There’s no simple reason that Gamestop (NYSE: GME) became the subject of the most high-profile short squeeze anyone can remember. It’s one of those confluence-of-events types of scenarios where everything’s set up just so, and the setup is so widely followed that it takes on a life of its own. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. It’s best to start at the beginning, which isn’t complicated at all.

Prior to about two weeks ago, Gamestop the stock had more or less been a reflection of Gamestop the business, which had been sucking wind for quite some time. That made some very obvious sense, because Gamestop is a physical retailer of a product generally sold over the internet. Even before the pandemic made shopping malls a bio-hazard, consumers were done with Gamestop, which was best remembered for giving a trade-in value of around 3% on old games towards the purchase of new games. Notably, though, the people who complained about GameStop trade ins tended to complain about them a lot, indicating they went back.

This past August, as Gamestop the stock failed to keep up with a broader equities market that was heating up, former CEO of pet food e-retailer Chewy Inc. (NYSE: CHWY) and generic venture capital type guy Ryan Cohen started accumulating shares until he owned 12.9% of Gamestop. In November, he started what might be called an activist investor’s campaign, in which an investor buys a not-insignificant stake in a company, then makes a nuisance of themselves, publicly questioning management’s aptitude and agitating for control of the board of directors.

Sometimes, the activist investor pushes his fight for the hearts and minds of his fellow shareholders all the way to a proxy fight at the annual general meeting, but Gamestop didn’t put up much of a fight. Cohen was given three board seats on January 11th by a board of directors that seemed like it didn’t really know what it was going to do in the first place, and was happy to shirk responsibility to someone who seemed like he cared.

Enter Citron, Stage Left

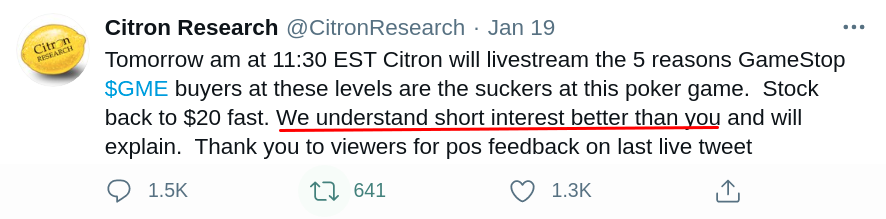

We aren’t aware of Citron Research having published a formal research report on Gamestop. If it did, it’s since been removed, making the sum-total of the material backing the firm’s short position a January 21st video. Within, Citron Research Founder and Executive Editor Andrew Left outlines the various reasons he’s short GME, prefacing it with an emphatic pronouncement that there is NOT a short squeeze in GME, so you can forget about it being a short squeeze, because a short squeeze isn’t what this is.

Left goes on to use various industry metrics and fundamental failings to illustrate the fact that Gamestop is a terrible business in the near term, rapidly losing market share and likely to lose more before the turnaround takes effect… but nobody has six minutes to listen to Left yammer on about stuff they already know. The part about this “absolutely NOT…” being a short squeeze for reasons that amount to, “I know it isn’t and I know more than you do!” was compelling. That part jumped right out and stuck.

Definition: Short Squeeze

The Short

Traders betting that a stock will go down in price borrow stock and sell it into the market. If they’re right, and the stock price does go down, they’re in a position to buy the shares they borrowed for cheaper than they sold the borrowed shares for, pay back the lender, and keep the difference. If they’re wrong, and the stock goes up, they may have to buy stock to cover the loan at a higher price, and lose money.

The Squeeze

When a stock that a lot of people are short starts to move up, and some of the shorts get nervous, they start buying to cover. The higher it goes, the more nervous they get, the more they feel like they have to cover before it runs some more. Shorts in a squeeze grab the offer, driving the price up and compounding the problem and, if it’s a stock with a lot of visibility… well… buying gets buying.

Enter Wall Street Bets

The degenerate gamblers over at the r/wallstreetbets subreddit have taken a lot of heat from market purists whose sensibilities were offended by their part in this Gamestop circus, none of which they deserved, because, as far as this column is concerned, Wall Street Bets is as pure as the driven snow when it comes to market motivations: they’re in it for the money.

Some of the more veteran players watched Andrew Left’s video and saw a guy betting that a stock would trade according to its fundamentals, and wondered if he was maybe acting more confident than he was, and might not have the mettle to stand pat if this thing went on a run. But the more animalistic elements of the forum just saw a smug jerk saying, “blah blah blah short squeeze, blah, blah, blah short squeeze,” and smelled blood.

Definition: Call Options

The right, but not the obligation, to buy a security at a predetermined price. Options trade on their own market and are sometimes used as a way to speculate on the short-term movements of the stocks they’re options to buy. Responsible short sellers use call options as a hedge against the trade falling apart on them.

For example, someone who has borrowed 1000 shares of GME and sold it short at $39.00 may also buy the OPTION to purchase 1000 shares of GME at $39.00 for $3/contract. If GSE runs to $50.00, the trader can exercise the option and pay the lender back with the stock received on exercise. The total loss (ignoring interest and commissions) would be $3,000 instead of $21,000. The hedge eats into profit, though, so shorts with conviction do not buy options to hedge.

The dice rollers down at r/wallstreetbets don’t have much use for hedges. To that crowd, options are used to gain exposure to the upward movement of expensive stocks without having to come up with the stake to have to buy the stock out of the market.

A gunslinger who thinks GME has some momentum and is going to go from $39 to the MOON can buy the call in hopes that the shares of GME that they have purchased the right to buy will be worth a lot more than $39 before the contract’s expiry date, and that he will be able to sell them for a profit. Right now, with Gamestop having closed at $76.79 yesterday, $39 GME calls expiring January 29th are trading at $42, representing a 1300% profit to a trader who bought them at $3.

