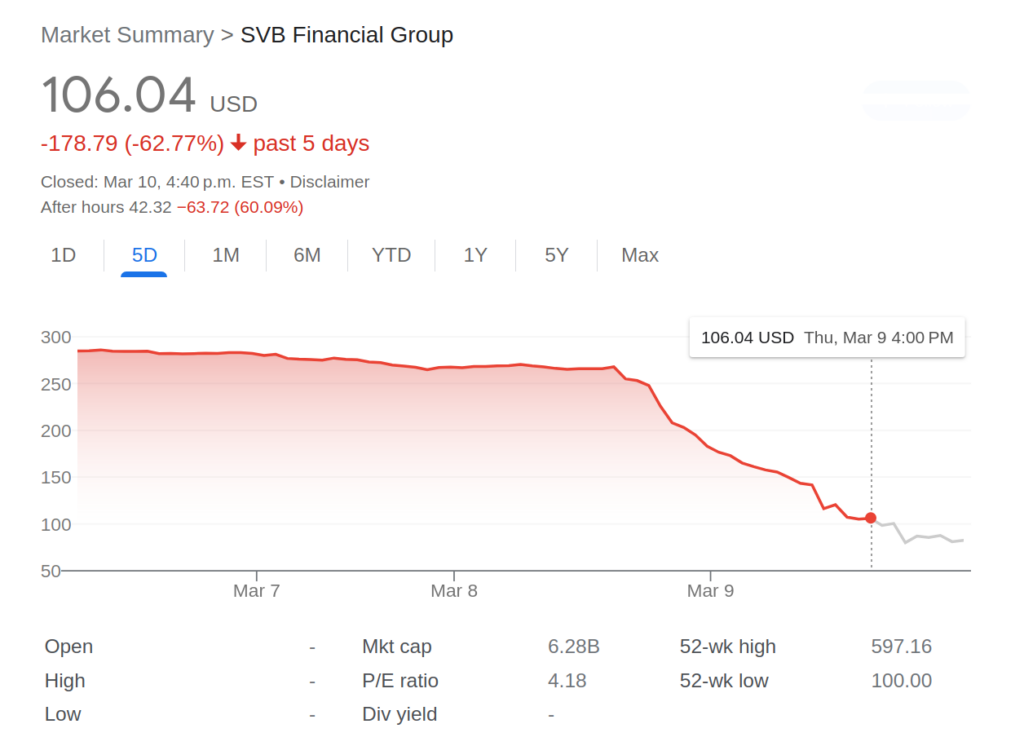

The US banking sector was staggered last week in a reaction to SVB Financial Group (NASDAQ: SIVB), the parent company of Silicon Valley Bank, a California banking enterprise that is exactly what it sounds like, briefly flailing about looking for a liquidity injection, before ultimately entering receivership Friday.

The market first caught The Fear when SVB filed a prospectus for a lousy $1.75 billion equity offering, which was meant to come in ahead of a $500 million order from private equity firm General Atlantic. The prospectus seems unremarkable at first glance, but GA’s commitment being contingent on full subscription of the rest of the offering might have been the first sign of trouble.

It’s a BANK. With a $211 billion balance sheet, a $28 billion enterprise value, and capital ratios all within the tolerances required by the Federal Reserve and state regulators. It’s used to going to the market every once in a while to raise a few bucks. Those raises never even makes the news, let alone cause the banking index to implode.

No single fire… just lots of smaller fires.

Cash fires.

But the amount of money in the raise isn’t as important as the reason they needed it. The prospectus went on to disclose that SVB had sold “substantially all” of its available-for-sale securities Wednesday to create $21 billion in cash. They were bank-reserve-type securities; treasury bills and government-backed mortgage paper and such.

Bonds that were issued before rates went up are worth less money now, than they were when they were purchased. Selling them instead of holding them generated a $1.8 billion dollar loss, so the bank went to the equity market to plug the hole. What’s the big deal?

