The repercussions from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continue to broaden and deepen. The prices of some of the world’s important commodities such as oil, natural gas, fertilizers, nickel, and copper have soared as future production levels of those materials (that the West will still accept from Russia) have come into question. In addition, and somewhat surprisingly, the conflict may greatly affect an industry — semiconductor manufacturing — that is generally not associated with either Russia or Ukraine.

Ukraine produces about half of the world’s neon gas, and most of that gas is shipped to the U.S. to be utilized in its semiconductor industry. The neon produced by Ukraine starts as a byproduct of steel production in Russia and is refined to 99.99% purity levels at facilities in Ukraine. Much of Ukraine’s neon production is centered around the port city of Odessa, where the fighting is expected to begin at any moment. To state the obvious, Ukraine companies currently face enormous obstacles in attempting both to produce neon gas in and to export it from these facilities.

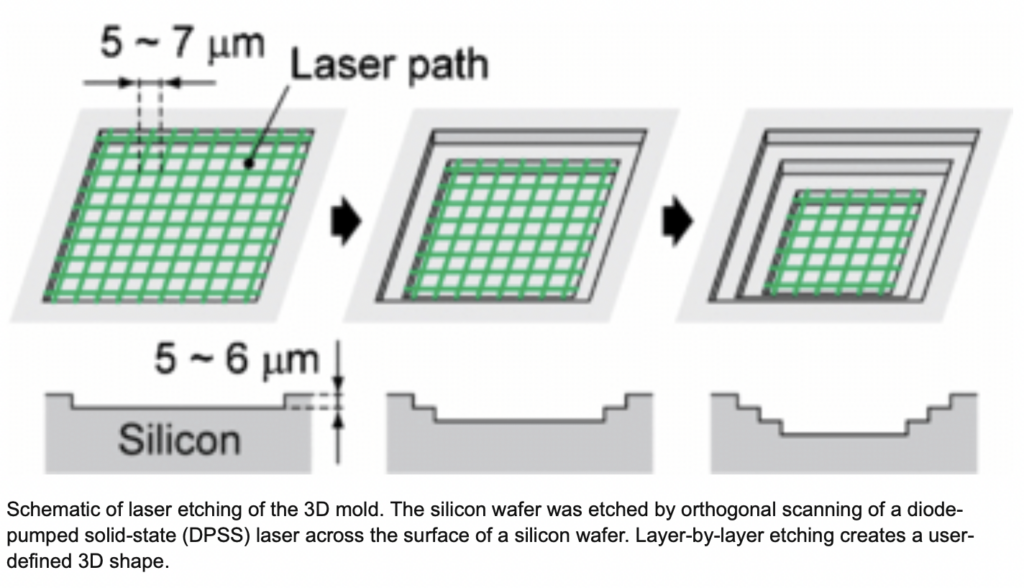

In the chip industry, neon gas powers lasers that etch patterns into individual chips. Etching removes layers from the surface of a wafer during manufacturing; each wafer typically goes through many etching steps.

Some industry analysts contend that no other gas can effectively replace neon in this role. Even more concerning: an analyst at TechCet, an electronic materials advisory firm which advises large chip makers like Intel, contends that U.S.-based semiconductor manufacturers source 80%-90% of their neon imports from Ukraine.

The implication of all this is that reduced neon availability from Ukraine could prove to limit chip industry production levels. Furthermore, this new impediment would come at a time when the industry is struggling to satisfy enormous global post-pandemic demand for semiconductors, which are the brains of devices from automobiles to smartphones. In turn, high-value products, like highly-awaited new electric vehicle models, could face further production delays.

Clearly, the chip industry in time will be able to source neon gas from other locations, but that switch cannot be made immediately. Reportedly, certification of new facilities can take several months. The leader of Daito Medical Gas, a pressurized gas dealer in Japan, neatly sums up the current situation in a quote to a reporter from the Financial Times: “We are in great trouble. We have no rare gases to sell.”

Some chipmakers, like the giant memory chipmakers Samsung and SK Hynix, either have neon gas plants located in China or have contracted for neon gas supply with Chinese plants and would appear to be insulated from any neon gas shortage.

Interestingly, a similar neon sourcing problem occurred in 2014 when Russia invaded Crimea. Then, neon prices spiked 600% or more, but prices fairly quickly reversed back to around original price levels. However, the 2014 Crimea conflict was both less severe by orders of magnitude than the Russia-Ukraine war and was accompanied by far less worldwide outrage.

Today, neon prices have at least tripled, but that gain likely is not an accurate gauge of the scope of the problem. Most neon gas transactions are done via long-term contracts.

Information for this briefing was found via Edgar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Views expressed within are solely that of the author. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.