Naturally, as long as it wants.

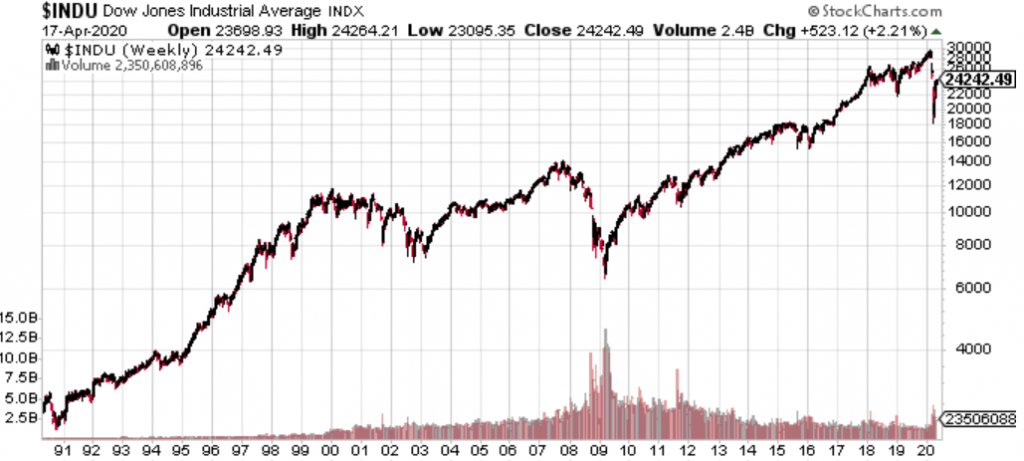

Despite constant assertions to the contrary, the stock market is not the economy. It’s a casino where people bet on the economy, mostly with other peoples’ money. The businesses that make up the pieces of that economy and the action on the casino floor aren’t worth much without the people who work at them, and use the money they earn to buy things from them.

Despite the fact that many of those people are presently locked in their house, working and buying at a reduced capacity, the odds-on bet in those casinos continues to be that the entities that form this economy and the debts they owe to each other will be just fine. Certainly, they’ll shut down a while but, with the help of government money and credit, they’re going to be able to pick back up where they left off. Like it’s no big deal.

Presently, the portion of those people who aren’t working from home or unemployed are using the opportunity of a recent (and long overdue) increase in their social standing and visibility to agitate for a larger share of the respective portions of the economy that they are operating.

Witness recent events in Staten Island, NY, where an Amazon warehouse mounted a walkout over a lack of personal protective equipment, only to have the walkout’s orchestrator fired at the earliest opportunity. Under normal conditions, the organizer would have been fired before he got a chance to rouse any rabble, indicating a pronounced slip in the company’s grip over its labour force.

While the COVID-Safety related complaints of workers are surely well founded, it’s difficult to imagine that the unskilled labour of the pre-COVID 2020 economy was at all happy with how things were going. They just couldn’t make it register, because they didn’t have the leverage.

Predictably, the stance taken by most of these larger employers has been to make a show of very basic concessions – more liberal sick-leave policies, reasonable scheduling, etc. – because the conditions don’t leave much choice.

It’s no coincidence that this unrest is manifesting itself at the larger companies whose continued operation is presently vital. Bloomberg getting through the whole segment without mentioning the U-word felt like a deliberate ignoring of the true and sustained threat to these bottom lines – as though they’re afraid to confront it and make everything all awkward.

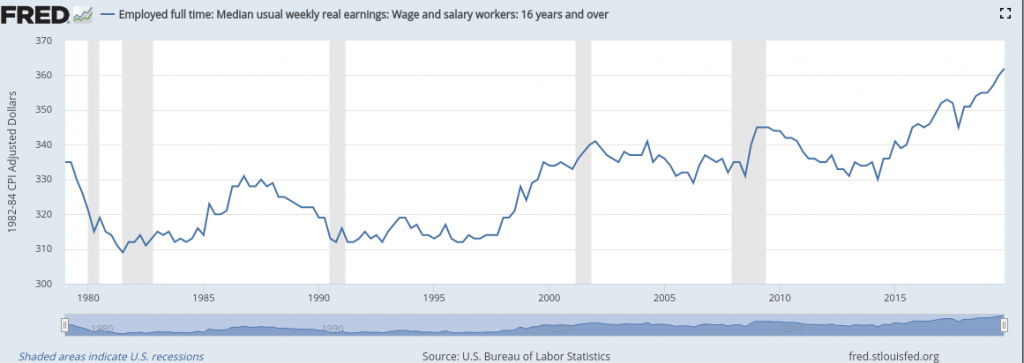

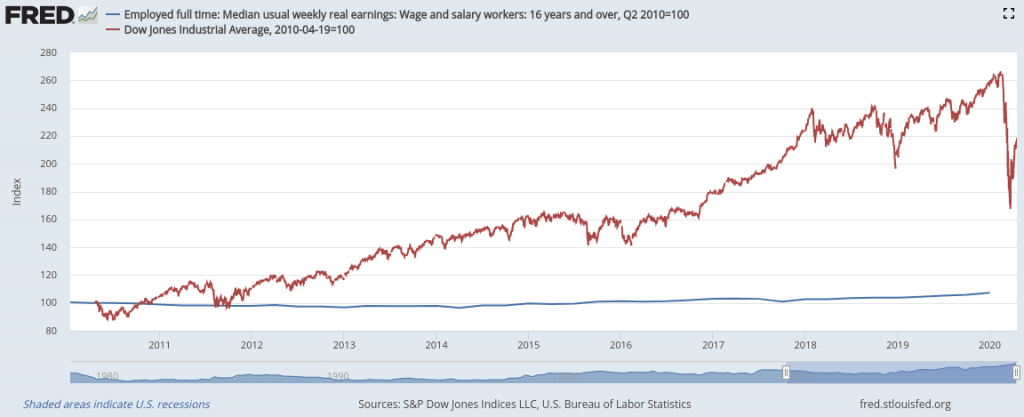

Federal Reserve tracking of BLS Real Wages Statistics have those wages growing 13% since 1990, from $319/ week to $362/week.

