This column is on the record with an opinion that the Rogers Communications Inc. (TSX:RCI.A) (TSX:RCI.B) saga drew more media attention than it deserved, and now that the papers have moved on without ever getting to the bottom of what these spoiled brats were fighting about, it’s worth taking an educated guess at what it might have been, as part of a closer look at what was covered.

Dual class share structures

The weight that Ed Rogers threw around to end up re-gaining control of the publicly listed company was contained within the gravity of the A-class voting shares, materially all of which are controlled by the Rogers Family Trust, the trustees apparently having sided with him over his sister, Martha Rogers.

One of the two most notable Globe and Mail articles about the Rogers share structure appeared in this past Thursday’s edition. Veteran business columnist Andrew Coyne wondered if Rogers was a mess because of its dual class share structure, but never really got around to explaining what about it constituted a “mess.” The Rogers businesses and its listed equities are all marching along in relative order.

The networks and pro sports franchises it’s responsible for are taking up the same parts of the national background as they ever did, the dividends are being paid out on the number, and it’s in the middle of a takeover of its largest non-competitor, Shaw Communications (TSX:SJR.A) (TSX:SJR.B). But a Canadian business family of nobility ending up in court is unsightly so, in terms of appearances, we’ll take Coyne’s point.

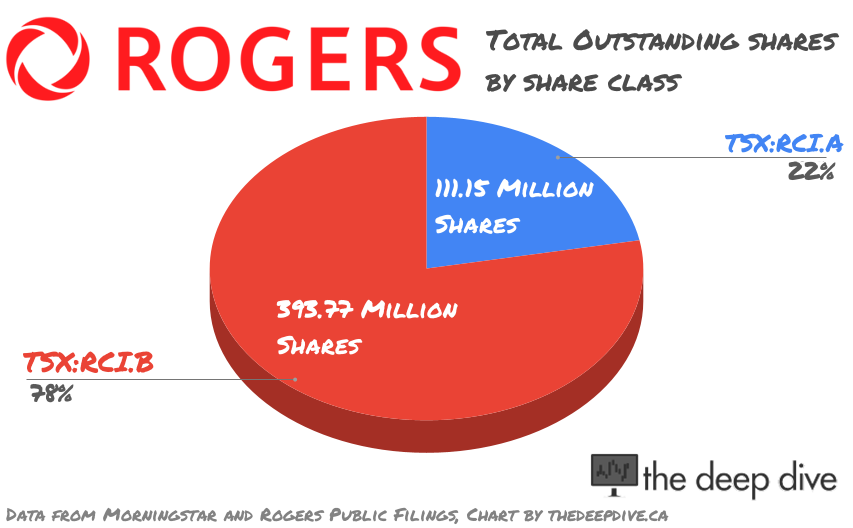

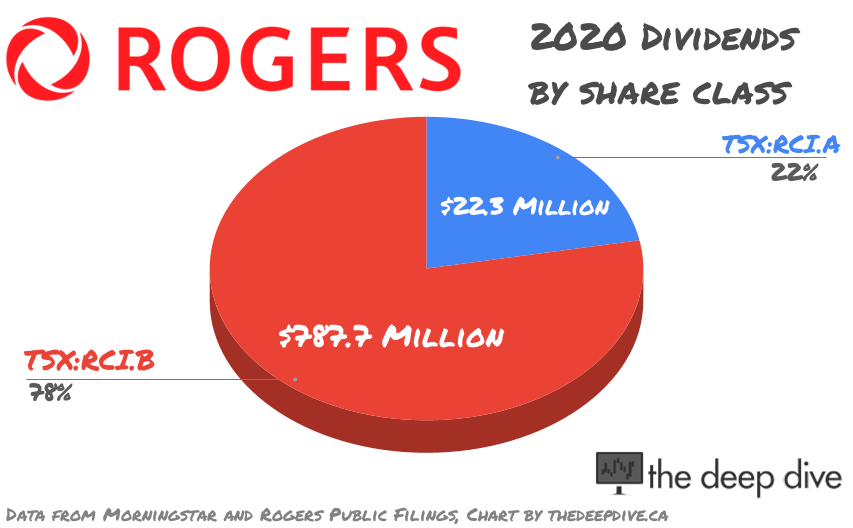

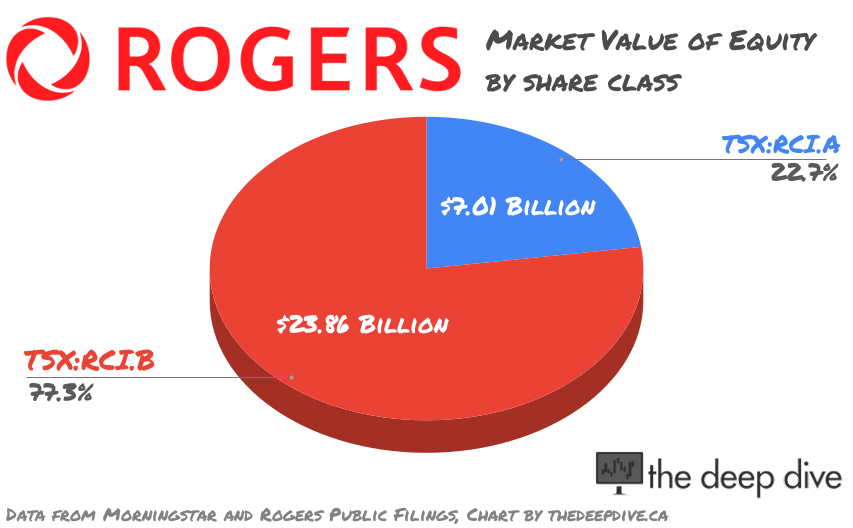

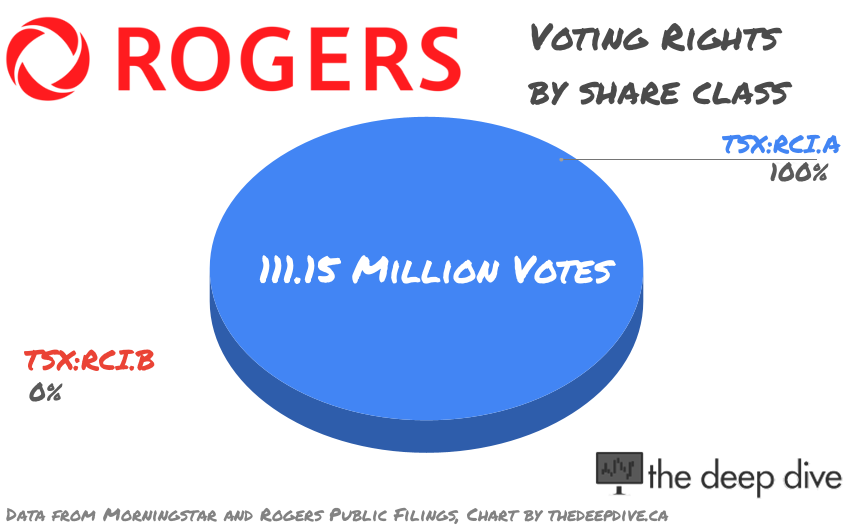

Rogers presently lists 111.2 million class A voting shares, and 393.8 million class B shares, which carry no voting rights, but are entitled to an equal share of declared dividends. Those shareholders receive 78% of the dividends paid out…

