Canada’s supply management regime—originally conceived to stabilize volatile agricultural markets—has calcified into an anti-competitive fortress. In a piece by Dr. Stuart Smyth, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of Saskatchewan, he described how this system “harms all Canadians thanks to the artificially inflated prices we pay for these products.”

As tariff walls reach nearly 300%, quota constraints force producers to dump good milk by the billions of litres, and trade negotiators find their hands tied, the case for dismantling this relic has never been stronger.

In the early 1970s, volatile commodity prices and communication lags left dairy, egg and poultry producers vulnerable to ruinous swings. Ottawa’s answer was supply management: a combination of production quotas, administered under the Farm Products Marketing Agencies Act, and steep import barriers once small tariff-free volumes were exhausted.

Dairy quotas began in 1970; eggs followed in 1972; poultry products were folded in by 1978 and 1986. By controlling “annual production levels for each commodity,” the system traded free-market discipline for price stability.

Economic inefficiencies

Yet today’s economic landscape could not be more different. Inflation has sat below 2% since the 1990s, and instantaneous global markets have largely tamed the price shocks of yesteryear.

Despite these changes, supply management “remains in place despite the current absence of many of the economic factors that spurred its original implementation.”

Canada’s quota formula, apportioned by provincial population, has warped production geography. Prairie provinces—where the average herd ranges from 183 to 194 cows—account for just 16% of national milk output, while Quebec, with herds averaging 83 cows, commands 37%. In a true free market, herd sizes and processing facilities would gravitate toward efficiencies; instead, quota keeps economic activity anchored in less productive regions.

The human cost of that inefficiency is stark. Between 2012 and 2024, 6.8 billion litres of milk—worth nearly $15 billion—were dumped because producers “could not sell it to consumers at a lower price.” That volume could have nourished 4.2 million people every year. Wasted water, feed and the greenhouse gases emitted in producing discarded milk compound an environmental tragedy atop an economic one.

Remember that video of a worker in a Southern Ontario dairy farm that trended because he had to dump around 30,000 litres of milk because they were in excess of their quota? The worker said he had no other option because the regulators are making them dump the excess milk, which was incredulous at that time when milk retails for as much as $7 per liter.

