Max Resource Corp (TSX-V:MXR) saw a 25% gain in its share price Wednesday, as investors digested the latest news from the company’s Cesar copper+silver project in northeastern Colombia.

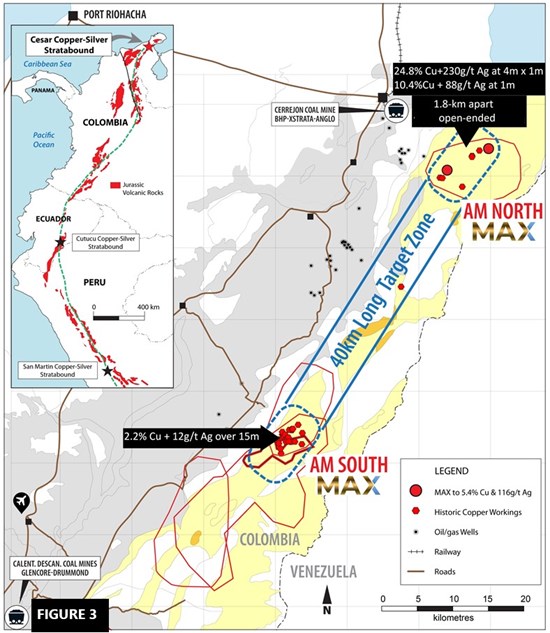

A week after publication of two significant stratabound discoveries at a new zone called “AM North”, 40 km north of its recent AM South discovery, field crews found a high-grade outcrop featuring 24.8% copper and 230 grams per tonne silver.

Rock that – at todays copper price of US$2.57 and silvers price of US$17.30 – is valued at an amazing US$1,533.14 per tonne (Fig 1).

AM North contains two mineralized areas from which rock samples were taken – AMN-1 and AMN-2. Both zones dip 20 degrees northwest and appear to be part of the same mineralized horizon.

The assays published in the March 4 news release were taken from a 4m by 1m rock chip panel, found along a 1.8km strike zone Max has identified through previous rock chip sampling.

This article was originally published at AheadoftheHerd.com. The original work can be found here.

“We were pleasantly surprised that the AM North discovery was made in just a one-day field reconnaissance. Given the early stage success at both, AM North and AM South, we are confident in further exploration successes in 2020,” said Max’s CEO, Brett Matich. He qualified the high-grade results by saying the company is working on the premise of an average target grade of +1.5% copper with associated silver.

Since November, Max’s geological teams and prospectors have been identifying copper+silver targets in the 120 km x 20 km target area at Cesar, using rock chip sampling to identify structures, continuity of thickness, and strike length, to determine potential size prior to drilling.

The company is following the theory that continuous rock chip samples are pointing to a giant sediment-hosted copper+silver mineralized system.

In the Feb. 27 news release, Max notes that AM North and AM South are both hosted in well-bedded sandstone-siltstone similar to KGHM’s monster “Kupferschiefer” deposit in Poland.

In an earlier interview with AOTH, Max’s head geologist, Piotr Lutynski, said Colombia’s stratigraphy is similar to his homeland, Poland, and its cluster of Kupferschiefer sediment-hosted copper-silver deposits.

In 2018 KGHM Polska Miedź (KGHM), the only copper producer in Poland, mined 30.252 million tonnes of ore at 1.49% copper (Cu) and 48.6 g/t silver (Ag), comprising 452,000t of Cu and 47.2 million ounces of silver. The amount of copper and silver production decreased by a respective 2.99% and 1.28%, compared to 2017.

Other metals recovered from copper ores at Poland’s Kupferschiefer deposits include gold, platinum, palladium and renium.

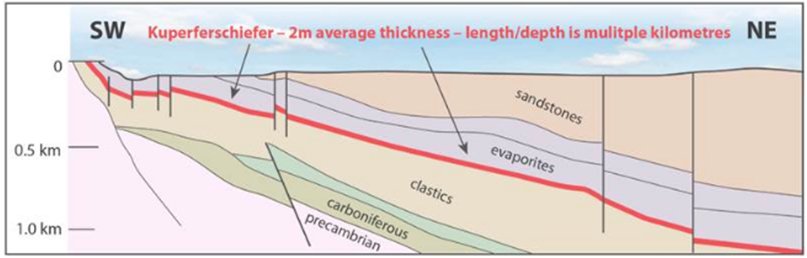

According to the US Geological Survey, the massive volume of metal in Poland’s Kupferschiefer deposits is due to continuous mineralization that extends down dip and laterally for kilometers (Fig 3). Max cautions investors that the mineralization at Cesar is not necessarily indicative of similar mineralization in Poland.

To understand the significance of the Kupferschiefer analogy, we need to take a brief detour into the geology.

Sedimentary copper deposits

The exploration targets Max is identifying at Cesar are characterized as sediment-hosted copper and silver. The mineralization is comparable to a specific type of sedimentary copper + silver deposit called a “Kupferschiefer” which means copper shale in German.

Sedimentary-hosted stratiform copper deposits are among the two most important copper sources in the world, the other being copper porphyries. They typically range from 1.6 million to 170 million tonnes copper ore, grading between 0.7% and 4.2%, with a median of 14 million tonnes at an average grade of 1.6% Cu, according to a 2019 academic paper, ‘The Kupferschiefer Deposits and Prospects in SW Poland: Past, Present and Future’.

Sedimentary copper deposits are formed in ocean basins, where the seabed is composed of porous materials such as sandstone, limestone and black shale, through which copper and other minerals travel up and become trapped in the rock layers.