…own 77% of the company’s market value…

and, as we mentioned, control 0% of the votes.

Coyne describes this lack of votes as a “violation of the sacred principle of one share and one vote,” because, apparently, at the Globe‘s business desk, much like everywhere else, capitalism is a religion.

The “sacred principle,” is foregone in this case by the fact that the class B shareholders agreed to the terms when they signed up to buy the stock. To Catherine McCall, Executive Director of the Canadian Council for Good Governance, and guest contributor to The Globe and Mail, that doesn’t mean a whole lot.

In the era of index fund investing, the argument goes, many of the beneficiary shareholders are purchasing the stock as part of a fund, and might not understand that they don’t have a vote. McCall doesn’t advance any argument that passive investors ought to be better informed, preferring instead to see dual class shares as a matter of…

Environmental and Social Governance

McCall argues in her November 4th column that Rogers’ broader stakeholders, including their employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate, ought to be considered in its governance, and that a power-base concentrated with the founders’ family does not give those groups any standing, which is true, but her specious assertion that a board of directors voted on by whomever happens to own the non-voting equity would have any more deference to those groups than the Rogers Family Trust does, or in fact to any group but themselves, isn’t convincing.

The CCGG is proposing changes in law that would limit the ability of companies to issue subordinate share classes, including a sunset clause that would eliminate voting disparities after five years. It isn’t clear whether the council envisions this clause being applied to existing dual class share structures like Rogers’, or just to new ones, but a policy like that would be a pretty sweet deal for the class B shareholders.

