After surprising investors and economists with widening its 10-year bond yield range, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is caught in a bind after government bond yields have exceeded the upper ceiling of the new range multiple times since. Many are expecting that the country’s central bank will be scrapping its six-year long yield curve control (YCC) policy.

“While increasing the JGB [Japanese government bonds] purchases, the Bank will expand the range of 10-year JGB yield fluctuations from the target level: from between around plus and minus 0.25 percentage points to between around plus and minus 0.5 percentage points,” the central bank’s statement read when it announced the change to its yield curve control policy back in December.

READ: Gold Breaches $1,800-Mark After Bank Of Japan Raised Benchmark Rate

The 10-year JGB jumped to 0.5% in January, the highest since July 2015, as investors anticipated the central bank will need to shift away from its ultra-easy monetary policy. Bond yields have risen since then and exceeded the upper range at least twice, causing the central bank to launch emergency bond purchases in order to halt the bond sell-off. According to Nikkei, the BOJ purchased JGBs worth more than 2 trillion yen ($15.6 billion) on Monday, after spending almost 10 trillion yen ($72 billion) the week before.

Oh. My. God. So far in January, BoJ has bought 13 trillion Yen in JGBs to hold its 0.5% cap on 10-year yield. That's almost 26 trillion if we extrapolate this pace to the rest of the month. Unsustainable. Time is rapidly running out for BoJ yield curve control. With @econchart pic.twitter.com/cHDaUMrFng

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) January 13, 2023

To scrap or not to scrap

The BOJ’s decision to widen the yield range did not mention inflation as a basis but emphasized the government bond market’s poor functioning and disparities between the 10-year JGB yield and the yield on bonds of other maturities. But many analysts saw the decision as setting the framework for exiting a decade of stimulus policies.

Following the overheated bond market, some economists say that the repercussions of the wider yield range may push BOJ to drop YCC altogether.

“Our client conversations suggest domestic investors now see YCC removal as a base case,” the Bank of America Global Research’s economists wrote, adding that scrapping the ultra-easy policy would be viewed as similar to a rate hike.

Morgan Stanley’s Japan Chief Economist Takeshi Yamaguchi also said his team is “acknowledge lingering risk of the BoJ suddenly modifying or abolishing the YCC approach at each future meeting.”

Paul Mackel, HSBC’s global head of FX research, however said that they anticipate the BOJ will not scrap YCC but the central bank will increase the range to 75 basis points each side of its 0% target for 10-year JGBs.

The BOJ is also nearing the end of the selection process for its new BOJ governor and two deputies; current governor Haruhiko Kuroda is set to step down in April, by which most observers believe that the central bank would change its policy under new leadership.

On the other hand, the Liberal Democratic Party’s upper house secretary general Hiroshige Seko believes the BOJ should continue on with its aggressive monetary easing program, adding that the December surprise adjustment of the bond yield range does not imply a strategic shift away from its ultra-easing policy.

“The BOJ should keep going in the current direction,” Seko said in an interview on Friday. “Now is not the time for making a major policy change.”

Seko, a former economy minister, added that it would also be premature to begin withdrawing stimulus while demand in Japan’s economy continues to lag behind supply.

The rise and fall of the curve

After a prolonged period of economic stagnation and ultralow inflation, the BOJ implemented its yield curve control mechanism in September 2016, with the goal of raising inflation toward its 2% target.

After years of massive bond purchases failed to spark inflation, the BOJ reduced short-term interest rates below zero in January 2016 to avert an unexpected yen surge. The move crushed yields throughout the curve, infuriating financial firms that watched their investment gains evaporate.

Eight months later, the central bank adopted YCC by adding a 0% target for 10-year bond yields to its -0.1% short-term rate target. The objective was to manipulate the yield curve’s form in order to decrease short- to medium-term rates, which affect corporate borrowers, without undermining super-long yields and cutting profits for pension funds and life insurers.

The BOJ’s bond shopping spree ended up with the central bank owning as much as half the bond market. YCC allowed it to buy only what was required to meet its 0% yield target.

But low inflation forced the central bank to keep the policy longer. This led to bond yields trading in a narrow range, and trading volume decreased.

To address such consequences, the BOJ stated in July 2018 that the 10-year yield could now fluctuate 0.1% above or below zero. In March 2021, the bank expanded the range to 0.25% in either direction in order to resurrect a market that had been paralyzed by its purchases.

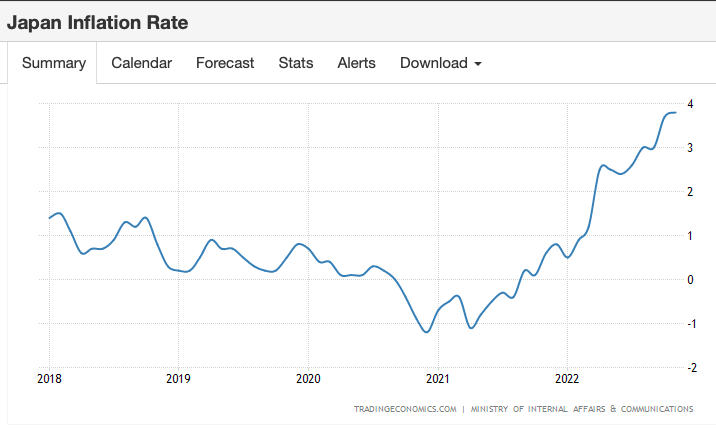

Fast forward to December 2022 when the range was further expanded to 0.5% above or below zero, with inflation striking up at 3.8% in November–above the bank’s target of 2%.

When inflation was low and the chances of meeting the BOJ’s CPI target were modest, YCC functioned well because investors could sit on a pile of government debt that guaranteed secure profits. But with inflation currently at its steepest rise and expected to hit 4% for December–a 41-year high–investors anticipate the yields would be crushed with a possible rate hike that would follow. This then spurred the recent high volume of bond selling.

Market strategist Matt Simpson of City Index does not expect the YCC to be removed this week, but instead sees the central bank raising its inflation target from 2% to a range of 2-3%.

“I don’t think the BOJ will scrap their inflation target altogether, but they might announce a target range of 2-3%,” Simpson told CNBC. “We know that the [Prime Minister Fumio Kishida] has been calling for more flexibility with the inflation target, and this seems like a plausible compromise from the BOJ.”

Under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Japan implemented a reflationary policy led by monetary stimulus, which helped bring the world’s third largest economy out of 15 years of deflation. However, financial markets are now more concerned with if and when the central bank may reduce monetary stimulus in response to substantial increases in inflation–a u-turn from the country’s so-called Abenomics.

Bank of Japan fears a lock of market functioning due to 8/9 yields trading above 10yr bond yields, which is the most urgent issue for them to deal with

— AndreasStenoLarsen (@AndreasSteno) January 16, 2023

3/n pic.twitter.com/88vFa1vKRg

Information for this briefing was found via Financial Post, CNBC, Reuters, and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.