Today our journey takes us through the rise and crash of Carvana, a company that, for a time, seemed to defy the gravity of traditional car sales.

A company founded by a father-son duo, we’ll learn how their impressive start was fueled by the father’s past business, DriveTime Automotive Group, and how the duo came out on top even as the stock came crashing down.

Let’s dive in.

The origins of Carvana

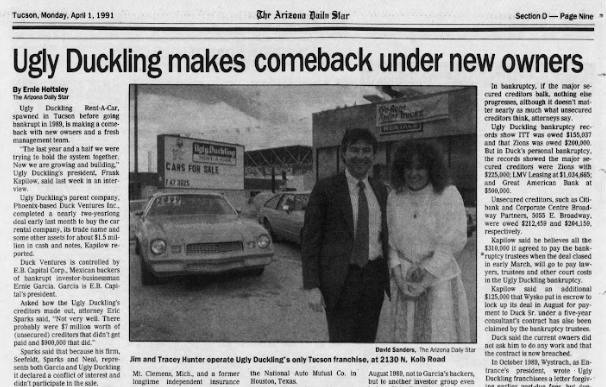

Our story starts with Ugly Duckling, a rental car agency that hit bankruptcy in 1989. Ernest Garcia II tasked himself with picking up the ashes of the company after buying the assets and transforming the company into a dealership model, before picking up financial services assets midway through the ‘90’s. After a brief stint as a public company, in ‘02 Garcia had enough of the public life and bought out shareholders in a go private transaction, while rebranding as DriveTime.

Fast forward to 2012, when Ernest Garcia Jr’s son, Ernest Garcia III, a Stanford University graduate with an engineering degree, gets a gig at his dads company. Fresh out of school, Garcia III, along with Ryan Keeton and Ben Huston, established Carvana as a subsidiary of DriveTime.

An online used car dealer with a twist, Carvana would buy most of their used car inventory from DriveTime, and sell them via “vending machines.” In exchange, Drivetime would purchase the loans that Carvana gave to customers. It was textbook synergy, and perhaps borderline financial engineering, more on that later.

With access to a feast of used car inventory, and a hefty helping of financial support from Daddy DriveTime, Carvana was off to the races, getting big enough that it was eventually spun out in 2014.

The business model

The model for Carvana on the surface is simple. Self-described as the “Amazon for cars,” the company sprinkles in a bit of tech for that extra pizzazz when it comes to making the experience more memorable, which includes the use of its famous car vending machines.

But at its core, Carvana is a used car dealer with the exception of calling their ‘car lots’ vending machines and their website an app.

Customers can look online or go to a physical vending machine to pick out a car. These cars are sourced from auctions, trade-ins, partnered dealerships, individuals – the same as any other used car dealer. Once a car is sold, it’s either delivered to the customer’s doorstep or picked up at one of the 33 futuristic car vending machines across the country. They also offer a seven-day return policy, advertised as a ‘no questions asked’ policy.

Quite simply, the model worked. Well, kind of, if growth is the scorecard and the stock market bubble fueled by near zero rates is your playing field, Carvana was perfect for the game they were playing.