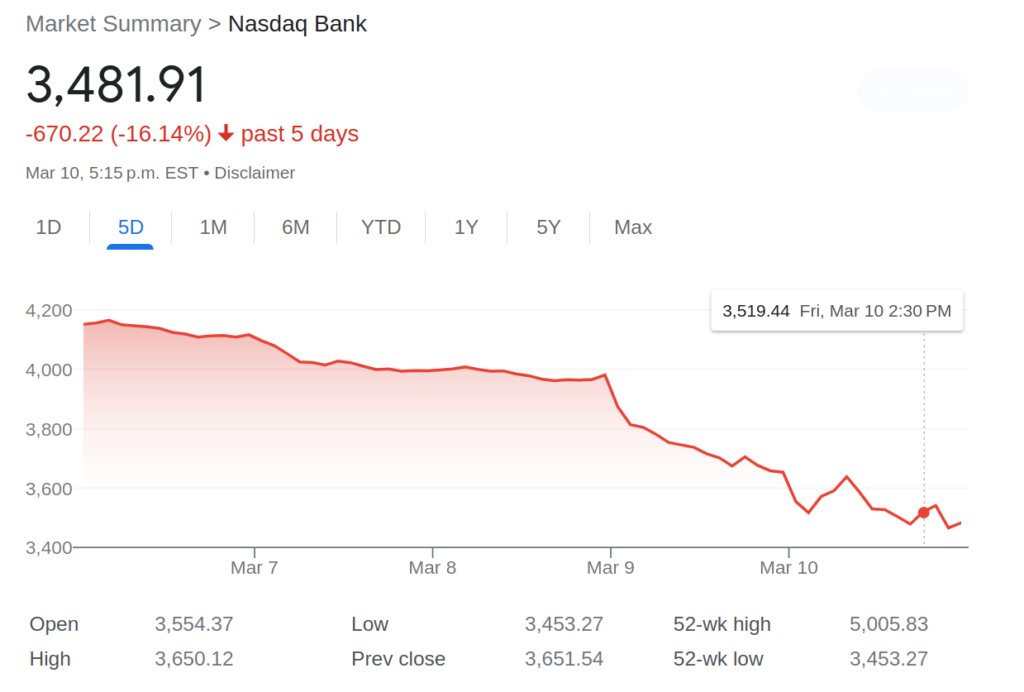

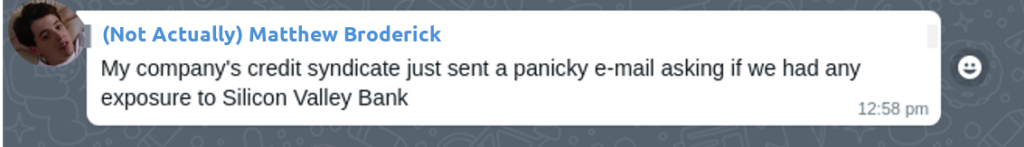

The big deal is that it needed the $21 billion in the first place. 10% of total assets is a lot of cash to have to come up with all at once, and it had the market wondering if the liquidity problems being telegraphed by SVB might be a symptom of a disease it picked up from the broader banking environment.

This first in a two part series will chart the specific jam SVB put itself in.

Make sure to check out What Happened at SVB? for a detailed look at the enterprise-level problems that got them here, and sound off in the comments to let us know if you think this could get contagious.

Charting the SVB Collapse

The core of Silicon Valley Financial Group is Silicon Valley Bank; a FDIC-insured bank that is supervised and regulated by the Federal Reserve. Banks in that class all do some version of the same thing: take deposits from customers, and make loans to customers at a higher rate of interest than it’s paying on the deposits.

