We’re beginning to regret having equipped The Dive’s custom apocalypse bunker in an undisclosed location with a phone, because the damned thing continues to ring with people asking if we think the bottom is in. That usually means it isn’t and, in this case, it feels like the violence of the initial move (and the ones that came after it for that matter) rattled many into over-clocking the distance of the fall.

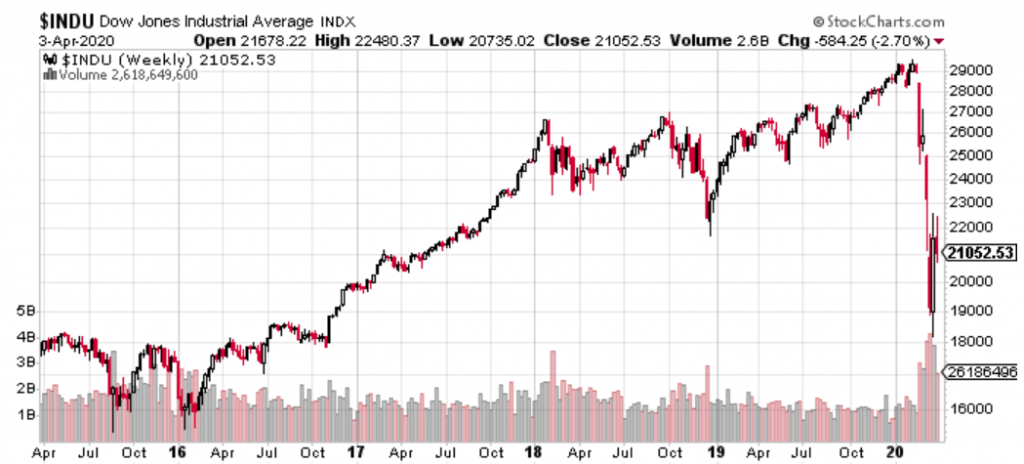

The Dow hasn’t seen the March 23rd low of 18,591 since… the fall of 2016.

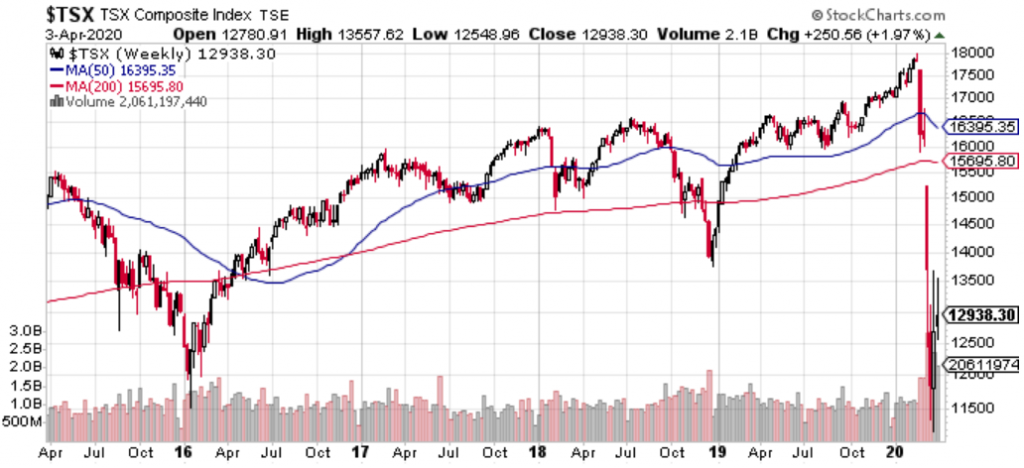

The S&P TSX Composite just bounced off of a 2016 bottom.

The NASDAQ still hasn’t even touched its December 2019 lows.

All this as Friday marked the steepest single non-farm payroll drop anyone alive has ever seen. The US economy lost 701,000 jobs in March. A million Canadians have filed for unemployment, overwhelming the physical and digital infrastructure of what is suddenly the most vital government system outside of the healthcare sector. Entire industries are putting the lights out, and the only glimmer that we’ve seen of a light at the end of the shutdown tunnel, so far, was a poorly thought-out Presidential stab at rallying sentiment, universally ridiculed and since backed off.