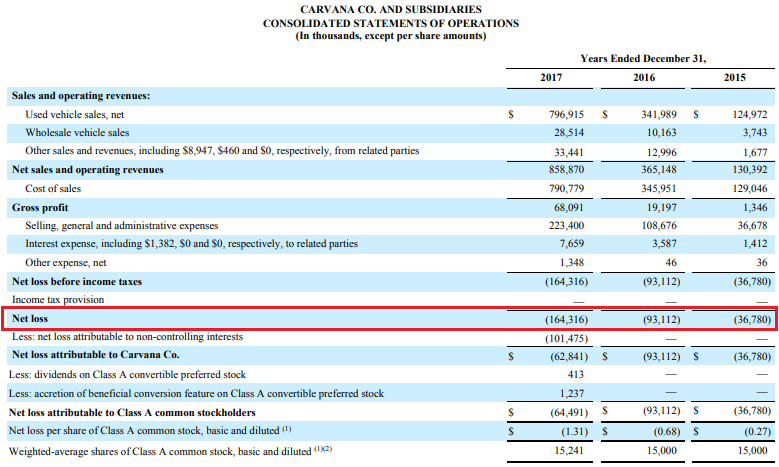

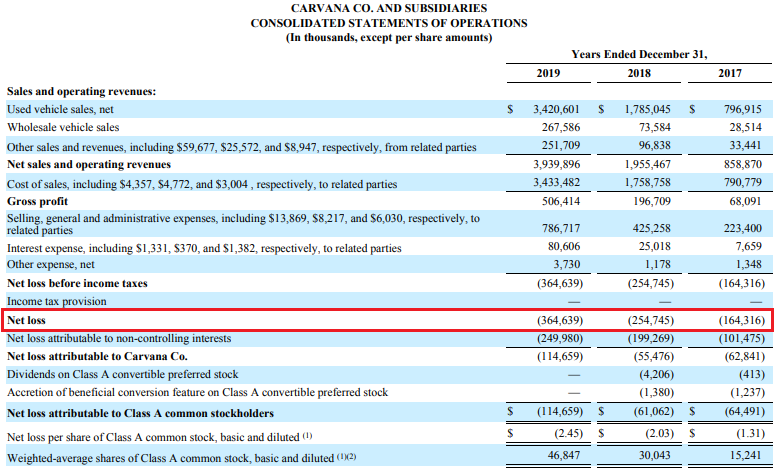

From their humble start in 2012, to going public in 2017, the company saw revenues hit $859 million the year they hit the NYSE, up 135% from the previous year. But there was a problem, that same year, the company still managed to lose $164 million in net income.

The structure

The 2017 IPO saw the company raise $225 million at a $1.5 billion valuation. Not too shabby for a company that started as a family side project.

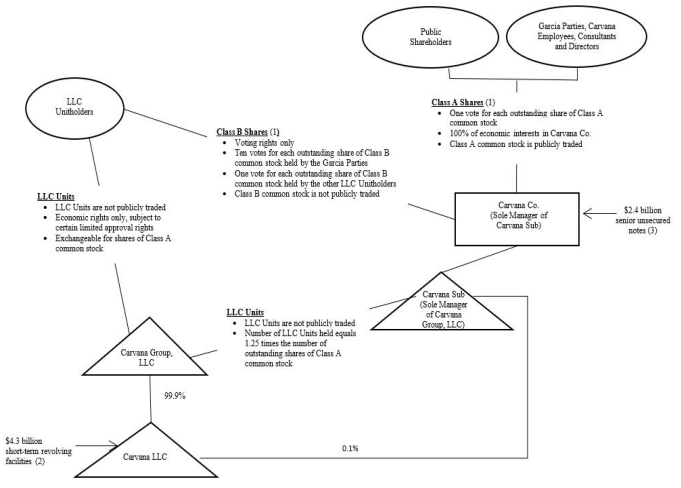

Usually when a company goes public, the trade off is that the original creators give up a stake in the company in exchange for capital – aka money, dollar bills, some green. But in the case of Carvana, the Garcia family retained near complete control over the company. This was thanks to a dual-class share structure where each share held by the Garcia’s was basically like ten shares held by every other shareholder.

Upon going public, the Garcia family held a whopping 97% of the voting interest in Carvana. Meaning if investors were upset, for lets say, Carvana’s stock price cratering due to management incompetence, investors wouldn’t be able to force a change. Well, unless the Garcia family wanted the change, but lets remember Ernest Garcia III was the CEO.

Carvana also set up whats known as a tax receivable agreement during the IPO. It’s a fancy term for a deal where early investors get most of the value of the tax assets. If the company uses these assets to reduce its tax bills, the company agrees to pay beneficiaries of the agreement 85% of that benefit in cash. How much was this tax receivable agreement worth you might ask? $1.1 billion, and most of it is going to the Garcia family.

Are you seeing a pattern?

Carvana, at its core, was just a used car sales company. But with a splash of tech, a dollop of convenience, and a whole lot of Garcia family control.

The early public years

The ‘go public’ however was monumental for Carvana. They now had a new currency to deal in: equity. And they wasted no time doing this.

The same year as their go public, the company bought Carlypso for an undisclosed amount. Months later, they bought Car360 for $22 million.

The purchase of peers proved to be impactful. Revenues soared, reaching nearly $3.9 billion by the end of 2019. Yet, the business still didn’t make much sense from a financial perspective. The company lost a combined $600 million for the years 2018 and 2019.

Despite the finances proving that selling used cars from a vending machine didn’t really make a whole lot of sense, Carvana ended 2019 with a valuation of nearly $5 billion, the beneficiaries of a bull market focused on anything with a hint of tech.

And so, Carvana raced through its early years, making daring acquisitions, and posting impressive sales growth, all while expecting losses funded by investors and the Garcia family continuing to see their net worth get even bigger.

The pandemic tailwinds

And then 2020 hit, and with it, a pandemic that was sure to kill any business in its path. But when your business model revolves around minimal physical contact and no sleazy car salesmen, a global pandemic is the equivalent of striking gold.

And gold it was. Carvana saw revenues grow to $5.6 billion by the end of 2020 and more than double in 2021, to $12.8 billion. Investors took note of this massive growth and started to aggressively buy Carvana’s stock.

And guess who was there to capitalize on this massive windfall?

