- The FDIC insured bank could not meet withdrawal demands, was taken over by regulators Friday.

- $62.5 billion in off-balance-sheet loan commitments may have complicated the cash crunch.

- Insured deposits will be reimbursed by the FDIC. Uninsured depositors will become parties to the coming receivership.

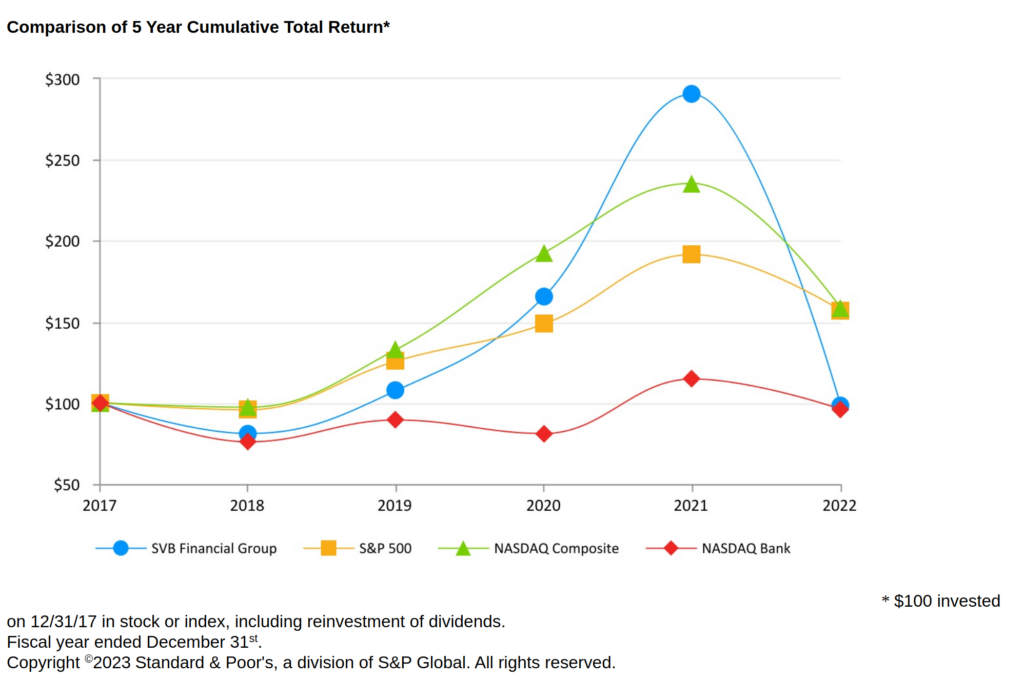

SVB Financial Group (NASDAQ: SIVB), looked to the market like a thriving banking enterprise until this past Wednesday, when it started to show trouble. By Friday, the preferred banker of Silicon Valley venture capital and private equity was in receivership, and we were making charts about it.

Part one, Panic at the Discount Window, charted the particulars of how the banks ran out of money. We’re expanding on it here with some insight into how the enterprise was run, and how it put itself in an unfixable bind.

READ: Panic! At The Discount Window: SVB Collapse Tanks Banks

SVB had a private banking and wealth management division that catered to the “executive leaders of the innovation economy.” The private banking business didn’t have all that much to do with the larger liquidity picture, but it had everything to do with the way this bank generated clients, and those clients are at the middle of the problem.

