The Adani Group, a powerful conglomerate with deep political connections in India, has come under scrutiny for its coal import practices, which appear to involve overpriced transactions. A comprehensive review of customs records by the Financial Times reveals that the group may have imported billions of dollars worth of coal at prices significantly higher than market rates.

This revelation lends credibility to long-standing allegations that Adani, the largest private coal importer in India, has been inflating fuel costs. These inflated costs have, in turn, led millions of Indian consumers and businesses to overpay for electricity. The customs data shows that over the past two years, Adani employed offshore intermediaries based in Taiwan, Dubai, and Singapore to import approximately $5 billion worth of coal, often at prices exceeding double the prevailing market rates.

Note: After our report, Adani Enterprises reported a 42% INCREASE in profit in its coal trading division, despite coal falling 56%.

— Nate Anderson (@NateHindenburg) October 12, 2023

Adani cited 'higher volumes' & vague 'cost optimization'. This never made sense.

The new FT report calls Adani's recent financials into question. pic.twitter.com/RIVGUxCoBp

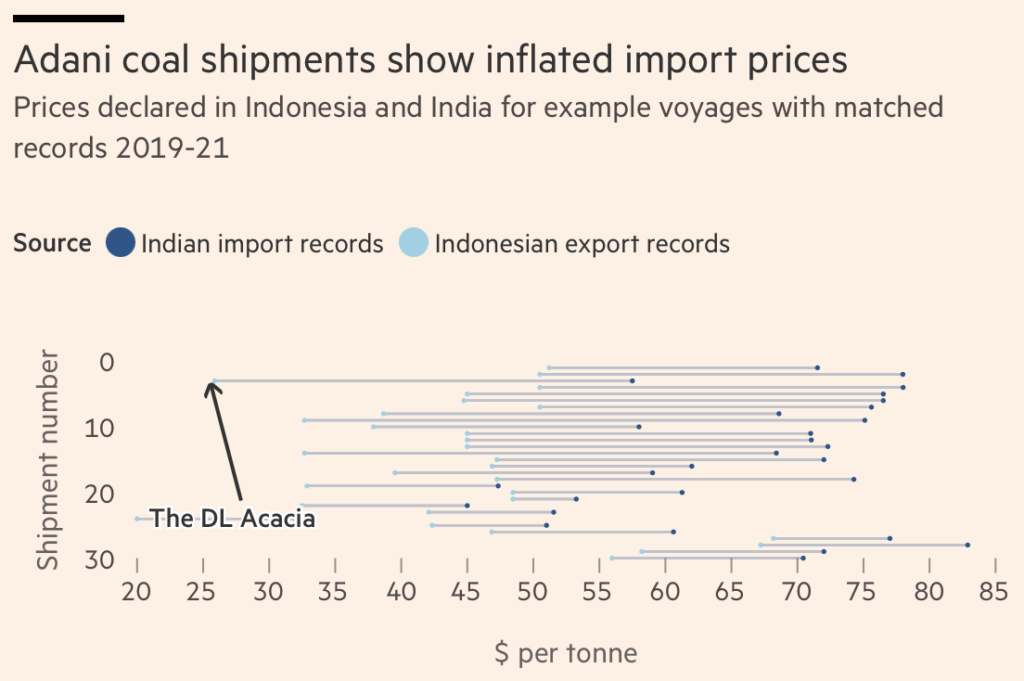

One of the intermediary companies involved in these transactions is owned by a Taiwanese businessman who was recently identified as a substantial hidden shareholder in Adani-affiliated firms. The Financial Times further examined 30 coal shipments from Indonesia to India by an Adani company between 2019 and 2021. Import records consistently indicated significantly higher prices than those reported in corresponding export declarations, with the combined shipments’ value mysteriously increasing by over $70 million during transit.

The Adani Group has denied any wrongdoing, characterizing the FT’s report as an “old, baseless allegation” and a “selective misrepresentation of publicly available facts and information.” The allegations of inflating fuel costs were first raised seven years ago in an investigation conducted by the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI), the Indian finance ministry’s investigative unit responsible for policing economic crime. In 2016, the DRI identified Adani and several other importers for artificially inflating the value of Indonesian coal, potentially overcharging power companies by as much as 50% to 100%.