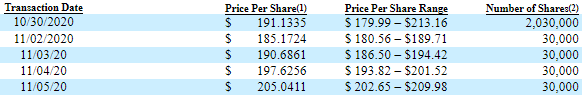

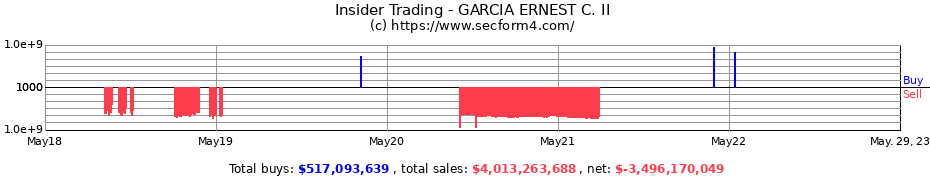

You guessed it, the father and son duo. Ernie Garcia II would start to sell shares daily for months, selling 30,000 shares a day, under an automated share-sale program known as a 10b5-1 plan. (proof of sales starts here in november and goes forward afterwards)

But the party didn’t stop there. As the stock price soared above $350 in the summer of 2021, Juniors sell-off increased to 60,000 shares on most days. By the time the dust had settled, Junior had managed to offload more than $3.5 billion over ten months as investors continued to hit the buy button.

On the business side of things however, it wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows. While they were busy introducing touchless delivery and pick-up, and watching their stock prices soar, they had a few bumps in the road.

They were banned from selling cars in the Raleigh area of North Carolina until January 2022, after the North Carolina Division for Motor Vehicles sued, claiming that they failed to deliver titles to the DMV, all while selling vehicles without a state inspection.

But the even bigger problem. Despite revenue soaring, the company still lost money. Losses in 2021 grew to negative $287 million.

So, while the world was in lockdown, Carvana was busy transforming the used car market – and the Garcia family was turning that into a personal cash cow despite the company still losing money.

Carvana’s decline

So, we’ve covered the meteoric rise of Carvana, but as they say, what goes up must come down. And boy, did Carvana come down. By the end of 2021, their market cap was sitting pretty at $20 billion. Fast forward to today, and it’s a sobering $2.1 billion.

Now, you might be wondering what brought about this precipitous fall from grace. Well, let me tell you, it was a combination of factors.

First off, Carvana co-founder and CEO Ernie Garcia III said on the company’s fourth quarter earnings call that 2023 would be “a difficult one” for Carvana, citing a normalization of the used vehicle market from its inflated levels and increasing interest rates. Among other factors he described the end of the third quarter as the “most unaffordable point ever” for customers who finance a vehicle purchase.

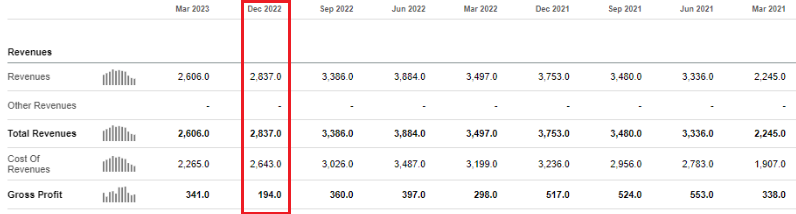

And this showed in the financials. In Q4 of 2022, Carvana saw revenues drop 16% in a single quarter, while at the same time posting a loss of $1.4 billion, a number almost equal to the cumulative loss for the company since going public.

Then there were the legal issues. Carvana was banned from doing business in Illinois, not once, but twice, over registration and title issues. They were handing out temporary registrations from other states like candy at a parade, which caused some customers to get ticketed.

Not exactly a great look for such a large brand.

But the cherry on top of this disaster sundae was their $2.2 billion cash acquisition of Adesa’s US auction business. Now, you might think that adding 56 physical sites would be a good move, but Carvana’s decision to borrow $3.3 billion to fund the purchase only ballooned their interest expense. Their business model, which once seemed innovative and pandemic-proof, started to crumble under the weight of mounting debt and legal issues.

So, while Carvana’s rise was impressive, their fall was even more dramatic. But hey, it’s not all bad. At least they now have 56 physical sites to hold all those unsold cars.

In conclusion

Let’s wrap it up.

As we reach the end of our high-octane journey through the rise and fall of Carvana, we’re left with some important lessons in the rearview mirror.

For a while, Carvana seemed to be the ultimate disruptor in the used car market, blazing a trail with its innovative business model, or at least that is what the Garcia family wanted you to think as they sold multiple billions of dollars of shares into the open market.

Yet, as history has often shown us, even the most promising ventures can hit a bump in the road, especially when they’re steered by unchecked ambition, family control, and a lack of regulatory compliance.

Alright everyone, thanks for joining us on this ride, and until next time, keep your eyes on the road ahead and always do your due diligence when buying a high flying tech startup – especially from a used car salesman.

Information for this briefing was found via Edgar, Seeking Alpha and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.