Mortgage amortization is the length of time it will take to pay off the entire interest and principle of a mortgage loan, at the agreed upon monthly payment, at the current rate of interest.

In our post about trigger rates, we illustrated that mortgage interest accrues monthly, and when a monthly mortgage payment doesn’t cover the interest accrual, the outstanding balance grows instead of receding.

That’s called “negative mortgage amortization,” and the bank won’t allow it, because it’s bad for business.

A perpetual loan balance, bouncing through time like a snowball, collecting interest as it goes, seems like something the bank could really get behind. But in practice, borrowers are more likely to stop paying when they realize they’ve been backed into an endless commitment.

Negative amortization isn’t illegal in Canada, as near as we can tell, but banks don’t let mortgage balance rates invert into negative amortization, because home owners are their golden geese, and a few negative amortizations could really poison the flock. The mortgage racket only works if they all keep laying golden payment eggs every month.

So variable rate and adjustable rate mortgages are built with clauses that bump the monthly payments when the rate goes up enough that the monthly interest accruals overtake them. When a borrower can’t earn enough to make their monthly payment (or extract it from a tenant), the discussion they have with their loan officer is sure to include extending their period of mortgage amortization.

To Live and Die In… doors.

Readers who paid attention in high school French may notice that mort – death – is the root word of both mortgage and amortization. It’s generally believed to be referring to the death of the loan but, since the mortgage is the loan, and –gage is old French for “pledge,” there are often jokes made about the mort- in “mortgage” referring to the borrower having made a pledge that they’ll be paying off until their death. But that’s not really accurate or fair, because the bank doesn’t care if the borrower is dead; it still wants the money.

Mortgage amortization periods are set at the mortgage’s inception but, in practice, since even fixed rate mortgages are re-financed once or twice over their life, the amortization period is flexible. And it’s into that flexibility that bankers and borrowers push the tension created by rate hikes.