Call and put options are created by market makers, who are ultimately responsible for delivery of the underlying securities should the option to purchase be exercised. Sometimes, the option is exercised and the stock is purchased, sometimes it isn’t, but a market maker always has to be ready to deliver when an option is “in the money,” and in danger of being exercised.

That means that some shlub on a market making desk somewhere in Chicago who put up 1000 GME call options at $39, then saw them get cleaned out with Gamestop on its way to $50 had to get his hands on 1000 shares of GME in case these ended up being exercised but… woah! They just took out the $55s?

Ultimately, the desks get a sense of which way the momentum is moving and just start writing option contracts as fast as the street will buy them, intentionally feeding the feedback loop, and letting the algos figure out what they’ll need for underlying.

It could be that some WSB traders had a sentimental attachment to Gamestop, or wanted to wipe the smug grin off that know-it-all Left’s face, or both. We can assure you that the primary driver of the bottomless appetite for GME call options that drove this epic rally was the compounding dopamine rush of a winning trade that had run away momentum. Cleaning out the options caused the market makers to have to fight for stock with shorts who were trying to cover, print a new high, then write more options, which stayed on the board about as long as a line of cocaine on a Coconut Grove coffee table.

GME closed at $61.50 on Friday, leaving twitter to buzz about these chuckleheads over on reddit making Gamestop come unglued from reality all weekend. Monday, with an even larger spotlight on the trade, GME blew its top at $159.18, eventually settling at $76.79.

Ryan Cohen’s $11.50 GME is looking like a pretty great buy. Whether he is more interested in making Gamestop into a more modern and successful enterprise or just taking the profit remains to be seen, but he should at least have some cash to try and make it work. The company hired a syndicate of banks this past December 8th to raise $100 million in an at-the-market offering, literally selling shares out of the company treasury into the market.

The coming post-pandemic world presumably being full of people craving socialization and human interaction, a games store with a strong brand could conceivably be coming up on a prime opportunity to re-invent itself; to host tournaments and fan-cons, and otherwise give the people what they want. Who knows, maybe it’ll write options on Warcraft gold and open up a trading floor.

Information for this briefing was found via Sedar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.

15 Responses

Nice post mate! Clear, credible and compelling reading. Thanks.

You should also touch on the idea that the markets as a whole have been leaving reality for some time and that this is just a symptom of a system that wasn’t designed for 2020 and onward. Stock markets are a relic today, and these are examples of it being inadequate for representing the economy at all. I think this is also driving the WSB folks.

You could also touch on the protests from a decade ago that brought up that the stock markets are tools for moneyed folks to make more. This kind of one-way trade halting from Robinhood et al. is an example of the “moneyed folks” not happy that another group has disrupted their activities and more importantly their profits. This can be seen as a protest and class warfare.

However, I understand your article was an attempt to explain the basics of the mechanics. BUT you also included speculation for motivations. If you’re going to do any of that, you should definitely look at it from as many perspectives as possible

Thanks for reading, Chris.

Going to let you in on a bit of inside-baseball here from the blogging biz. You see, if we try to cover something as enormous and broad as this trade, it’s place in popular culture, and its broader implications, then the posts get to be 5,000 words long before you know it, and nobody reads them. You may be interested a post published the next day about The Changing Financial Information Economy. I’m working on one right now about this story is making us come to terms with certain socio-economic realities that I think you’re going to LOVE, so stay tuned!

How can short interest of a company exceed 100 %?

Great question, Yannich!

The actual short interest in any stock at any given time is impossible to calculate. The “short interest” generally published by financial data providers is actually the number of shares loaned out, presumably to be sold short into the market, usually expressed as a percentage of the float. It could be >100% of the float because some shares have been loaned out more than once by the brokerage houses, because shares OUTSIDE of the float have also been loaned out, or just because the data isn’t very good.

There’s more about this in yesterday’s “Squeeze Play or Kayfabe” post.

Thanks for reading!

“That means that some shlub on a market making desk somewhere in Chicago who put up 1000 GME call options at $39, then saw them get cleaned out with Gamestop on its way to $50 had to get his hands on 1000 shares of GME”

Maybe you already know this, but 1 option contracts controls 100 shares, so if they sold 1000 call options, that means 100,000 shares needed to cover that. You meant 10 GME call options.

you also wrote:

“someone who has borrowed 1000 shares of GME and sold it short at $39.00 may also buy the OPTION to purchase 1000 shares of GME at $39.00 for $3/contract. […] would be $3,000 instead”

It’s not 3 dollar per contract, it’s per share. The contract is 300$. You buy 10 contracts to cover 1000 shares. the 3000$ figure is correct, so you do know how it works, there is just an error in nomenclature.

Thanks for reading, Frederic.

Since we’re most interested in explaining the concept in a way that gets it across our readers whose brains haven’t been warped by trading desks, we left lot-size out of the description to keep it simple. While we stand by the accuracy of our reporting, we don’t recommend anyone use The Deep Dive as a trading manual.

Or you could just fix your math errors and thank him for noting them.

I agree. That unthankful response sure told me something about the author. I’m a general everyday newbie trying to learn and also saw the error and got confused. Not so interested in reading anything further from the arrogant sort.

Thanks for reading, Erika!

Thank you for this, I thought I was nuts when the math didn’t add up.

We. Like. The. Stock.

Hi Braden. Really good article. Clear, well written and fun to read. (Former tech fund portfolio manager from back when GameStop went public in 2002)

Really GREAT article–I managed to be part of this squeeze and am now out

Thanks for reading, and congrats on the trade.

Stay tuned to The Dive, because there’s more where that came from.