The Dow growing 8868% over that same period is no coincidence. Growth that is invested in the labour force isn’t much use to investors, who would much rather it went towards dividends, buybacks and expanding the footprint of the business. Unskilled labour that doesn’t have the leverage of collective strike action is replaceable, and increasing corporate influence over political infrastructure throughout the 1980s and 1990s saw a systematic and international erosion of workers’ rights to organize and act as collectives.

Elected officials and people seeking office adopted a narrative about policies that were “business friendly” and would “create jobs,” or “bring jobs back.” Policies designed to improve wages, reduce cost of living or mandate benefits were unheard of. It would be popular with voters, sure, but what good was that if it tuned off donors?

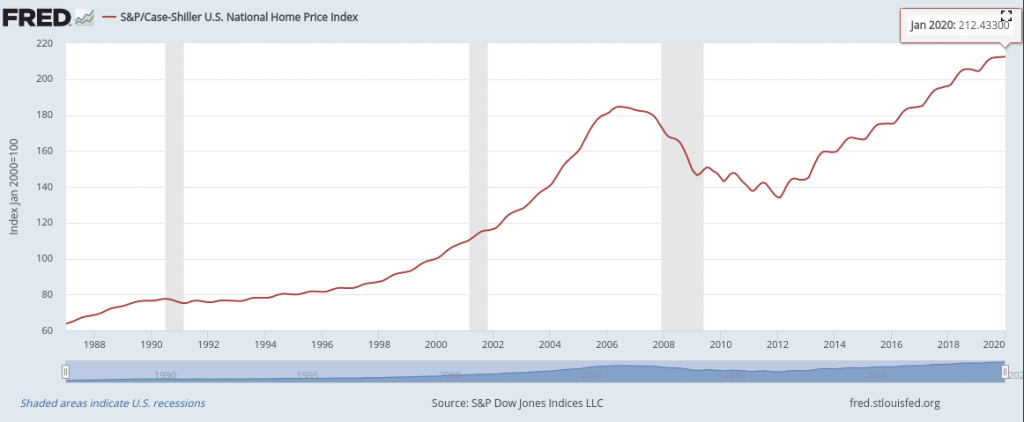

This seemingly unsustainable condition was partially bootstrapped by folding the wage-earning class into the investor class. The alchemy of lending and securitized debt managed to make a great deal of the nation’s savings into a leveraged bet on the housing market. Real-Estate as a primary business was an easy sell to anyone who understood the importance of a roof over heir head. The income side of someone else’s rent expense sounds like the closest thing there is to a sure thing.

An over-securitization of that “sure thing” showed its weakness in 2008, was patched up by central banks, and is presently reckoning with the very real possibility that the rent isn’t all that sure of a thing when wage earners responsible for either their mortgage or someone else’s have had their earning power hollowed out.

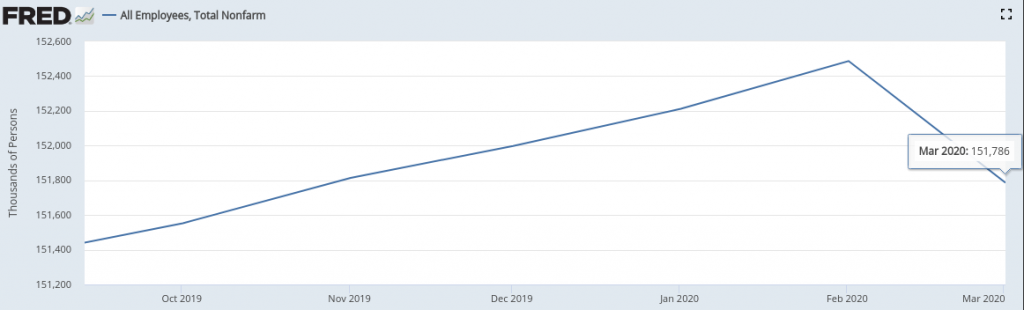

Whether or not the eventual recovery will be prolonged by management and labour failing to get on the same page until such a recovery has a chance to begin is unknown. But the present, effectively comatose state of the actual economy, the people who still have jobs aren’t showing the type of gratitude that their employers would sure like to see in an environment of rampant joblessness: they’re pissed.

We wrote last week about how a record-high volatility index is a reflection of the turmoil in the COVID-Era capital markets. They don’t know which way they want to break. Wider sentiment seems to have come around to a shakey belief in central banking’s ability to float this securitized mess of an economy, but in the context of a labour movement gaining critical mass, that turmoil may take a decisive turn downward as the real economy doesn’t preform the way investors hope as it comes out of its stasis. We’ve learned the hard way that, while markets are imperfect proxies, they’re always trying to tell us something.

The uncertainty being expressed with this record volatility includes the uncertainty that these businesses will be able to get as much as they have been out of a labour force suddenly waking up to the leverage it has as a collective.

The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.