The DRI’s investigation also revealed a complex scheme in which coal traveled directly from Indonesia to India while supplier invoices were routed through intermediary invoicing agents in a third country, seemingly to create layers akin to trade-based money laundering and to artificially inflate the coal’s landed value. Moreover, opposition politicians in Adani’s home state of Gujarat have accused the group of overcharging for electricity since 2018, citing a letter from the state utility that suggested Adani procured coal at prices significantly higher than the actual market value of Indonesian coal.

The Adani Group claims to have been vindicated by the DRI’s decision this year to withdraw an appeal to the Supreme Court in a case against one of the 40 importers named in the 2016 investigation. In this case, the authenticity of some documents used by the DRI was challenged, and the DRI was found to lack jurisdiction under its narrow remit to enforce customs law.

The unresolved nature of the DRI investigation and the continued alleged practices have raised concerns about the relationship between Adani and the administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Gautam Adani, the group’s founder, is often referred to as “Modi’s Rockefeller.” The Adani Group controls ten listed companies and has grown substantially over the past decade, becoming India’s largest private thermal power company and the largest private port operator.

Earlier this year, Adani’s reputation took a hit when Hindenburg Research, a US short-selling firm, accused the conglomerate of running “the largest con in corporate history.” Hindenburg alleged that Adani used front men and offshore shell companies to manipulate its financial records and artificially inflate share prices. Adani vehemently denies these allegations, describing them as an attack on India itself.

The Adani Group’s oldest and most valuable company, Adani Enterprises, primarily generates its sales and profits from its coal trading division, known as Integrated Resources Management (IRM). The IRM division reported trading 88 million tonnes of coal in its most recent financial year, with a 24% increase in earnings before tax and interest to $101 million on a 6% rise in sales to $2.3 billion.

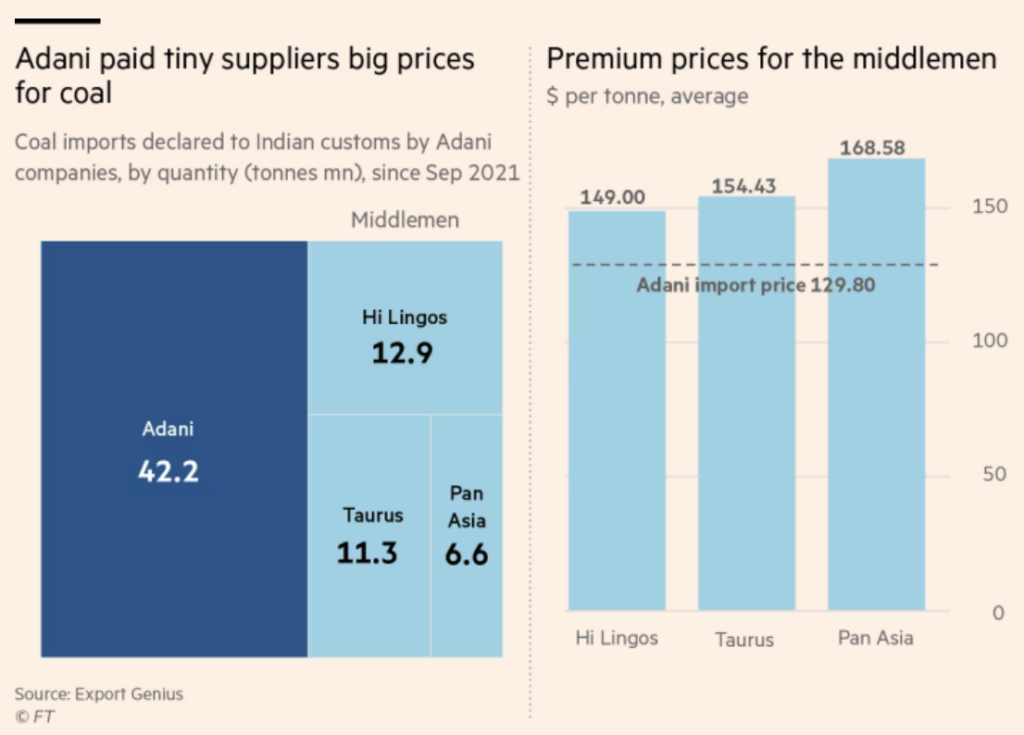

While the IRM’s operating profit margin is in line with industry standards, three intermediary companies—Hi Lingos in Taipei, Taurus Commodities General Trading in Dubai, and Pan Asia Tradelink in Singapore—appear to have made substantial profits supplying coal to Adani. Indian import data since July 2021 suggests that Adani paid a total of $4.8 billion to these three companies for coal, sourced at significant premiums to market prices.