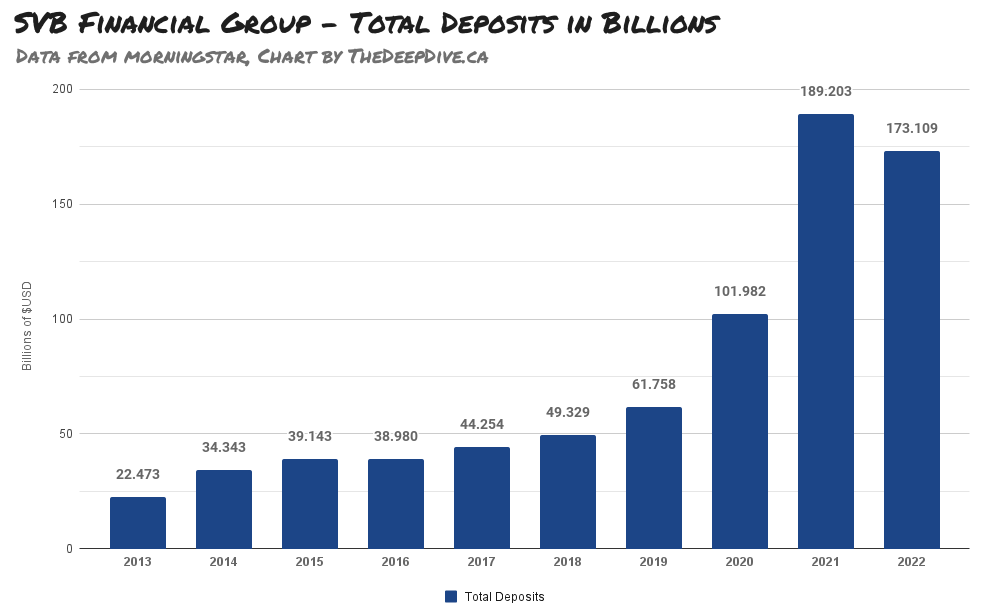

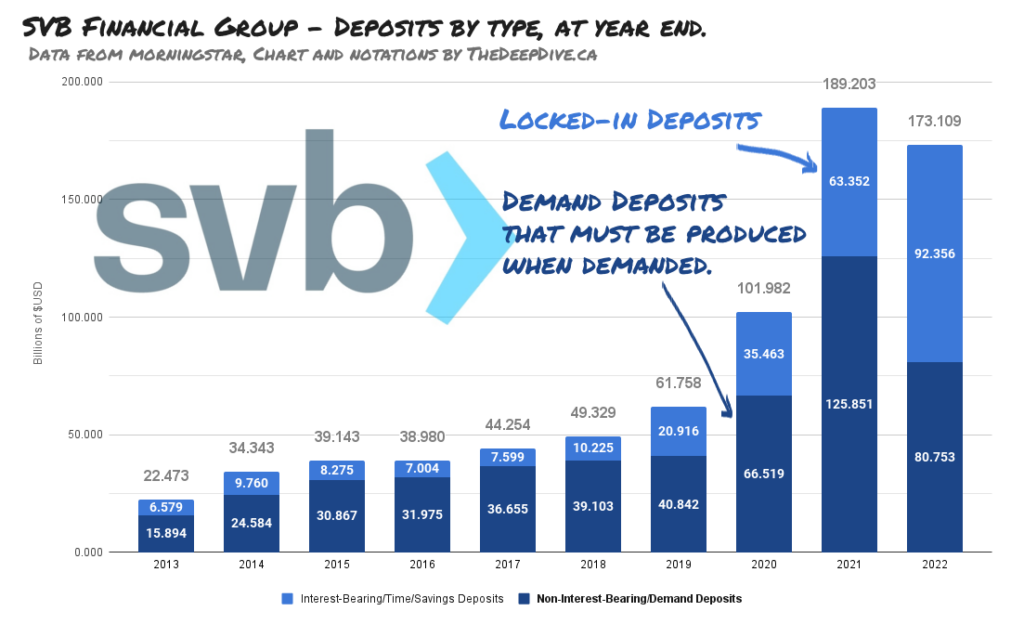

This is a chart of Silicon Valley Bank’s total deposits, at year end. Pretty good chunk of money. The spike in 2021 came after SVB acquired Boston Private Financial Holdings, and a bit of leveling off the next year is to be expected.

Deposits are a double edged sword. The bank can use them to make loans, so long as – between the cash in the vault and new deposits – they’ve always got enough in the vault to satisfy the withdrawals.