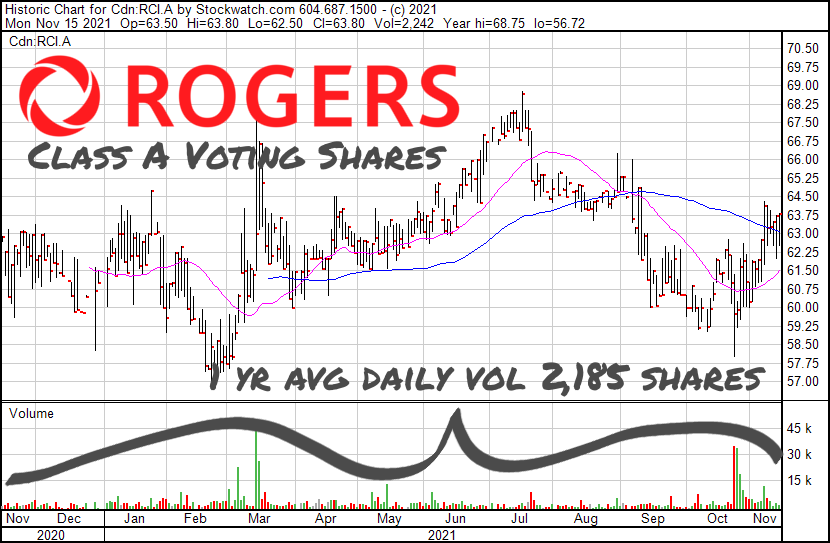

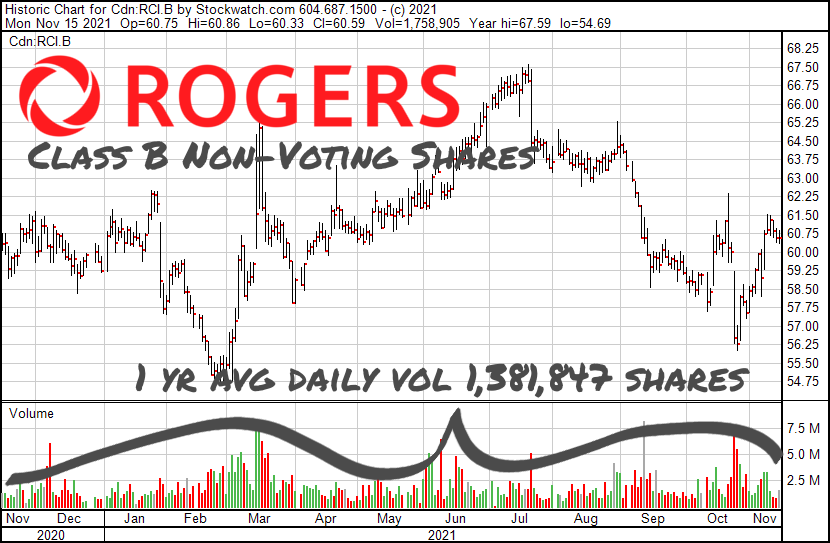

On paper, the A-shares and B-shares trade for about the same value (RCI.A: $63.10 at the time of this writing, RCI.B: $60.59). But the A shares being hoarded by the Rogers family limits their liquidity.

They trade a tiny fraction of the volume of their non-voting counterparts (accounting for relative share counts), because they aren’t generally for sale. If a voting block were to be made available, it would almost certainly sell for more than its share of the $7 billion the market values it at now.

The sunset clause that the CCGG describes would turn those B-shares into a voting block in an act of de-facto alchemy, making control of the company available to anyone who wants to pay for it, showing us what voting control of Rogers is actually worth, and giving the B-shareholders an opportunity to cash a check for the difference.

Coyne makes this point in his summation, reminding us that the CCGG represents the interests of the pension funds and other institutional investors that would benefit the most from this rapid value change, but McCall doesn’t even acknowledge it. Instead, she frames the one-share-one-vote principle as a crucial component of Environmental and Social Governance; the cornerstone principle of the newish sect of “woke” capitalism that casts itself as a brand of the religion of capital that considers the interests of stakeholders other than the shareholders, without committing the heresy of giving them any equity.