The FT identified 2,000 shipments totaling 73 million tonnes of coal declared as Indian imports by Adani companies between September 2021 and July 2023. For the 42 million tonnes supplied by Adani’s own operations in that time, the declared average price per tonne was $130. However, for the 31 million tonnes supplied by the three intermediaries, the average declared price per tonne was $155, a 20% premium worth nearly $800 million.

Hi Lingos, operating from a residential address in Taipei, was the declared supplier for 12.9 million tonnes of coal in 428 shipments from Australia and Indonesia. Adani paid approximately $2 billion for this coal. Chang Chung-Ling, the owner of Hi Lingos, was previously identified as a potentially controversial shareholder of Adani stock, having held a significant stake in three Adani-listed companies from 2013 to at least early 2017.

The second-largest supplier of coal to Adani in the past two years was the Dubai-based company Taurus, owned by Mohamed Ali Shaban Ahli. Taurus received $1.8 billion for 11.3 million tonnes of coal supplied since September 2021.

Adani appears to have paid the largest average premium to a Singapore-based business, Pan Asia Tradelink, which supplied 6.6 million tonnes of coal for $1.1 billion since September 2021. This represented a 30% premium to the price of coal sourced directly by Adani.

The continued use of these little-known trading houses has raised questions among industry experts. Typically, large coal buyers prefer to partner with established trading houses with strong credit ratings and a reliable track record for commodity deals involving significant sums. The use of lesser-known intermediaries in these transactions has led to concerns about the transparency and legitimacy of these deals.

While it’s possible that the intermediaries supplied high-quality coal that commanded higher prices, the customs records suggest that the prices were considerably above benchmark assessments for coal of that quality. In fact, many of the coal shipments declared by Adani and its intermediaries were priced at a premium to established benchmark prices, causing significant market speculation.

With power generation and distribution being managed by a mix of public and private entities, many of the costs related to electricity production in India are passed on indirectly to consumers. Disputes related to the pricing of coal have been a recurring issue in Indian courts as the price of coal and the quantities imported have increased over the past decade.

The DRI’s investigation in 2016 estimated that the practice of over-invoicing coal could have extracted as much as $5 billion. Recent allegations by opposition politicians in Gujarat indicate that the state government may have made significant excess payments to Adani Power linked to a power purchase agreement. Adani dismisses these allegations as baseless, asserting that coal procurement is conducted transparently through a global bidding process.

While the DRI’s investigation into coal over-invoicing appears to have stalled, other government agencies like the Enforcement Directorate and the Central Bureau of Investigation have pursued cases related to the suspected practice since 2016. These investigations have revealed a complex web of financial transactions that continue to raise concerns about transparency and legality.

As elections approach, opposition politicians have sought to make issues related to coal and crony capitalism prominent, echoing some of the themes that propelled Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party to power in 2014, promising an anti-corruption drive. Coal has been at the center of several prominent scandals in India, and these recent allegations involving the Adani Group and its coal imports are further fueling these debates.

This comes after Financial Times also broke the story of how members of the Adani family seem to have invested their own shares through proxies. Nasser Ali Shaban Ahli from the United Arab Emirates and Chang Chung-Ling from Taiwan, are allegedly using a fund for accumulating and trading substantial holdings in shares of the Adani Group. These two are closely associated with Vinod Adani, the brother of the conglomerate’s founder, Gautam Adani.

Their investments were being overseen by an employee of Vinod Adani, raising concerns about whether they were acting as proxies to circumvent Indian company regulations designed to prevent share price manipulation.

Information for this briefing was found via Financial Times and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.