Corruption, safety issues, and personality politics–how did a nuclear facility that cost billions to the country never get to yield a single watt of electricity in more than three decades?

As global energy prices continue to soar, the world is turning to alternatives–one of which is nuclear power. While some countries are rushing to have their nuclear facilities extended beyond scheduled decommissioning or building more plants, the Philippines had one built more than three decades ago.

But, in all those years, it was never run.

As talks of reviving the country’s only nuclear power plant have resumed, it would be noteworthy to look at the story of the Southeast Asian country’s mothballed facility.

Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

The construction of the 620-megawatt Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) started in 1976, around four years after then-President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. The facility was supposed to be the dictator’s response to the 1973 oil crisis.

The plant was supposed to provide an alternative source of electricity for the mainland Luzon in a country that’s heavily dependent on oil imports.

General Electric and Westinghouse Electric both submitted bids for the construction. General Electric presented four full volumes detailing cost and specifications, conducted nuclear power seminars in Manila, and invited Philippine officials to visit its plant in California–with estimated costs of $700 million. Westinghouse initially submitted a vague, undetailed $500-million bid for two plants.

The presidential committee charged with overseeing the project favoured General Electric’s proposal, but in June 1974, Marcos signed a letter of intent giving the project to Westinghouse. After winning the contract, Westinghouse made a revised proposal totaling $1.2 billion for just one reactor—nearly 400% more than the original bid of $500 million.

The facility design is a two-loop pressurized water reactor system and was scheduled to be in operation by 1982.

Around this time, the country was already feeling the effects of its growing national debt and declining economy. In 1976, the Philippine economy had a GDP of $17 billion and a government budget of $1.5 billion.

With the project’s staggering price tag, the government sought help from the Export-Import Bank of the United States in Washington, DC. The bank’s chairman William J. Casey approved $277 million in direct loans and $367 million in loan guarantees in 1975, arguably the largest loan package the bank had approved anywhere.

At best, it is estimated that the power plant would have supplied electricity of around 620,000 kilowatts, or enough for about 15% of Luzon’s population.

Safety concerns

After three years of construction, the BNPP was briefly halted due to a nuclear accident in Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania, U.S.A in March 1979. This caused the Philippine government to reconsider the safety of its own nuclear facility, establishing a commission in June 1979 to explore the “dangers that may arise from the operation of the proposed nuclear power plant.”

In his letters of instruction to the commission dated in June 1979, Marcos noted that he directed his Energy Minister “to require Westinghouse to send experts to the Philippines to explain doubts that have arisen” about a week following the Three Mile Island accident. “Why has not Westinghouse done so up to now?” Marcos asked.

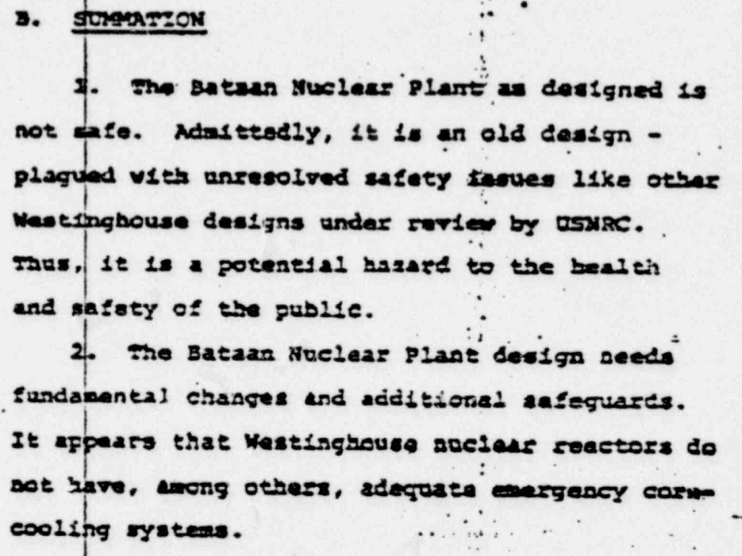

In its report, the commission said that the BNPP “as designed is not safe… plagued with unresolved safety issues.” It also pointed out numerous construction and design flaws, such as unsecure nuclear waste storage and insufficient emergency core-cooling systems.