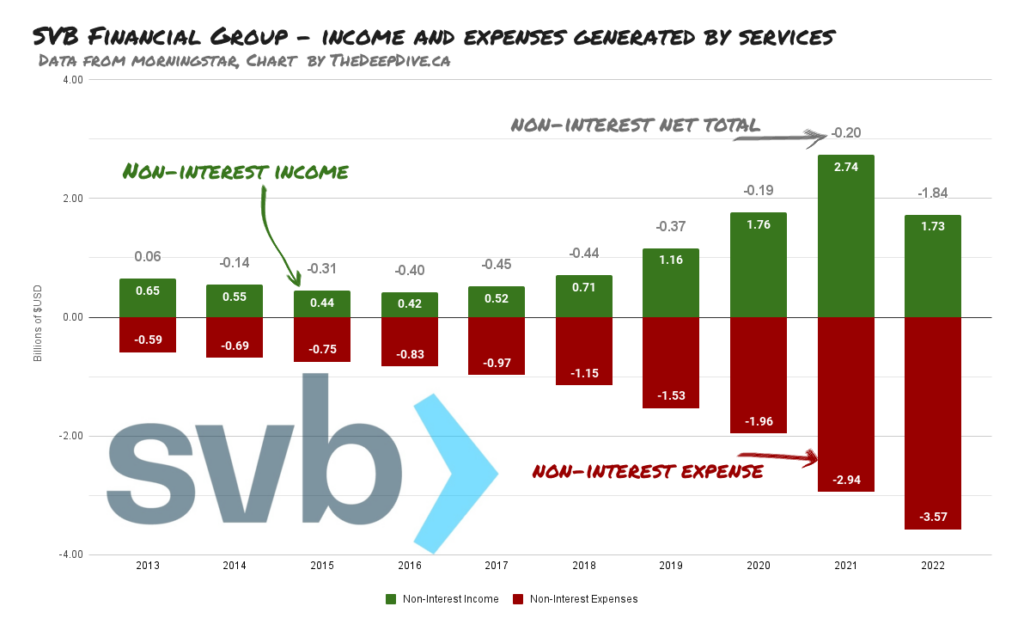

Despite charging fees for most everything, Silicon Valley Bank’s non-interest-generating businesses – everything it does outside of money lending – lost money.

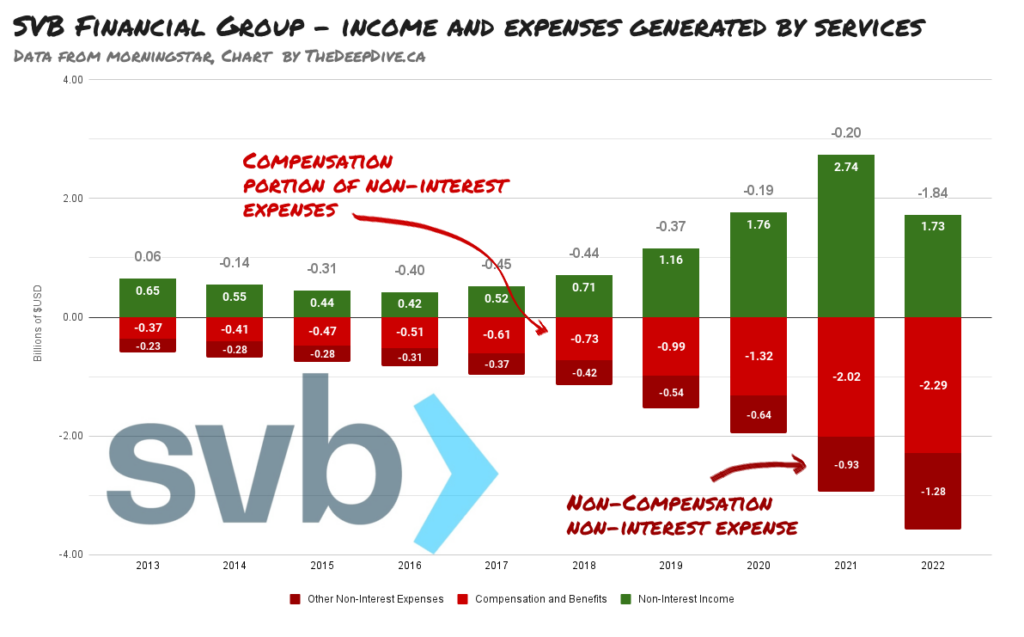

This is uncommon in banking, but not unprecedented. And if we look at the split on those expenses…

… it gives us an idea what they’re up to.

Banking is about relationships

The bold, innovative entrepreneurs of the innovation economy can’t be expected to wait until the magic they’re creating becomes profitable to get paid. They need a bank that understands their unique situation!

Take, for instance, a Palo Alto executive who we invented just now for this example. He works at some company whose disruption of… self driving cars or ride hailing or AI or whatever… it doesn’t matter… This executive’s company’s stock trades publicly on a liquid market… But the value of the considerable stock position that he holds in this bold venture is not presently being appreciated by the market.