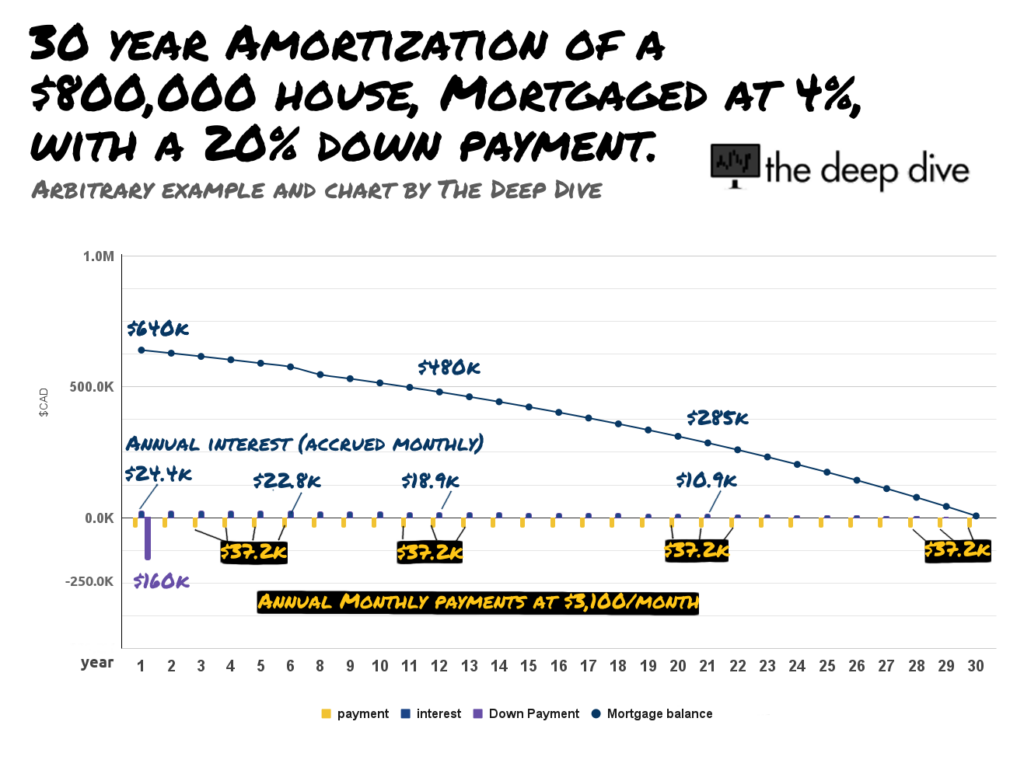

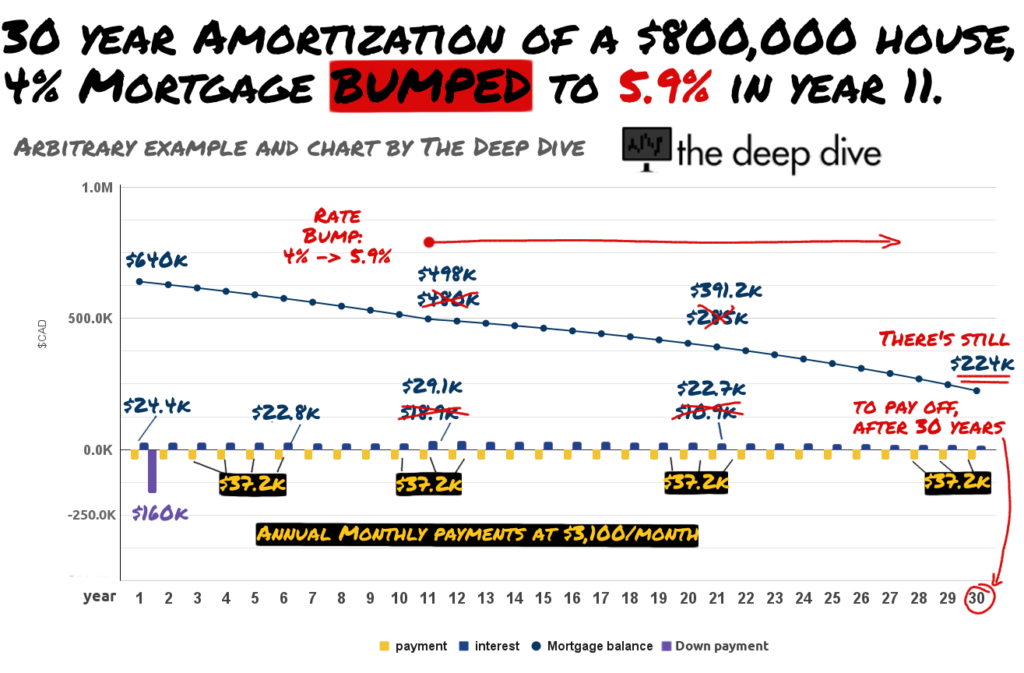

If our Example Borrower from the trigger rate post cruised along for the whole term of their 4% mortgage paying $3,100/month…

…they would be on track to pay the house off in 30 years. A 30 year mortgage amortization.

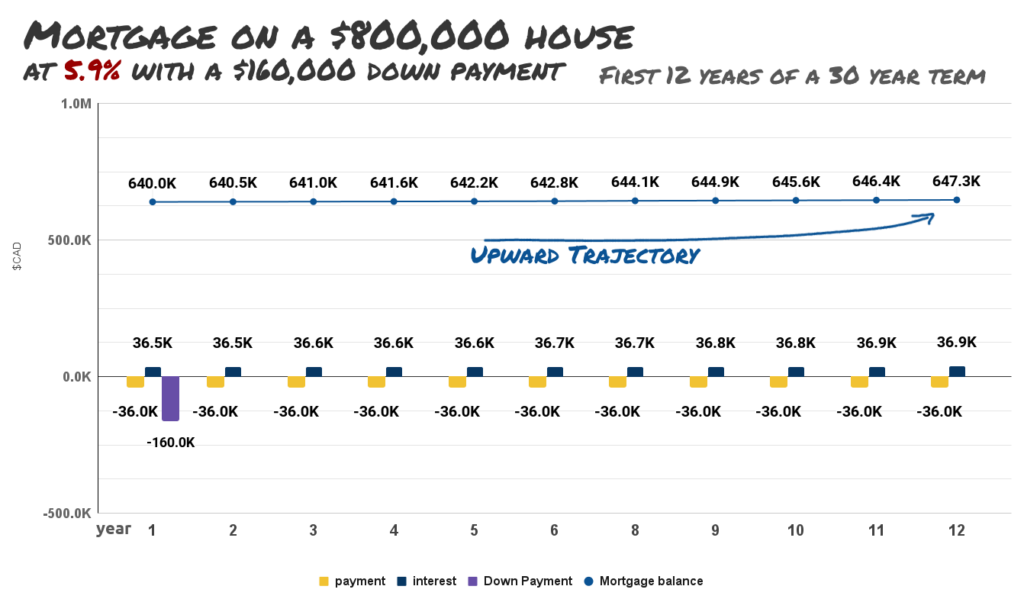

But, along comes the end of the tenth year, Adjustment Day. The bank jacked the rates, so now the mortgage interest is 5.9% per year.

