:

“Given the wide variety of products now authorized for legal sale (e.g., tinctures, capsules, beverages, mints) and their different package sizes and weights, “packaged units” is a consistent and comparable unit of measure for reporting on the categories of production, inventory and sale.”

Despite the fact that

a) packages of different denominations are not consistent or comparable, either to each other or to the kilogram-denominated sales data from months prior to October, and that

b) the agency does not report production of dried cannabis, the largest product category, at all.

Doesn’t look quite as bad without that flat sales line.

Since reporting requirements haven’t changed, one can only guess that Health Canada are trying to make our analysis easier. They might not understand that switching up the units without a way to backward-normalize makes analysts question the integrity of this data, and no longer wish to collect it. Or… maybe they do understand, and that’s the whole point.

The author has no securities or affiliations related to any organization mentioned. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.