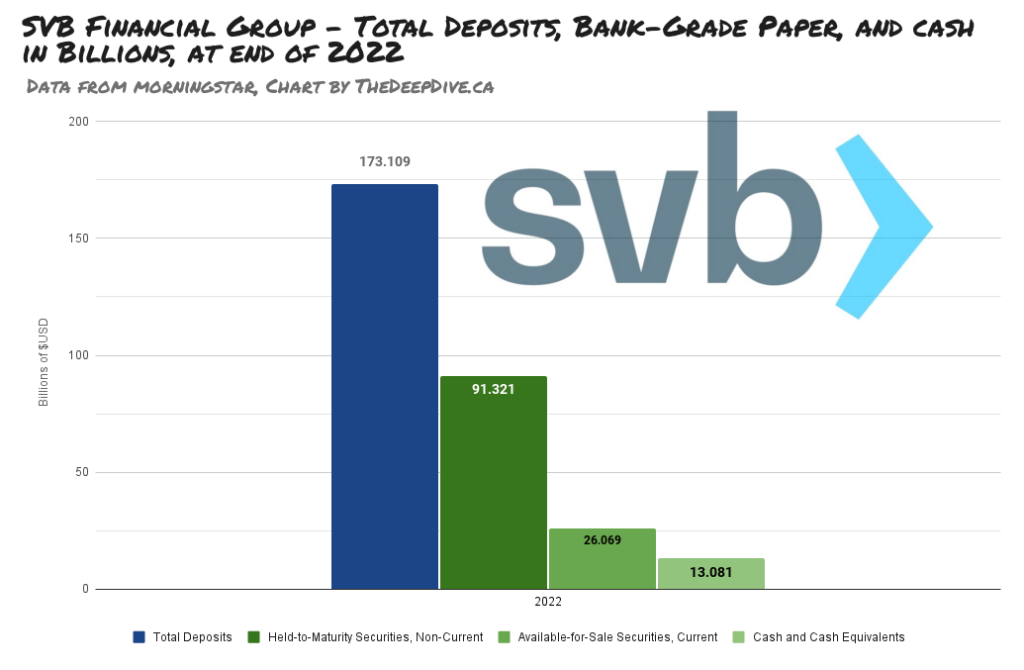

To be able to take those deposits, the rules say, the bank has to keep a certain amount of liquid reserves. Generally, those reserves are kept in approved government paper that doesn’t fluctuate much in price, and can be sold if it needs to be. Pre-collapse SVB held various kinds of safe, boring stuff that paid a return so reliable and steady it might put you to sleep. Fine, high-grade banking reserve paper.

That paper comes in two categories: available for sale (AFS) and held to maturity (HTM). They’re all the same types of bonds, the bank just keeps the ones that it will sell if it needs to in another category. Silicon Valley also had $13 billion in cash.

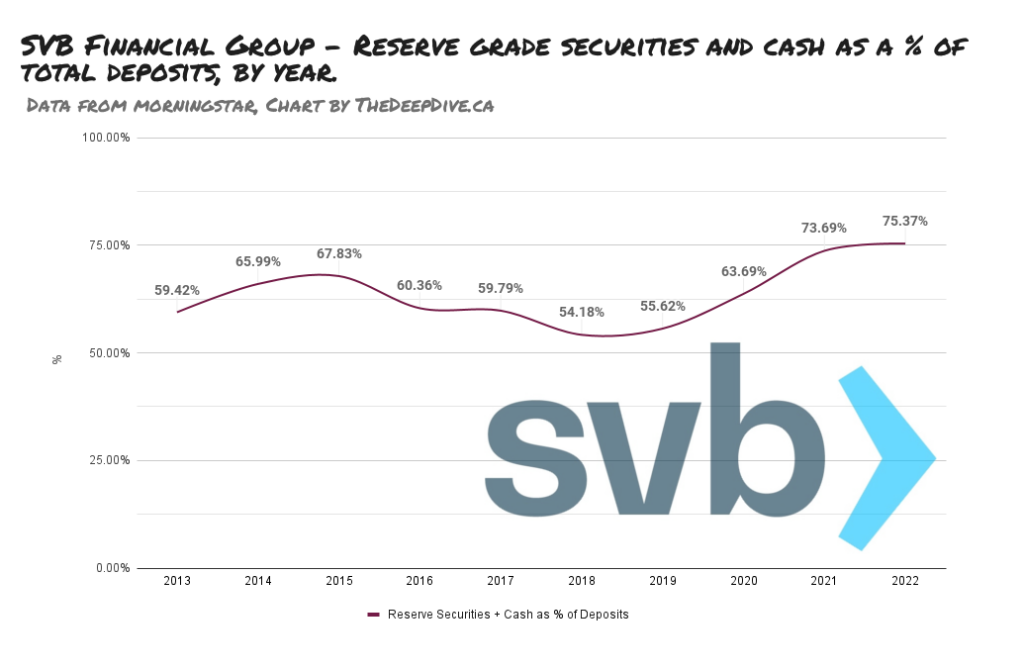

On a historical basis, right before SBC collapsed, its deposits were backed by more reserves than ever before. It also had a total of $32.2 billion in available secured credit at the Federal Reserve Bank, and the Federal Housing Loan Bank of San Francisco, just in case.

