The gold bull continues apace, and is the only consistent source of strength in venture-class securities so far in 2020. This column has covered the market’s recent interest in both early and advanced stage exploration companies, and will eventually get around to production-stage operators when we work our way through the smaller equities and the market takes us there. Right now, it’s telling us that royalty companies are the focus.

Metalla Royalty and Streaming (TSXV: MTA) (NYSE: MTA) and Ely Gold Royalties (TSXV: ELY) have both shown recent strength in relation to their peers as open market money flows fixed cost, high-payout model of precious metals royalty and streaming companies. While royalties themselves aren’t a new idea (probably invented by some monarch or record executive, we’ll look into it) the concept of a listed equity that owns and generates mineral royalties if fairly modern. The first company of note to operate that way was Franco Nevada (TSX: FNV) (NYSE: FNV). The model has been copied with occasional success ever since, but only one company has been able to use it to significant effect, buying up imitators who mattered, and leaving the ones who didn’t in the dust. We’re going to preview a Deep Dive into this market’s royalty equity movers with a look at the original King, to give readers an idea about what these are supposed to grow into (or possibly be become part of).

Pierre Lassonde and Seymour Schulich pioneered the gold royalty company concept in the 1980s, buying up royalties on Nevada gold properties in the developing Carlin trend. Pubcos that offered investors exposure to oil and gas royalties had been long established, the quick payoff on oil and gas wells being something that bankers knew what to do with instinctively. But Lassonde and Schulich were the first to pay cash for gold royalties held by prospectors at their net-present value, and put them in a holding company. They also pioneered the purchase of royalty interests in developing projects. In contrast to equity interests, royalties offer investors an interest in the project, payable at the time of production, that can’t be diluted by future share offerings. This generally limits liquidity but, if written correctly and attached to the mineral title, limits exposure to the equity risk that often chews up more than one company before a property is ever produced from.

FNV went public for the second time in 2007, using the IPO proceeds to purchase a $1.2 billion royalty portfolio from Newmont (TSX: NMT) (NYSE: NEM), and has been an exemplary performer in the context of the resource sector ever since.

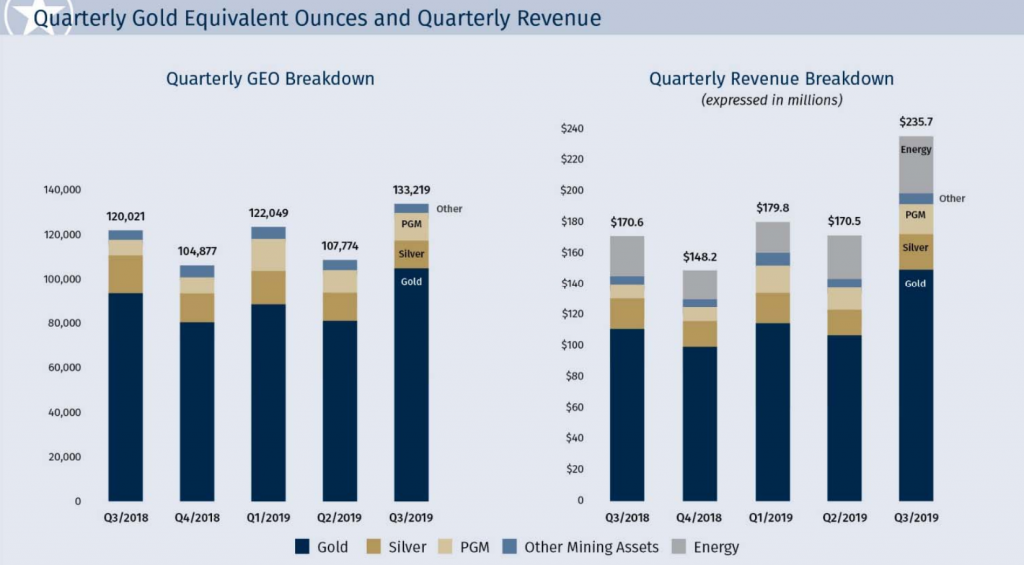

Franco Nevada’s recent bull run has taken it to a market cap of US$21.1 billion, about 11 times their annualized earnings, and carries a net asset value just shy of $5 billion. In their most recent quarter (ending September, 2019), FNV generated $126 million in gross profit on $253.7 million worth of sales, a healthy 53% margin.

Franco tracks their production in Gold Equivalent Ounces (GEO) telegraphing to the market that the mineral diversity in their royalty portfolio is a hedge of sorts. All of the royalties that Franco Nevada bothers telling us about are in production-stage properties. This company is built to track and outperform the gold price, and is very proud that they’re able to do so. We did up a chart of FNV’s performance vs the Sprott Precious Metals ETF (TSX: CEF) before cracking the MD&A, only to find out that Franco plots themselves against the gold price in their very first chart. The stock outperforms gold over any reasonable period by any reasonable measure.

The company’s long-time management has a track record of getting the most out of their banking relationships and putting that on the bottom line for their shareholders. They borrow money through two credit facilities, one of which maxes out at $1 billion, and charges LIBOR+ 1%. That facility presently has a $85 million outstanding balance. A second credit facility, which charges at 0.85% over LIBOR for a max of $160 million is fully extended. They could surely get more if they asked for it.

Because of their size, Franco Nevada isn’t in the habit of doing small deals. Most of their purchases are more than $20 million dollars and arise as an opportunity for mining companies to finance pre or post-production expansion of their reserve base. They’ve come to leave the purchase of royalties on exploration-stage assets to the smaller royalty companies who have taken up their model. Stay tuned for a closer look at those in parts two and three.

The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.