And, if he sold that stock position at this price (or any price!) some killjoy would probably pull the Form 4 report and plaster it all over Reddit or worse: a blog, and it would be bad optics.

A banker that understands discretion could either make a loan against that stock position, or set him up with some other capital gunslinger who could make such a loan, save him from having to file Form 4, and get him the cash he needs to buy a new submarine when he needs it! (NOW!)

If the value of the stock he’s pledged goes up, the executive can repay the loan with interest and get it back. If it doesn’t, he defaults, forfeits the stock and files the Form 4, but by then he’s already bought the sub, and there’s no cell service at the bottom of the Monterey Canyon!

To the extent that SVB engages in lending like our invented example on their own books, it doesn’t amount to much. But there is a special bond that forms between bankers who are getting filthy rich running a money-losing division, and executives who are getting filthy rich running a money-losing company. They understand each-other. And banking is about trust.

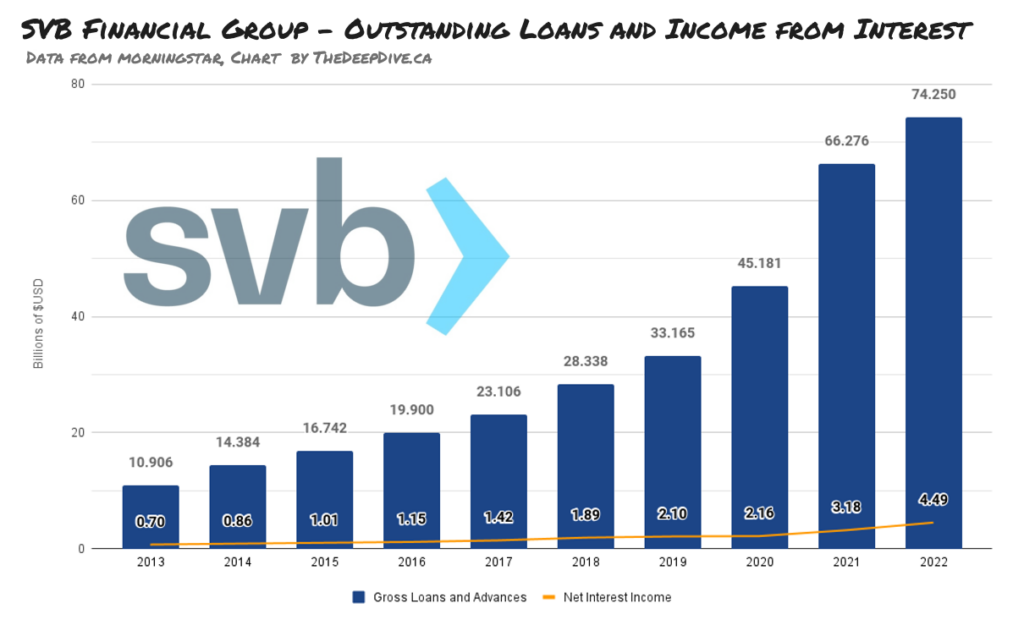

In 2022, SVB earned $4.49 billion in net interest income (income from interest on the loans they make & securities they own, less interest paid on the money they borrow). That isn’t bad at all for money made with other peoples’ money. After figuring in the loss from the services business, the company averaged a bottom line profit of $1.4 billion in each of the past four years. We’ll spare you the chart to keep this moving.