The tariff fortress

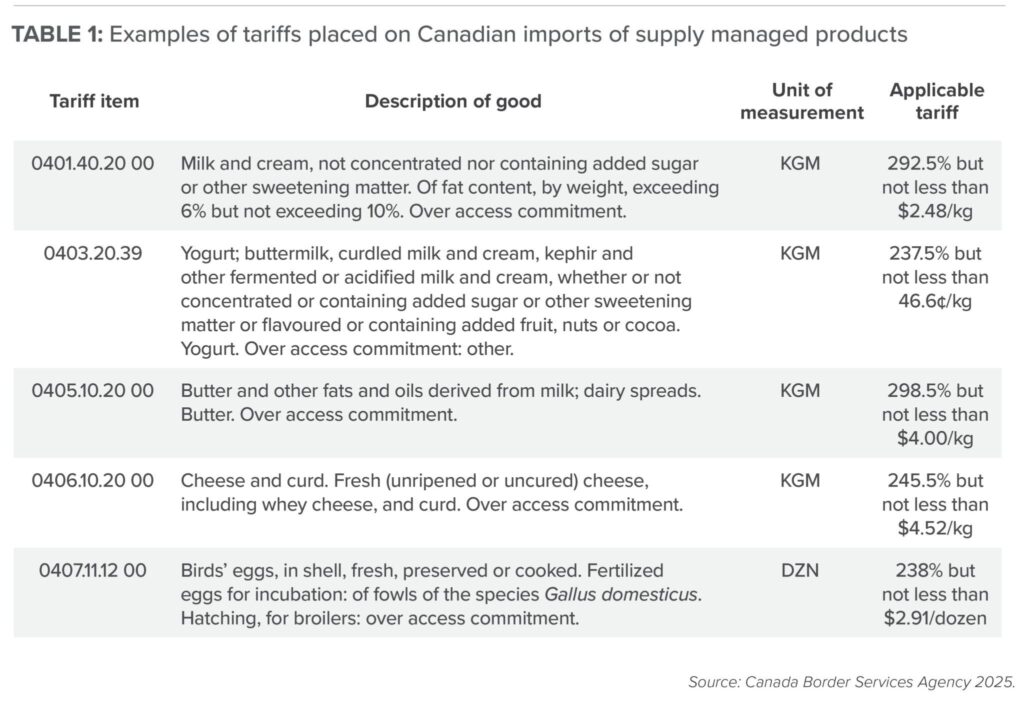

Once Canada’s modest tariff-free import commitments are filled, foreign dairy, egg and poultry products face duties that often exceed 200%, with per-unit minimums as high as $4.52 per kg for cheese and $2.48 per kg for milk. Butter bears a 298.5% levy (minimum $4.00 per kg); yogurt and fermented milks face 237.5% (minimum $0.466 per kg); table eggs incur 238% (minimum $2.91 per dozen).

These rates—drawn from Canada Border Services Agency data—effectively shut out competition and leave Canadians paying the premium.

Canada’s stubborn protectionism in supply-managed sectors has hamstrung its ability to strike new trade deals. During the Trans-Pacific Partnership talks, Ottawa reluctantly conceded 3.25% tariff-free dairy access to secure broader market openings.

Under CETA and USMCA, further carve-outs followed, each met with billions of dollars in compensation to domestic farmers. Meanwhile, beef, pork and grain exporters gain no such relief when foreign products undercut Canadian prices.

The result: Canada pays the price in agricultural diplomacy every time it knocks on another country’s door.

Higher prices hit lower-income households hardest. Pre-pandemic estimates placed the annual cost of supply management at $300–444 per household—funds that could instead cover essentials or foster healthier diets.

Frequent mandatory price hikes exacerbate the strain: families on fixed incomes struggle to afford milk and eggs, jeopardizing child nutrition and long-term health. Meanwhile, with global food insecurity on the rise—a looming 30-million-tonne dairy shortfall by 2030—Canada’s hoarded production capacity could otherwise bolster international relief efforts and help meet UN Sustainable Development Goals.

A roadmap to freedom

Under the WTO’s 1995 Agreement on Agriculture—negotiated during the Uruguay Round—member countries committed to three pillars designed to liberalize farm trade: cutting trade-distorting domestic supports (the “amber-box”) by prescribed percentages, converting non-tariff barriers into bound tariffs with accompanying tariff-rate quotas to guarantee minimum market access, and phasing down export subsidies both in value and volume.

Since the WTO’s 1995 rules took effect, Canada’s supply‐managed sectors have resisted full compliance. Unlike other nations that have eliminated production subsidies and seen benefits for both farmers and consumers, Canada has maintained its subsidy regime for the past three decades.

Australia deregulated milk in 2000. Over the following two decades, consumers enjoyed a 12-cent per-litre price drop, while farmers saw their farmgate returns rise. Today, Australian producers export nearly half their milk production, fueling jobs and economic growth. That experience demonstrates a managed transition can benefit both sides of the farm gate.

Phasing out supply management over ten years—with 10% annual cuts to quotas and tariffs—would give producers time to adapt, suggested Smyth. He puts that policymakers should enable nationwide trading of quota licences, allowing smaller Quebec operators to sell to larger Prairie herds at fair market value.

The government should also offer a time-limited backstop for farmers who used quota as loan collateral, preventing bank calls as quota values decline.

Lastly, they should also guarantee a 10-year bridge to help young farmers retain equity and invest in efficiency upgrades.

Such policies smooth the transition, minimize economic disruption and liberate Canadian agriculture to innovate and compete without artificial shackles.

Smyth admits that some smaller supply-managed farms may not survive a shift to a freer market but he says this is a tough but necessary process that all agricultural sectors undergo. As less efficient operations exit, more competitive producers will step in, maintaining stable supply and preventing shortages without the need for forced price hikes.

By lifting quota and tariff restrictions, new and existing farmers can expand or enter the dairy, egg, and poultry markets, driving down costs and fostering innovation. This expanded production will not only stabilize prices but also generate jobs both on the farm and in value-added facilities like cheese and yogurt plants.

Canadian consumers deserve more choice and lower bills, and only by retiring supply management can governments pave the way for a truly competitive, resilient, and prosperous agricultural industry.

Information for this briefing was found via Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.