Put it that way, and questions about whether or not these turns might be bottoms seem patently ridiculous. The question to ask about these markets isn’t “when will they get better?”, it’s “why aren’t they already much, much worse?”

…even if you’re not going to like the answers

The simplest answer is “denial.” Insomuch as stocks and bonds are constructs representing a consensus value of various businesses and the promises they’ve made to pay back what they’ve borrowed, the answer is that, for the time being, we still believe.

The best case scenario is that the economy turns back on like a switch, in short order, and investors desperately want to believe in that scenario. So, with the help of central bank liquidity, they’re choosing to believe in it. Conceivably, if the collective will to believe keeps up long enough, it could lead to an adjustment of baseline expectations that keeps equities in a numerical stasis of sorts. Investors who believe in growth will buy a stock out of a trough for fewer cents per share in earnings as long as they believe a recovery is on the way, but that isn’t going to float in the bond market.

“Will the Fed be able to restore order to the debt markets and, if so, what will that cost?”

Ever notice that “fixed income” literally translates to “a correction in revenue?”

The question US investment-grade corporate bond index LQD is trying to answer is “How committed the Fed is to saving corporate America?”

LQD was pricing in default risk on its first leg down, made up some ground with no small amount of help from the Fed, but the volume is flagging rapidly as price floats downward. It sure isn’t trading like a basket of bonds with the biggest backer. More like a basket of bonds whose yield is about to start taking the same beating from inflation as the bonds issued by the government that has pledged to back them.

We’ll print ourselves into oblivion before succumbing to socialism, comrade!

“To get the country through the pandemic, the US Government printed so much money that people had to carry it around on 1TB hard drives…”

-History books from 2097

The confidence meltdown hasn’t really got going yet, because the central banks at the center of this centrally planned market economy don’t yet seem worried or overwhelmed. And why should they be? They’ve been jamming fabricated money into this market for ages. Now they have to jam more in, and quicker. So what?

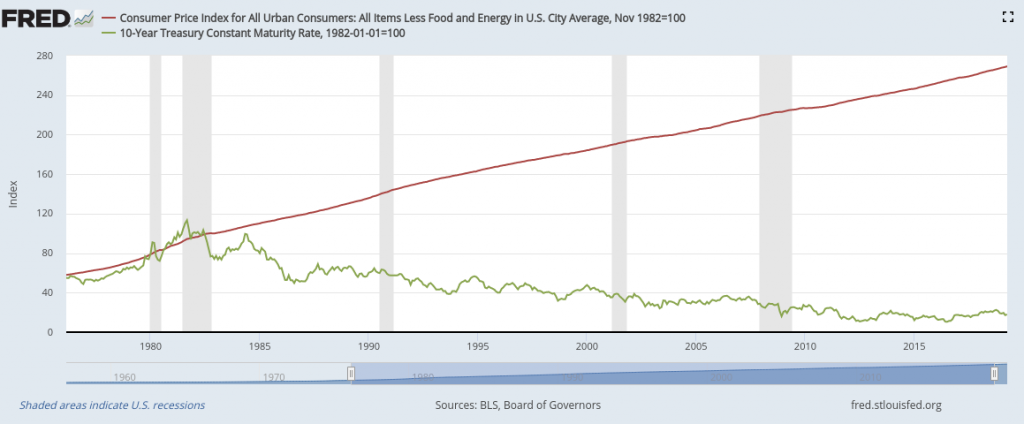

Smallcap Steve and others have identified hyperinflation as a potential result of these stimulus and liquidity measures and, as banks add monetary mass to make up for a lack of velocity, it becomes less of a risk and more of a certainty. Western governments, generally, have the assets and earning power to keep pace with a great deal of money creation, and the only real threat to that ability is a crippled economy, which used to seem preposterous and, so long as there remains a capable and willing workforce, still seems unlikely… But no longer feels impossible.