The process of mineral deposition is quite different from a copper porphyry deposit, which is formed when a block of molten-rock magma cools. The cooling leads to a separation of dissolved metals into distinct zones, resulting in rich deposits of copper, molybdenum, gold, tin, zinc and lead. A porphyry is defined as a large mass of mineralized igneous rock, consisting of large-grained crystals such as quartz and feldspar, that is often suitable for bulk mining.

Sedimentary exhalative deposits formed when hydrothermal fluids contacted a body of water, and precipitated ore. The large deposits in the Zambian copper belt are an example of SedEx-style mineralization.

Red-bed deposits, so named due to oxidation resulting from exposure to the atmosphere, are divided into volcanic and sedimentary.

Kupferschiefer comparison

Kupferschiefer deposits are similar to red-beds but larger, even regionally extensive. They typically form in a marine setting, after land is gradually submerged into a shallow sea, then overlain by sedimentary rocks – which formed from the gradual deposition of the carcasses of dead sea creatures, onto the ocean floor.

The Kupferschiefer copper belt that underlies Germany and Poland is among only three “supergiant” sediment-hosted copper deposits in the world. It is also within an elite 1% of deposits that contain over 60 million tonnes of copper.

A classic Kupferschiefer consists of three main layers – sandstone, bituminous shale and limestone overlain by evaporates often containing oil and gas. Copper-containing fluids migrate up through the sandstone and get trapped by the carbon-rich copper shale. This is where most of the mineralization is concentrated, although it can also be found in the sandstone, limestone, or a combination of all three layers.

One of the best examples of Kupferschiefer sediment-hosted copper mineralization is a 60 km-wide by 20-km belt in Poland, which extends from Lubin in the southeast to Bytom Odrzański in the northwest (Fig 4).

The strongest copper sulfide mineralization occurs in the black clay shales, including chalcocite, bornite, covelline and chalcopyrite, accompanied by minerals associated with silver, native silver, lead, zinc, cobalt and nickel.

It’s interesting to note that the Kupferschiefer in Poland is the biggest deposit of cobalt in Europe, but it is not currently being mined.

Ore from three underground mines – Lubin, Polkowice-Sieroszowice and Rudna – is extracted using the room and pillar method at depths of between 600 and 1,250 meters.

The earliest exploration dates back to 1914, when German geologists conducted studies of the Zlotoryja region, and later, Grodziec. The first mine, Lena, started in 1936 but production was halted due to the onset of World War Two.

In 1959, 24 drill holes outlined the Lubin-Sieroszowice deposit, found at depths of between 400 and 1,000 meters. A resource estimate tallied indicated resources of 1.364 billion tonnes of ore grading 1.42%, containing 19.34 million tonnes of copper and about 1.157 billion ounces of silver.

Copper mining began in 1968 with the commissioning of two mines, Lubin and Polkowice.

Today, the giant Lubin-Sieroszowice deposit contains 52 million tonnes of copper and 2.275 billion ounces of silver, at an average thickness of 3.58m containing 1.99% Cu and 47 grams per tonne silver. These are high grades. In British Columbia’s copper-gold country, copper grades average 0.4%.

Compare the close to 2% Cu to the grades being found at Cesar – up to 10.4% Cu and 88 g/t silver at the AM-1 discovery, and 24.8% Cu + 230 g/t silver at AM-2.

Of course, extreme caution is advised when comparing one project’s assays to another, but I consider Max’s results from AM North to be outstanding copper and silver grades. Also – these grades are averages from panels, not pieces of high-grade ore chipped from the outcrop to fool investors into thinking the whole outcrop is high-grade when only a small chunk of it is. It’s important for investors to differentiate between a select rock chip sample, and average grade across a 3m x 3m = 9 square meter panel.

This is an important distinction.

In the schematic below, notice the stratified nature of the Lubin deposit, with the black “Kupferschiefer” layer sandwiched in-between the multi-colored rock layers including sandstone and limestone. The black and white diagram at the upper right shows the U-shaped deposit characterized by columns of mineralization; each column consists of a thin layer of copper shale locked between the sandstone and the limestone, visualized here as a stack of books or a brick chimney (Fig 5).

Outlining a porphyry copper deposit is difficult and expensive because so much drilling has to be done to figure out what is the size and shape of the deposit. With sedimentary copper, the trick is to find the copper outcroppings, then find the orebody that may be dipping beneath the soil cover. After that, it’s a matter of identifying the best drill targets.

Max’s goal is to get to that point, bring in a major copper company as a partner, that can help finance a drill program at Cesar and bring it to a resource, then complete the rest of the steps (PEA, prefeasibility study, feasibility study, permits, etc.) required to build a mine.

At AOTH, we are pleased to see Max hitting such high grades at Cesar, and that the company has identified a 40-km target zone defined, so far, by AM North and South. We are very interested to see whether enough copper and silver showings, at significant grades, can be identified along that 40-km zone to call it a mineralized trend.

Max has only been working the Cesar property since November but already we are seeing consistently positive news flow, which the market is rewarding. Keep your dial tuned to Ahead of the Herd for more updates from Max Resource Corp.

Content sourced via Ahead of the Herd, written by Richard (Rick) Mills. Full disclaimer associated with this work can be found at AheadoftheHerd.com.

The Deep Dive, and it’s parent company Canacom Group, has not reviewed the above content and is hereby not responsible for statements made within. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The Deep Dive and it’s parent company Canacom Group holds no licenses.

FULL DISCLOSURE: Max Resource Corp is a client of Canacom Group, the parent company of The Deep Dive. The author has been compensated to cover Max Resource Corp on The Deep Dive, with The Deep Dive having full editorial control. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security.