Nuclear engineer Robert Pollard of the Union of Concerned Scientists also submitted a declaration to the commission, stating that the BNPP is “not safe and will not be inexpensive” based on his research.

The commission also noted that Westinghouse only sent its panel of experts to see the president long after the commission was created, saying “this obviously demonstrates unwarranted delay and lack of immediate concern over the safety of the plant.”

Source: US Nuclear Regulatory Commission

Marcos took the commission’s summation that construction of the BNPP will not continue unless Westinghouse “introduces fundamental changes in design and adapts additional, adequate and acceptable safeguards to ensure its safety and protect the health of the public.”

To address these concerns, Westinghouse and the Philippine government–through state-owned electric utility National Power Corporation (NPC)–renegotiated the contract. The final price after bargaining was $1.8 billion: $55 million of the $700 million increase was for new safety equipment while the balance reflected higher interest rates and inflation. Since then, the project cost has risen to $2.3 billion, owing to increased capitalized interest and delay expenses.

Westinghouse resumed construction in 1981, adamant to keep Marcos’ timetable. William Albert–an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) adviser to the Philippine Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) and a recommended expert by Westinghouse and US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC)–thought the contractor was just rushing to finish the job as the power of the country’s strongman was seen to be fading.

“Westinghouse sensed a change in the political winds and wanted to get out of there,” Albert said.

Issues were still hounding about the construction of the plant, particularly with how the project was seemingly being fulfilled in a railroad fashion. A 1986 Fortune Magazine article chronicled the details of the construction, noting how experts were then saying that “deficiencies remained in wiring, in brackets that support the miles of electrical cable and pipes that carry steam and water (some of it radioactive), and in several other areas.”

Albert recounted a severe issue involving welds in a system of thousands of hangers for water pipes that snake around the plant. Welders utilize a metal called weld rod, which must be kept dry in humid Bataan since moisture might cause a seam to split. To maintain the rod dry, it is stored in a compact, box-shaped electric oven that must be plugged in at all times.

However, the welders at the company would frequently play a game in which they would see how long they could mislead inspectors by leaving their ovens unplugged. According to Albert, the welders did not want to bother running extension cords to the ovens.

In June 1984, an IAEA team inspecting the plant discovered that many of the valves controlling water flow were inadequately marked or unmarked. Albert claimed that even after Westinghouse had declared the facility complete in February 1985, the valves were still poorly marked.

Josue Polintan, then-NPC senior vice president in charge of the plant, agreed that quality control was insufficient, but said Westinghouse inspectors were not to blame.

”If the guys at Westinghouse found out about it,” Polintan said, ”they would try to fix the problems, but their workers would try to cover up and Westinghouse couldn’t possibly catch it all.”

Westinghouse bases its defense of construction defects on reports issued in February 1985 by an IAEA inspection team and the technical staff of the PAEC. Both committees decided that the facility “meets international safety standards followed by 26 nations” and was suitable for core loading, according to Westinghouse. The staff report of the commission does not provide the endorsement that Westinghouse claims.

“How could two IAEA teams… arrive at such different conclusions just eight months apart?” the Fortune Magazine article asked. The members of the second team–with the exception of one engineer who visited in 1984 and discovered some ongoing problems with the electrical wires when he returned in 1985–were not construction professionals. They were experts in topics such as training and radiation exposure.

Albert also believed, and other USNRC safety specialists concurred, that the second IAEA team could not have conducted a complete inspection in the week it was at the plant.

The chosen site for the plant is also within 25 miles of three geologic faults and just five miles from the Mount Natib volcano, although the latter hasn’t erupted in an estimated 27,000 years.

