Congratulations! If you’ve been following along (see Part 1 and Part 2), you’ve now made it to your target company’s document page, which hosts the documents that you can use to conduct your analysis.

What could I possibly have left to explain? Well, as it turns out, there are several oddities to a company’s document page that you’ll probably want to know about.

RTOs

When you arrive on the document page of a company you are researching, one of the first things that might jump out at you as you scroll down is just how many documents there are. Perhaps, too many?

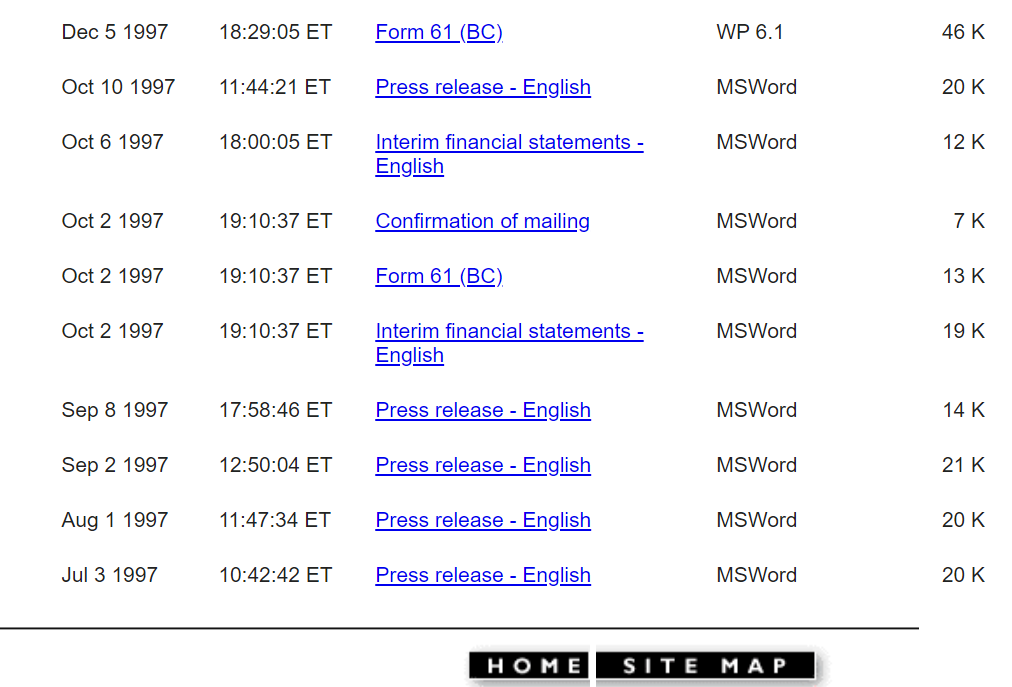

For example, on cannabis retailer MedMen Enterprises Inc.’s (“MedMen”) document page you can find files going as far back as 1997 – decades before MedMen ever went public or even commenced operations. (Hey, some of the documents are even in WordPerfect!)

While you might be tempted to believe this is the result of a gross mislabeling or misfiling, the actual reason for this has to do with the way many companies go public in Canada. It is very common for companies to go public through a reverse takeover (“RTO”) of an existing company that is already public, as opposed to an initial public offering (“IPO”).

When a company goes public via an RTO, all the old filings from the ‘previous’ public company are left up on SEDAR, resulting in ‘new’ companies having files that can stretch back for decades. This explains why many cannabis companies, whose operations were only legalized over the past few years, have public documents stretching back decades. This RTO process can happen multiple times over the life of a public company, so you might even find that a public company you are researching has been engaged in a variety of different businesses over the years.

Year Ends and Filing Dates

If you are trying to compare the results of public companies, you might be frustrated to find that one of the companies you are trying to compare has not yet uploaded their financial documents to SEDAR – even though everyone else in your comparison group has. Before you decide to send an angry letter/tweet to their investor relations department accusing them of being a delinquent filer, there are two important items you should check first.

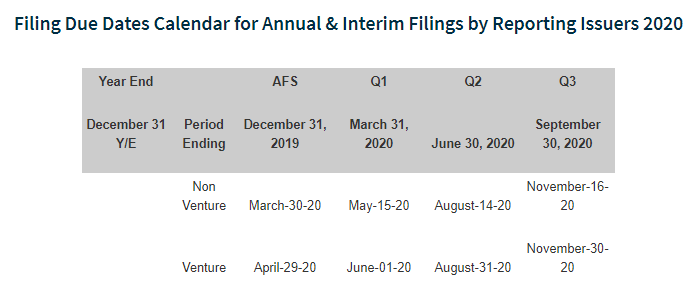

First, while we generally tend to think of December 31 as the end of the year, many public companies have fiscal year ends that end on a different month. For example, cannabis producers Aphria Inc. (“Aphria”) and Hexo Corp. (“Hexo”) have fiscal year ends that end on May 31 and July 31 respectively. This means that the timing and release of their quarterly and annual results will differ considerably from a company whose year end is set for December 31, such as cannabis producer VIVO Cannabis Inc. (“VIVO”). To confirm when a company is required to file their financials, you can check the year-end date on their SEDAR profile page and then cross-reference the deadline schedule on sites that list them, such as the Ontario Securities Commission website.