Inflation doesn’t bother debtors. Especially not long-term debtors. A dollar borrowed today can be paid back with an effectively “cheaper” dollar earned in the future. If inflation outpaces the interest rates, borrowers are making on the deal. Unless the borrower can’t earn to keep up with inflation, and that only happens to people who work for a living.

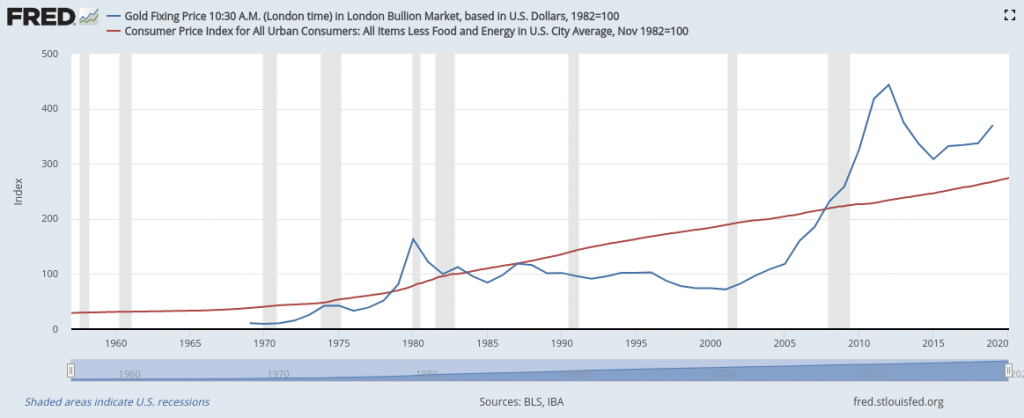

The inflationary writing on the wall is evident in the persistent strength of the gold market, and can be confirmed by the refusal (so far) of the bond markets to mount a convincing recovery.

“But what if I don’t want my money to lose its purchasing power?”

Investors should resist overthinking this. Gold is as much of an inflation hedge as it ever was, and it’s showing strength on the tail end of a recovery that didn’t get any help form the central bank… at least not directly.

Gold is subject to big swings, too, but we aren’t in this for a trade. We’re holding it to out-pace the printing press.

The expanded view shows gold failing to out-pace inflation for decades at a time, but those were quaint decades when much of the money was earning its way into the system by conventional means. If we zoom in a bit closer…

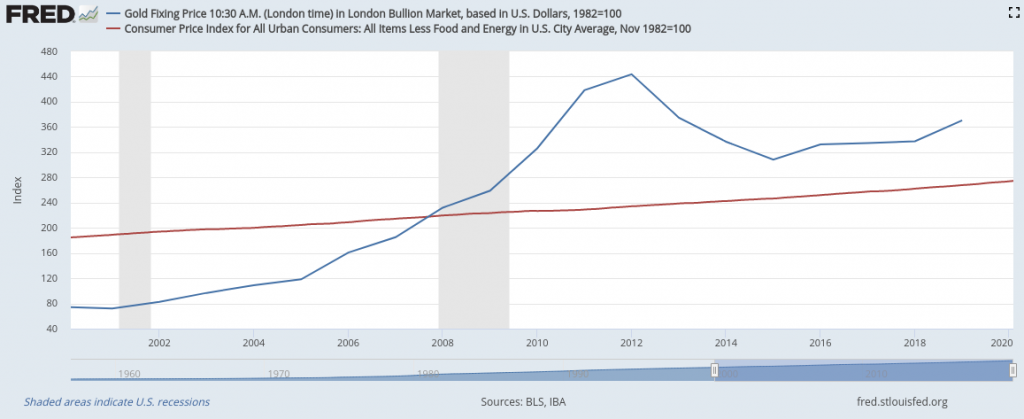

Gold crossed the CPI rubicon in October of 2007, just as the sub-prime mortgage markets started to un-wind, and really got going as the Fed printed their way out of that one.

We continue to build a defensive position out of cash and gold while both the real economy and its stock market proxy watch the bond markets nervously to decide whether to charge forward or fall apart. Stay tuned tomorrow, when we’ll look at the limited tools that we have for indicators of when that might be.