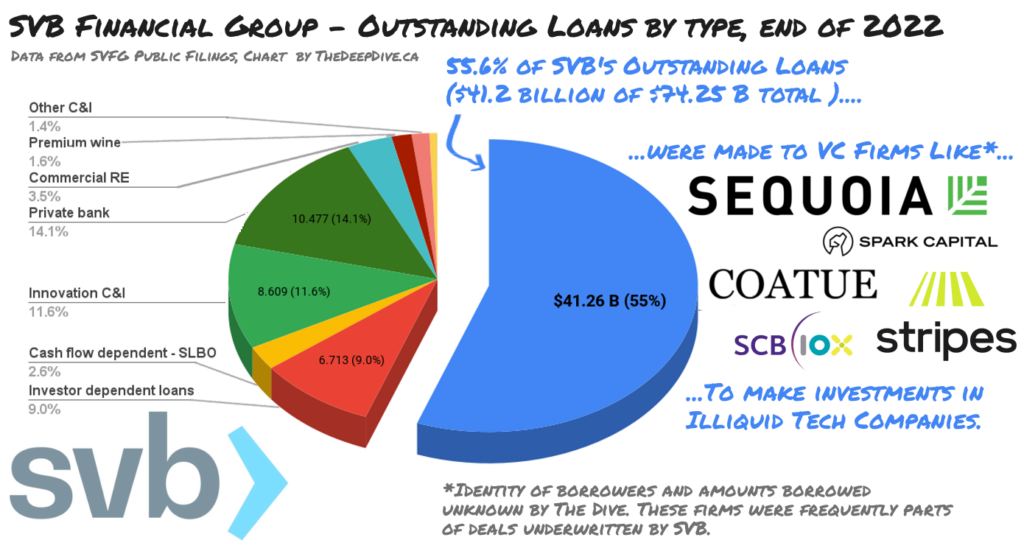

When we break down that loan portfolio, the street’s lack of confidence in 2023 becomes easy to understand.

55% of the SVB loan portfolio consisted of loans to the venture capital and private equity funds that incubate the technology startups whose growth has, for the past 20 years or so, put The Valley awash in a flood of money.

SVB makes direct loans to early-stage, aggressive-growth startups in some cases, but a more typical SVB deal had it lending to a VC fund, which then used the money it borrowed to make an equity investment in a startup on behalf of its investors.