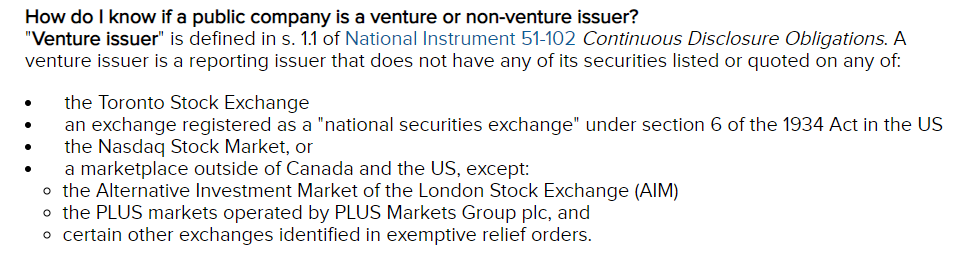

The second consideration is whether the company you are researching is a ‘venture’ or ‘non-venture’ issuer. In a nutshell, companies that are venture issuers are given more time to file their quarterly and annual financial statements and generally have more lax disclosure requirements than non-venture issuers. For example, a public non-venture issuer whose most recent year-end was December 31, 2019 would have had until March 30, 2020 to file their annual financials while a venture issuer would have until April 29, 2020. While you might be tempted to think that the difference between venture and non-venture issuers boils down to size or total assets, there is a specific technical definition that addresses where a company’s securities are listed.

If you spend enough time on SEDAR, you will soon notice a variety of behaviours from companies when it comes to filing deadlines. Some companies will diligently put out an early press release informing you of the exact time they plan on uploading their documents. Some, however, will just quietly submit their financials 15 minutes before deadline like a kid sliding their homework under the door.

Special Filings

As you familiarize yourself with SEDAR, you will pick up on the usual rhythm of quarterly financial statements, management discussion & analysis reports, management information circulars, and the occasional, (or very VERY frequent) press release. You’ll also likely notice that some companies seem to upload uniquely detailed documents, while other companies may not upload them at all. Examples of these documents include business acquisition reports, credit agreements, and material contracts.

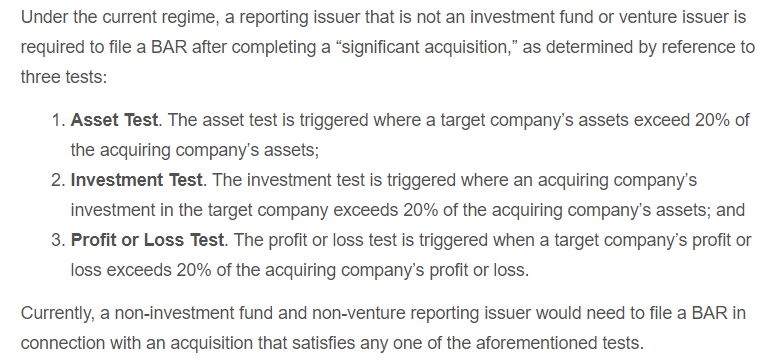

One such example of these unique filings is a business acquisition report, which provides granular details about a specific acquisition a company has made. You’ll find that some companies may file these for certain acquisitions, but not for others, while other companies who have made extensive acquisitions don’t file them at all. The reason for this is that there are specific thresholds that must be met before a company has to make a special filing, like a business acquisition report, making them something of a sporadic occurrence.

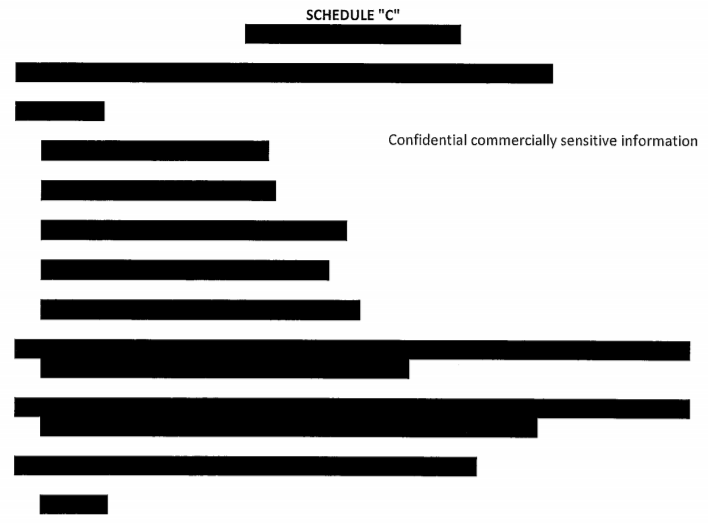

Even when companies are required to file these documents, you might find yourself frustrated at the level of detail they provide. It is not uncommon for companies to redact substantial sections of these documents, such as the debt covenants in a credit agreement or the key economic terms of a material contract the company has executed. For example, below is an excerpt of the economic terms from Beleave Inc.’s note purchase agreement with Auxly Cannabis Group Inc.

As you can see, these aren’t always swimming with detail.

A Few Thoughts

Despite its somewhat archaic design, the ability to navigate SEDAR and access the key documents a public company is required to file can be an exceptionally empowering tool. This skill is not just beneficial to the investors and analysts who own and trade public securities; but can also be tremendously valuable to private companies who want to better understand their customers or competition. For example, if you owned a construction company and were offered a contract to work with a public company, you might find it beneficial to know how much cash they have, what their sales are like, and whether or not they are struggling to pay their bills.

If you are new to public company research, think of this guide as a first step on a long path that will be frustrating at times – but can begin to pay considerable dividends over time.

Best of luck.

(For a list of where you can find key information about a company, such as how much cash they have or what are they paying their executive team, move forward to Part 4, out tomorrow.)

Information for this commentary was found via Sedar. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization or any organization mentioned. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.

New SEDAR Is Somehow Worse Than Old SEDAR

“UI”, and “UX” weren’t considerations in the pre-iMac world where the crude instrument that was...