The $3,100 monthly payments still cover the monthly interest accruals ($29,100 on the $498,000 left in year eleven), but at that rate…

… there is still $224,000 to pay off after 30 years.

Example Borrower is already pretty much tapped out at $3,100/month, and it isn’t like the bank is in a position to cut them any slack. A Canadian bank might seem like it has a lot of money, because of the enormous profits it turns every year, and the fact that it has a balance sheet larger than most small countries. And one might surmise that, since banks are built around a government charter that gives them access to the raw money, from the government-owned central bank, and also built around cut-rate deposit insurance and mortgage insurance facilitated by the government, that they might want to give our wage-earning, tax-paying borrower a break… but they have their shareholders to think of.

“I’m sorry, sir. Since we can’t bleed you for more, we’ll have to bleed you for longer. And more.”

So the banker adjusts his glasses, sits down at one of those old-fashioned adding machines, pulls the handle a few times to make that big KER-CHUNK sound, writes something down, and determines that, to get this mortgage paid off in 30 years, at the new rate, the payments are going to have to go up to… (KER-CHUNK!) $3,600/month. How does that sound?

It sounds horrible! Example Borrower just coughed up $800 at the dealership to fix the minivan, because financing a new one is out of the question, and the kids are getting old enough for hockey… so even the $3,100 is more than they can handle!

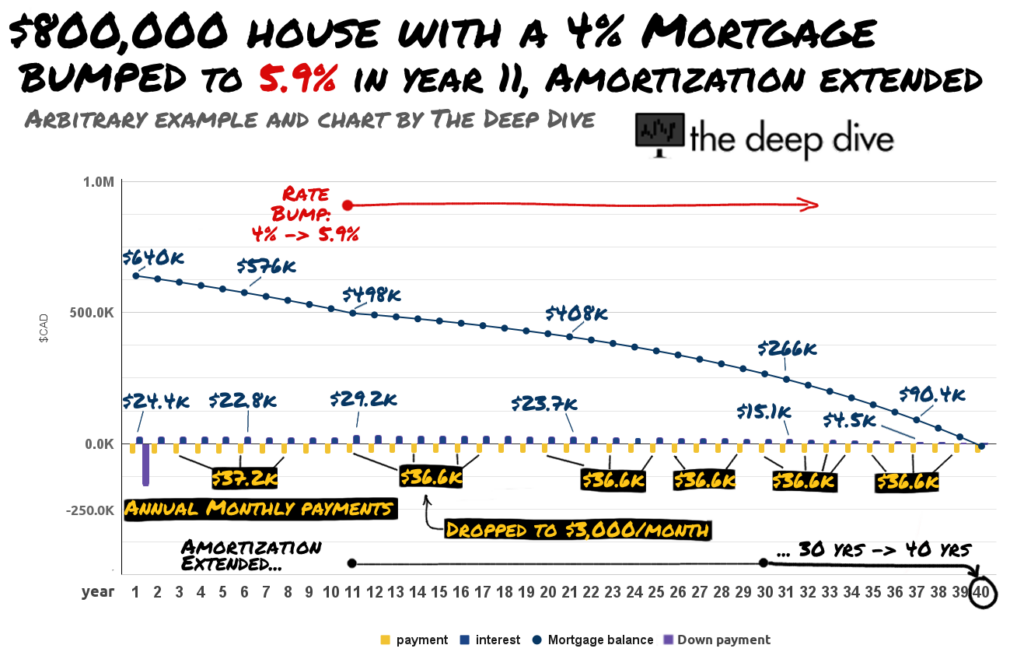

But if we’re pushing the amortization out anyhow, we might be able to work in some short term relief.

If we pay this mortgage off over 40 years, we can drop that monthly payment to $3,000, and get those kids skating.

40 years is a long time. It’s beyond the useful life of the roof on the house, and long enough for a child they had in year five to grow up, move out, finish college, move back into the basement, and promise to start contributing to the housing payments as soon as his youtube channel really gets going.

At the end of the original 30 year mortgage at 4%, the $800,000 house was going to cost Example Borrower $1.27 million in principle and interest. With the new rate, lower payments, and extended amortization, the house is going to cost Example Borrower $1.56 milion in principle and interest – nearly twice the sticker price of the house… assuming the rate doesn’t change again, and not including the cost of basic maintenance and mandatory home insurance.

So, if the minivan holds out long enough to get that kid to hockey practice consistently, he had better turn in to the next Connor McDavid.

Feature image adapted from an original sketch by Stephane Turgeon.