Despite all these, NPC applied to the PAEC for a license to operate the facility on time in June 1984. Westinghouse deemed the facility ready for operation in January of the following year and turned it over to the state-owned electric firm. The majority of Westinghouse personnel had left by the end of February, and the last construction worker left in May.

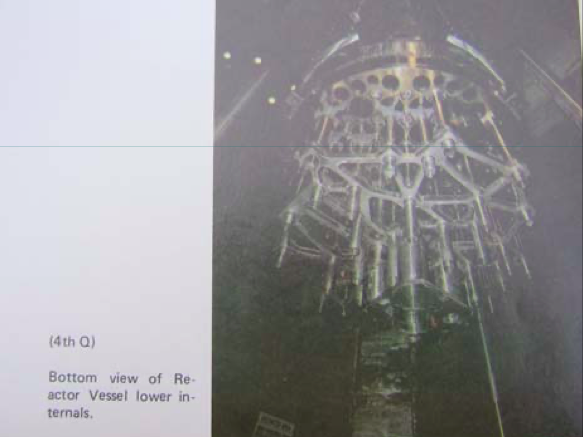

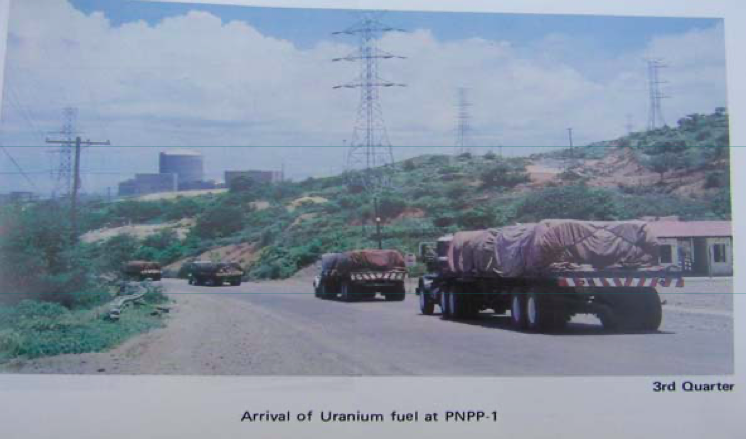

Afterwards, hot functional tests were completed and the plant was initiated for synchronization to the grid. A month after, nuclear fuel was already delivered.

While the construction was ongoing, protests had been mounting in dissent to the operation of BNPP. However, these were just an additional issue of the larger, growing demonstration against Marcos’ authoritarian regime.

Following the assassination of Marcos’ primary political opposition–former Senator Benigno Aquino Jr.–civil unrest had been scaling up. Eventually, his wife Corazon Aquino challenged the strongman for the presidency in a snap elections that Marcos himself called.

The sitting president declared victory amid widespread reports of election irregularities and rumored stolen votes. In February 1986, citizens took it to the streets in a mass demonstration on the Philippines’ biggest highway–in what would be later called the EDSA People Power Revolution–and forced Marcos and his family to flee out of the country.

According to a 1986 Los Angeles Times report, around $1.2 billion of the $2.3-billion project remained unpaid after Marcos’ ouster. Aquino then assumed the presidency, signing an executive order saying the Philippine government will assume paying for the remaining debt by NPC.

Only two decades later, in 2007, was the debt fully paid.

Just months into Aquino’s presidency, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion happened in the north of the Ukrainian SSR of what was then the Soviet Union. The country’s first female leader then mothballed BNPP in November 1986, citing “reasons of safety and economy.” She then transferred the plant’s ownership from NPC to the Philippine government, but the state-owned utility company will still be the caretaker until the government “shall have studied and ultimately determined the disposition” of the plant.

The BNPP still stands to this day, with the country spending around $700,000 – $900,000 annually in the plant’s upkeep.