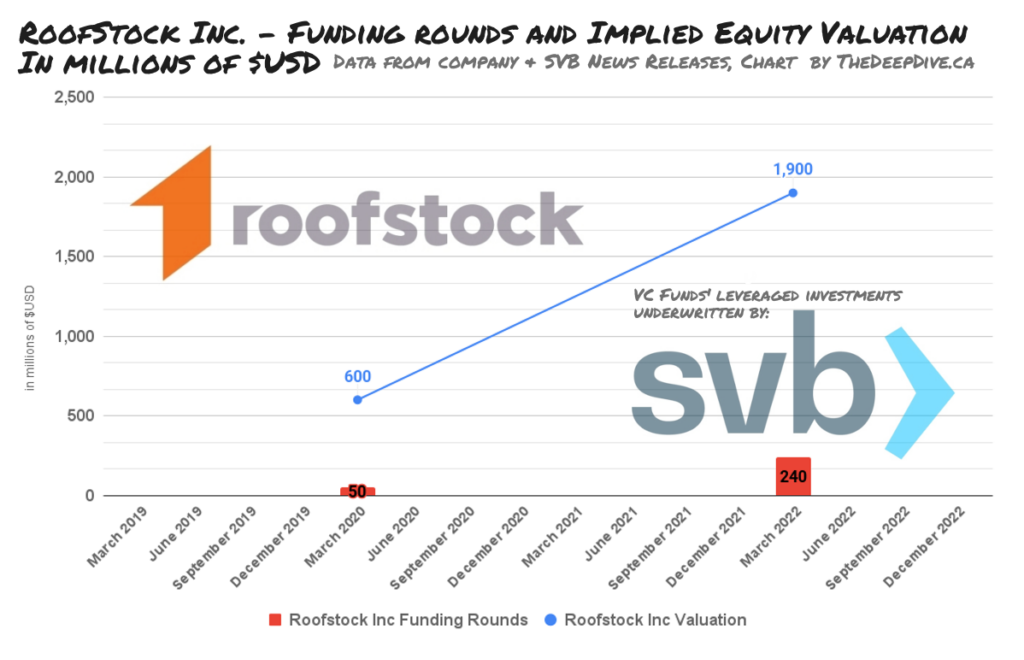

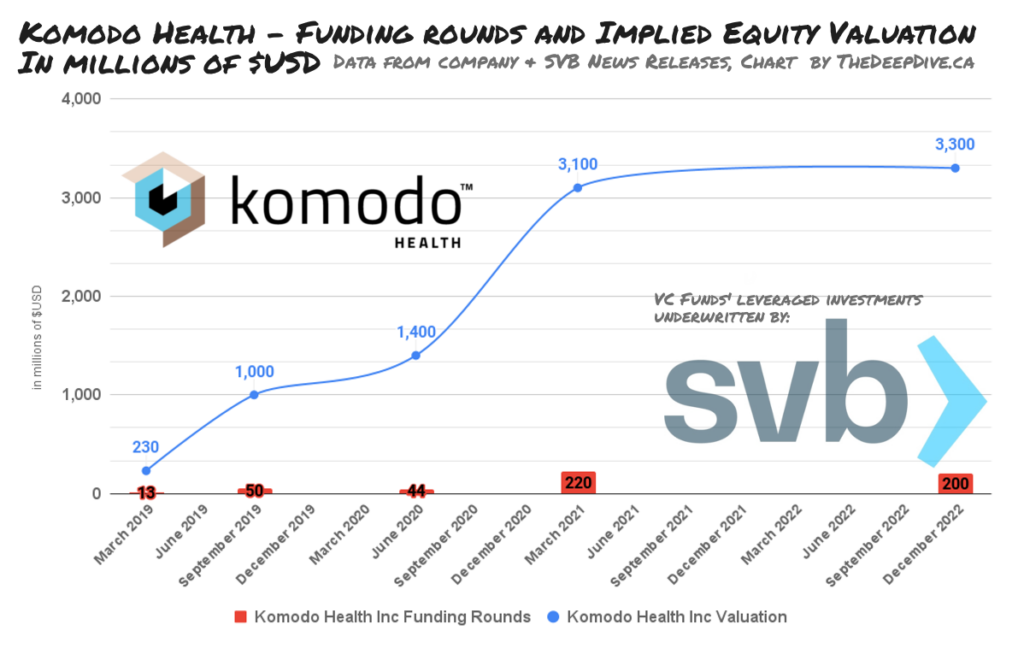

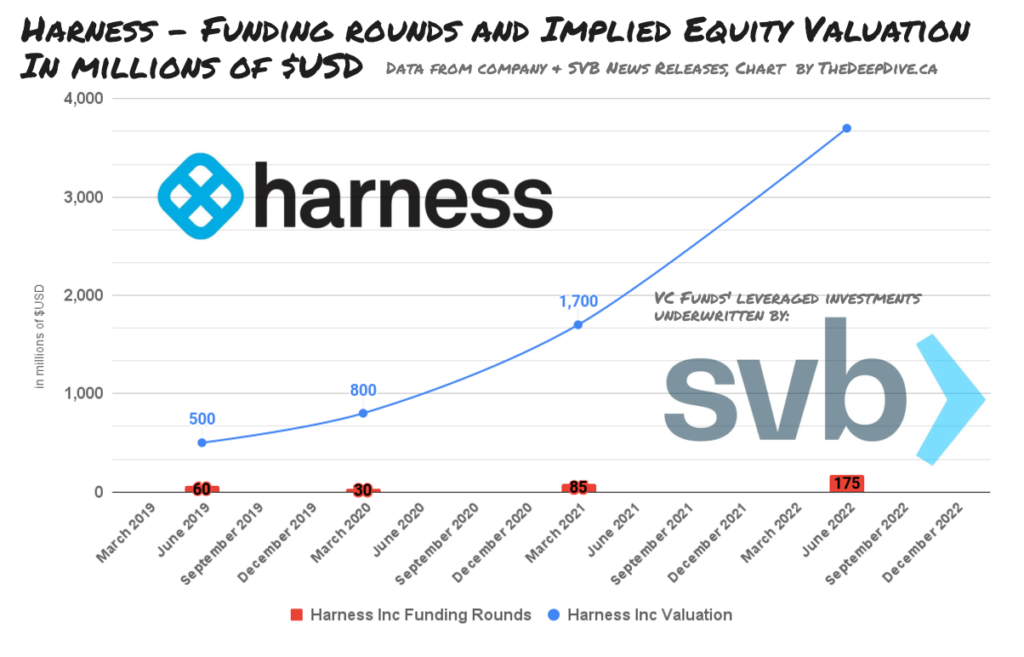

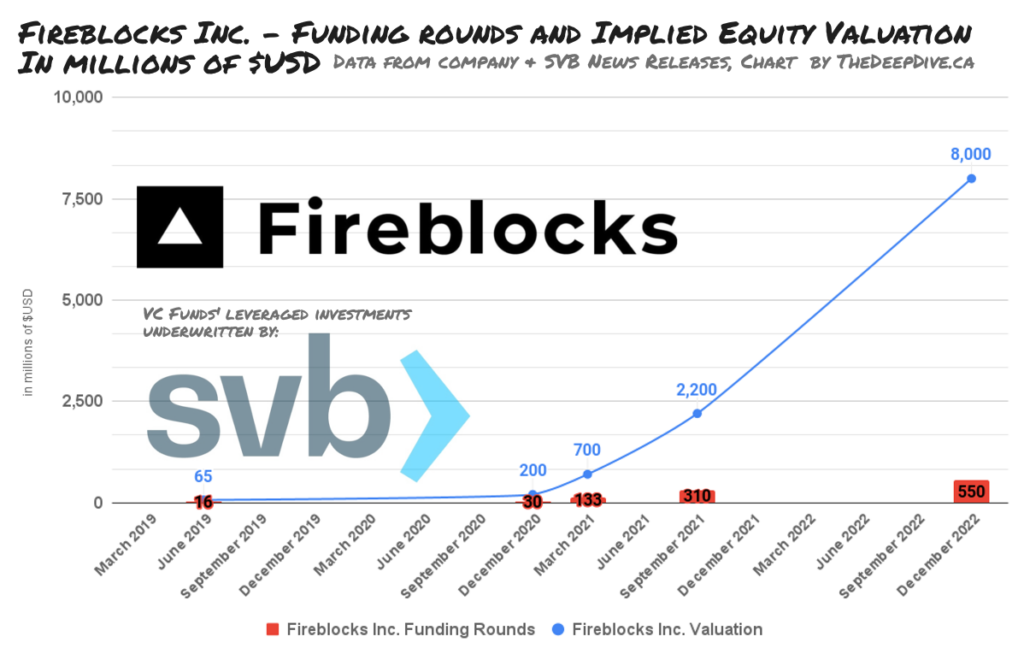

The target companies all make software that makes software, or try to re-shuffle the deck in the rental property market or have something to do with crypto… whatever’s working at the time.

The low rate environment of the past… 20 years or so, had capital moving up the risk curve to chase yield. That made high-growth companies excellent raw materials for the money merchants at venture capital and private equity companies, and their lenders.

A VC fund could park its investors’ capital in a startup’s seed round, watch it grow its top-line revenue at a loss, sell the seed stock to another VC fund that was late to reply to the subscription email for the A-round offering, and get a valuation lift that doubled their money.

The fund’s investors would surely re-invest the proceeds, giving the VC outfit more managed capital, and an opportunity to leverage its next moves with a loan from SVB. They could go after the more expensive C and D rounds in established, growing enterprises, where the real lift was about to happen with an IPO or SPAC listing.

A VC Fund’s most valuable asset is its investors so, often, the funds’ subscription contracts come with capital calls built into them. The VC fund can demand additional capital from its investors, and liquidate the investor’s position in the fund if they can’t come up with it.

That doesn’t sound like such a bad deal to an investor in 2019, who’s trying to invest $40 million in the risk-adjusted 8%-12% return that the VC Fund is generating, but is being told that there’s only space for $20 million. “Of COURSE we’ll cough up another $20 million when you ask for it! We only wish you’d take it now!“

Silicon Valley Bank took assignment of their VC borrowers’ rights to demand additional capital from their investors as collateral for the loans they make to the VCs.

And, sure. It’s obvious NOW that anyone whose most valuable collateral for an investment loan is the right to demand more money from their investment partners is going to become a terrible credit risk when the market tanks… but who could have seen that coming?

Risk goes on, risk comes off…

As interest rates went up, investors lost interest in growth investments that still aren’t profitable enterprises, and don’t expect to be any time soon, because they’re built for growth, not income.

These startups were already going through the cash they’d stashed at SVB quicker than SVB could sell its commercial paper to keep up with the withdrawals, and the next raises are sure to bring lower valuations.