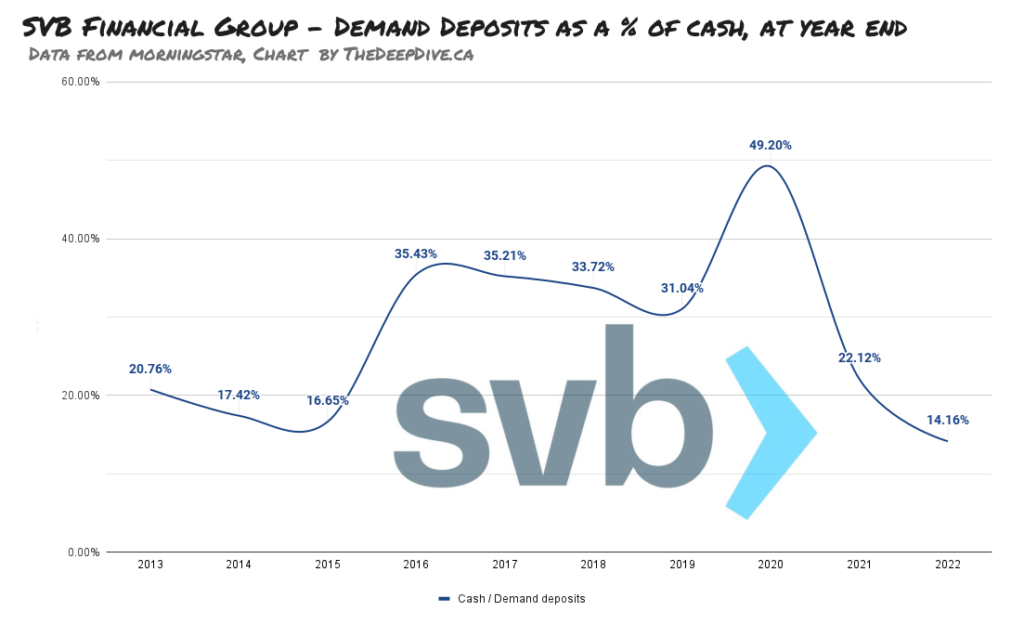

But it’s the demand deposits that SBC needed to be able to cover to stave off its collapse. If more than $13.8 billion worth of those $80.75 billion worth of depositors walked in and start making demands about their money, and those demands weren’t met… it could get ugly.

And by that measure, the pre-collapse SVB’s liquidity was already starting to congeal at the end of 2022. As the bank’s startup and venture-capital fund clients, for whom investment money no longer rains from the sky, all came for their cash all at once… there wasn’t enough to go around.

Press reports have SVB clients calling in to make withdrawals being met with jammed phone lines, and successfully secured outgoing wires being shown at the receiving institutions as “pending.”

We’ll find out when the receiver reports start coming in if SVB exhausted their Federal Reserve and Federal Housing Loan Bank lines of credit before being forced to sell that AFS paper and free up some cash, or if the central banks told them to sell their reserve paper first, and call back if they survived.

This doesn’t happen every day, but it certainly can. No bank has all of its depositors’ money on hand at any given time. Functionally speaking, every bank either finishes the day having met all depositor demands, and standing on its own two feet, or having failed to meet them in a collapse.

The depositors will be able to recover some or all of their money from the FDIC, and for the shareholders, it’s all over but the crying.

It figures to be an entertaining receivership, and any of you sickos who like that sort of thing should get started with The Dive‘s illustrated look at what SVB was when it collapsed: “What Happened at SVB?“

Information for this briefing was found via Edgar, FDIC, and the sources mentioned or linked. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.