Corruption

The BNPP is arguably one of the symbols of strongman Marcos’ side of cronyism and corrupt authoritarian regime. General Electric was way deep into discussions with NPC after Westinghouse came into picture. Westinghouse’s district manager in the Philippines, Leonard Sabol, was apparently urged to recruit a lobbyist in order to leapfrog General Electric, which led him to Herminio Disini—one of Marcos’ golf partners and whose wife was First Lady Imelda Marcos’s cousin and medical adviser.

Soon after, Disini was able to bring Westinghouse directly to Marcos for a pitch. General Electric, who was then already nine months into negotiations, had only reached a meeting with the president’s executive secretary. The NPC board already went through the formalities of ratifying Marcos’ directive to award the project to Westinghouse on the same day General Electric delivered its full proposal to NPC and the executive secretary.

“There never was any bidding,” then-NPC general manager Ramon Ravanzo said. He also said that it was virtually impossible to bargain with the Westinghouse team after the project cost had started to climb as “they knew about the order [from Marcos] and that [NPC] couldn’t go elsewhere no matter what Westinghouse demanded,” although he wasn’t able to show any direct evidence to the effect.

After Marcos was ousted, Aquino created a special commission to look into her predecessor’s so-called ill-gotten wealth. Investigations led to believe that Marcos received around $80 million from the contract through Disini, which is believed to have been funneled through Westinghouse’s Swiss subsidiary, the entity with whom the BNPP project contract was signed with the NPC.

In 1976, a Westinghouse spokeswoman admitted that the corporation had paid commissions to Disini “for assistance in obtaining the contract and for implementation services.” However, the spokesman refused to comment on the quantity of the fees or reveal exactly what Disini had done for Westinghouse for “proprietary information for commercial and competitive reasons.”

“These claims that money was paid to President Marcos are not new,” said Robert Pugliese, then-vice president and general counsel for Westinghouse. “They have been thoroughly investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the United States Department of Justice. In both instances, Westinghouse was cleared of any impropriety.”

This is close to an estimate made by the Philippine National Computer Center in 1975, which was commissioned by President Marcos’s own committee to select a contractor, that the Westinghouse plant was at least $75 million too expensive in comparison to similar plants being built in Taiwan, South Korea, and Yugoslavia, according to a former committee member.

Westinghouse would later acknowledge paying Disini $17 million between 1976 and 1985, but this was “for legitimate sales commissions.”

The Philippine government would later file a civil suit against Westinghouse and the engineering firm Burns & Roe Associates alleging a bribery plot with Marcos. This would be dismissed in US federal court after a jury trial cleared the companies of the charges.

The commission looking into Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth would conclude that the $50.6 million Disini received in commissions was ill-gotten, which the country’s anti-graft court, Sandiganbayan, concurred and ordered for Disini to return the money.

In 2021, the Supreme Court of the Philippines would order Disini’s estate to repay the government approximately $18.3 million in damages, affirming Sandiganbayan’s judgment.

Reviving plant revival talks

BNPP became idle after Marcos and Aquino’s predecessors decided against commissioning the plant either due to persisting safety concerns or politics.

Albert did not state that the plant “is hopelessly flawed.” He contended back then that Aquino should repair it and bring it back into service but doing so might cost additional hundreds of millions of dollars.

The country’s Energy Department back in 2017 requested specialists from Korea and Russia to conduct a pre-feasibility assessment on the BNPP infrastructure’s integrity. Proposals offered to rehabilitate the nuclear power plant ranged from $1 billion for Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power to $2 – $3 billion based on estimates by Russia’s Rosatom. Rehabilitation is estimated to last up to four years.

However, moves to revive BNPP intensified after Marcos’ son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., won the presidency in May 2022.

“We must build new power plants. We must take advantage of all the best technology that is now available, especially in the areas of renewable energy,” Marcos Jr. said in his first address to Congress. He also recently met with South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol to discuss a potential BNPP collaboration.

According to calculations based on BloombergNEF statistics, a nuclear facility the size of BNPP operating at near peak capacity would have generated around 5% of the Philippines’ power needs last year.