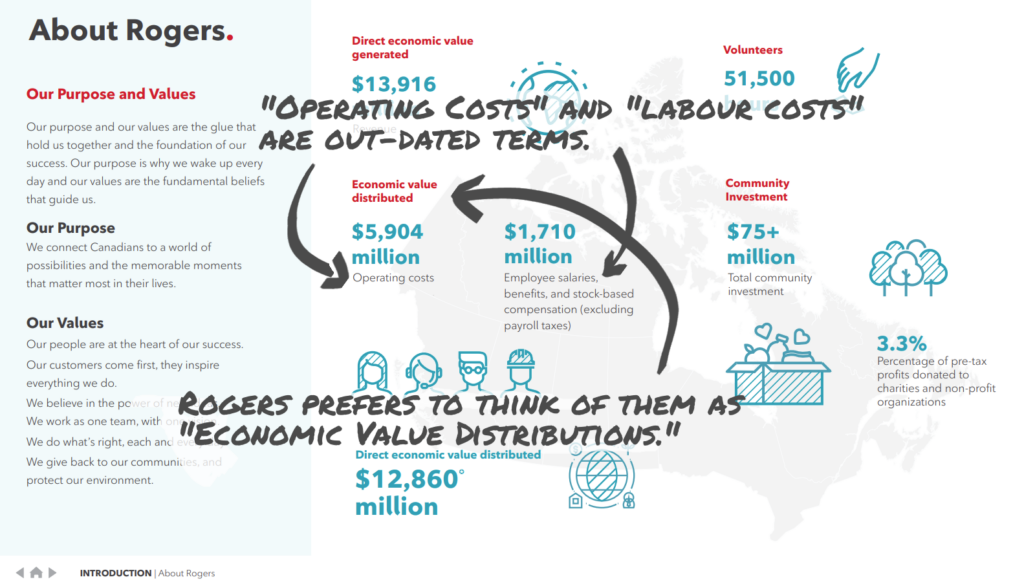

Martha Rogers is the chair of Rogers’ ESG committee. Typical of the ESG efforts of companies Rogers’ size, its chief product is an annual report in which the company pats itself on the back for the money it pays its employees, the 3% of its pre-tax profit that goes to charity, and every free cell phone it’s ever given to anyone.

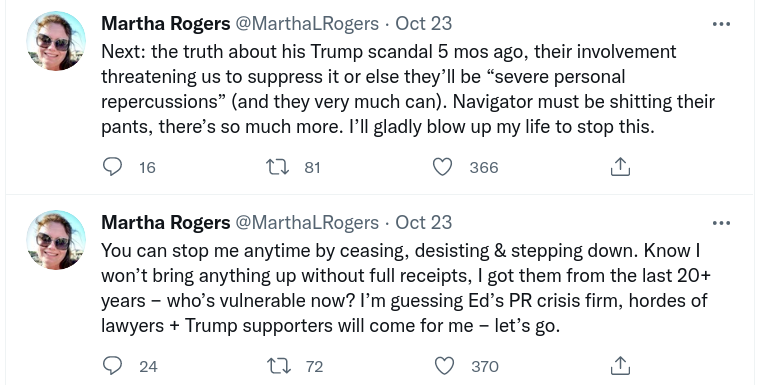

Martha is surely proud of Rogers’ ESG efforts, and presumably under the impression that it makes a difference. We were watching her twitter feed closely following thinly veiled threats to dish dirt on the Trustees and board of directors of the Rogers Family Trust, but weren’t all that surprised when none came.

A closer look makes us wonder if maybe it did.

Martha Rogers thinking that association with Donald Trump is the type of reputation damage that would give her leverage over these board members would explain a lot. Her repeated use of the hashtag #OldGuardDown is an apparent awareness of a growing sentiment that the old money running institutions like Rogers aren’t doing anyone any favors, and Martha is basically on the money. The idea that a single family can control such a large piece of the country’s communications and broadcast infrastructure feels unjust.

But she hasn’t advanced any type of coherent argument that a board of her appointment, or a board appointed with input from the B-class shareholders, would somehow make this communications conglomerate any better managed, because there isn’t one. The differences in how Ed Rogers is going to run the company and how any other capitalist would run the company aren’t likely to have any significance to anyone other than the respective groups of shareholders.

But the tenets at the heart of the ESG-based cult of capitalism are that intention matters. That the pure of heart can make a powerful company less terrible by their very presence. It occurs through stewardship, governance, and everything short of affording the people they’re claiming to help a meaningful stake in the enterprise.

Naturally, investors inclined to feel good about the damage their money is doing by keeping an eye on the ESG profile of their portfolio are more than welcome to purchase a stake. These days, there are even index funds that aggregate companies that are well-governed, environmentally and socially speaking, so as to take the guesswork out of it.

Information for this briefing was found via Sedar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.