Does anyone believe that, in a post-FTX world, crypto-custodian-co Fireblocks Inc. is worth $8 billion?

To the extent that VC Fund investors would rather be liquidated than double down on yesterday’s garbage, the 55% of SVB’s loan portfolio – $41.2 billion of $74.2 billion – is effectively unsecured debt.

It sounds bad when it’s put that way but, all things considered, it was actually a lot worse.

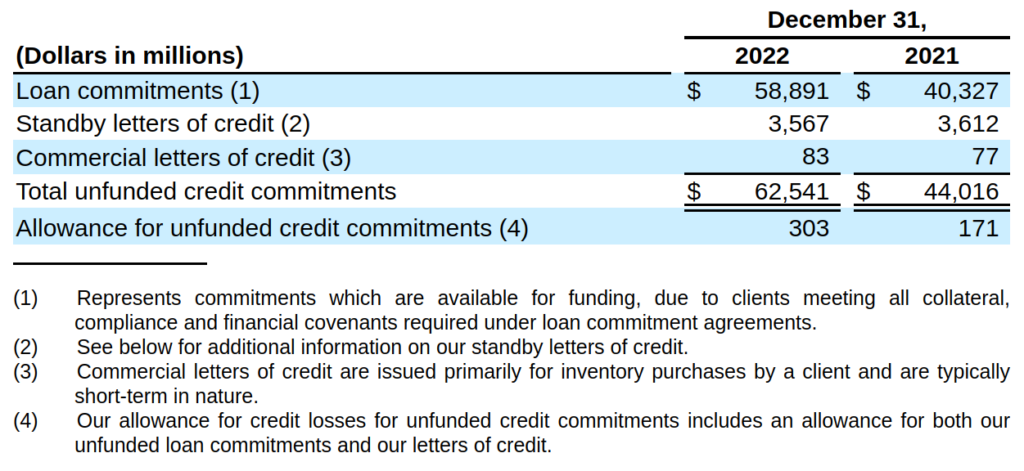

Silicon Valley’s 2022 10-K lists another $62.5 billion in off-balance-sheet loan commitments and standby letters of credit. The figure is “off balance sheet,” because it wasn’t money that had been loaned yet, just money that the bank’s debtors had a right to borrow whenever they like.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one…

The manager of a venture capital fund walks into a Silicon Valley Bank, sits down at the loan desk, and spends 15 minutes or so chatting with the loan officer, whose wife is in his wife’s yoga class, and went to Stanford too!

Eventually, the VC guy asks to borrow $110 million to make the $300 million in investor capital that his fund presently has invested in startups run by various other Stanford graduates go a bit further.

“What have you got for collateral?” asks the loan officer.

“Well, our most valuable asset is our investors, who are contractually obligated to re-invest as much money in our fund as they’ve already invested, whenever we tell them to.”

“Wow!” says the loan officer, “they signed up for that?”

“They sure did. And we’d be happy to pledge those cash calls as collateral for this loan.”

“That sounds like fine security. I can’t believe you sold them on that cash call. Nice work! How much did you want to borrow again? $110 million?”

“Yeah. A hundred and ten… but we might be able to use more so, can we make it $110 million now, but then you have to give us another $290 million whenever we tell you to?”

Then the loan officer laughs at the irony of it all, and signs the commitment anyhow.

This chart from the 2022 SVB 10-K says it all.

The bank hasn’t paid a dividend on its common stock since the 1990s. It positioned itself as the center of gravity of a growth-based economy: mainlining investors’ appetite for risk assets. It out performed everyone while risk assets were all anyone wanted, and investors were buying SPACs without even knowing what they did.

It would loan money to a VC, who would use it to leverage its fund’s investment exposure to various software and health-tech star-ups, who would use the funds to pay staff and executives, who would then deposit it at Silicon Valley Bank, through the Private Banking division, where a wealth manager might suggest that they put some of that cash in a VC Fund, which would then pool it with money borrowed from SVB, buy part of a startup…

With files from Justin Young.

Information for this briefing was found via Edgar, FDIC, and the sources mentioned or linked. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.

2 Responses

The author inventing hypothetical characters shows that this article is actually based on his imagination rather than the truth.

Thanks for reading!