“We are not discarding the Bataan plant, but we have to make sure that it’s safe to revive,” Energy Department Undersecretary Sharon Garin said in an interview, adding that the Marcos Jr. administration intends to appoint a third-party evaluator this year to assess the facility’s feasibility.

Source: Bloomberg

According to a June 2022 poll conducted by pollster PUBLiCUS shortly after Marcos Jr.’s election victory, 59% of Filipinos support the construction of a nuclear power plant. A secondary survey conducted in 2019 by the Energy Department and pollster Social Weather Stations found that 79% of respondents supported reopening the BNPP.

As officials examine competing viewpoints, the Philippines is in desperate need of new energy sources. Investors are discouraged with the country’s power costs that are among the highest in the region, which could potentially shoot up further in five years when one of the state’s important energy sources, the Malampaya gas field, is expected to be depleted.

Rep. Mark Cojuangco, who chairs a congressional committee on nuclear energy and author of the bill to recommission BNPP, said that Marcos Jr.’s father has been “proven correct” by history.

“If we used the nuclear plant, we will not have these problems,” Conjuangco said. “Now [Marcos Jr.] has to take a stand and finally fight for this.”

During a congressional hearing on his bill, as Conjuangco was asking the committee to authorize raising $1 billion for BNPP’s rehabilitation, he was asked of any studies to support his claims but struggled to provide new arguments aside from some Wikipedia articles and what has already been produced during Marcos’ time.

“Cojuangco subsequently replied that studies have been done since US President Eisenhower’s time as well as under Philippine president Marcos’ administration,” wrote renewable energy advocate and author Roberto Verzola, who was invited to the hearing as an expert. “Aside from these, all he could cite were some Wikipedia articles, quotes from Greenpeace renegade Patrick Moore and claims that identical NPPs in South Korea, Slovenia and Brazil were still running today with ‘impeccable safety records,’ which was not quite true.”

In a recent Twitter thread, nuclear energy consulting firm Radiant Energy Managing Director Mark Nelson relayed his thoughts on the BNPP after visiting the plant via an invitation from Cojuangco, claiming he “became a believer” in the prospects of the nearly four-decade old decommissioned facility.

A few months ago I was invited by Philippine Congressman @markcojuangco to see something few have ever seen: a nuclear plant frozen in time, completed including a trained operating staff, but never turned on.

— Mark Nelson (@energybants) January 15, 2023

I couldn't say yes fast enough. Here are some pictures, with captions. pic.twitter.com/FCdbV7dSzC

On criticisms about BNPP’s structural condition, Nelson noted that even if the plant “had been operating since 1986, it’d be in good working company with other ‘2-loop’ Westinghouse reactors of similar size and age, such as Kori-2 in South Korea and Krško in Slovenia.”

“Instead of turning the reactor on to make electricity to pay down the billions spent in construction, the new government just…didn’t,” wrote Nelson. He added that estimates from Korean experts say “it would take several years of work to meet today’s high post-Fukushima Daiichi standards.”

My trip included meeting with Philippine politicians to answer questions about nuclear energy and to discuss the potential to relaunch Philippine-1.

— Mark Nelson (@energybants) January 15, 2023

I made the argument on TV shows: how lucky for the country to have an already-built nuclear plant in an age of energy shortages! pic.twitter.com/7XRm9kRhCr

But Marcos Jr. is yet to verbally acknowledge the plans for BNPP himself. In his address to Congress, the president would discuss how potential constructions of nuclear power plants should be based on international standards, even considering smaller and newer models.

“We will comply of course with the International Atomic Energy Agency regulations for nuclear power plants as they have been strengthened after Fukushima. In the area of nuclear power, there have been new technologies developed that allow smaller scale modular nuclear plants and other derivations thereof,” he said.

The second-generation president went on to say that public-private partnerships would “play a part in support as funding in this period is limited.”

Information for this briefing was found via Philippines’ Official Gazette, The New York Times, Bloomberg, CNN, Vera Files, Rappler, and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.