Feature image adapted from original art by Victor Bonaccius.

It’s difficult to write about UBER without using modern business cliches. It’s a platform business that set out to disrupt the taxi industry, and has since pivoted to takeout. Like the overbuilt startups that preceded it, Uber’s operations lose money. Quite a bit of money.

Uber printed a -$3 billion operational loss in Q2 2021, and has been pretty steady about that for its life as a public filer. Conventionally, ventures lose money as they scale up, then cut costs either across the board or in certain verticals to achieve profitability.

But “scaling,” in the platform software business happens out of the gate. The nature of doing dispatch and order matching through an app is that it can handle as many riders, drivers, eaters, and restaurants as any given urban area can throw at it, without having to hire more staff. Uber isn’t burning billions every quarter to scale its operations, it’s doing it to expand them.

How it works

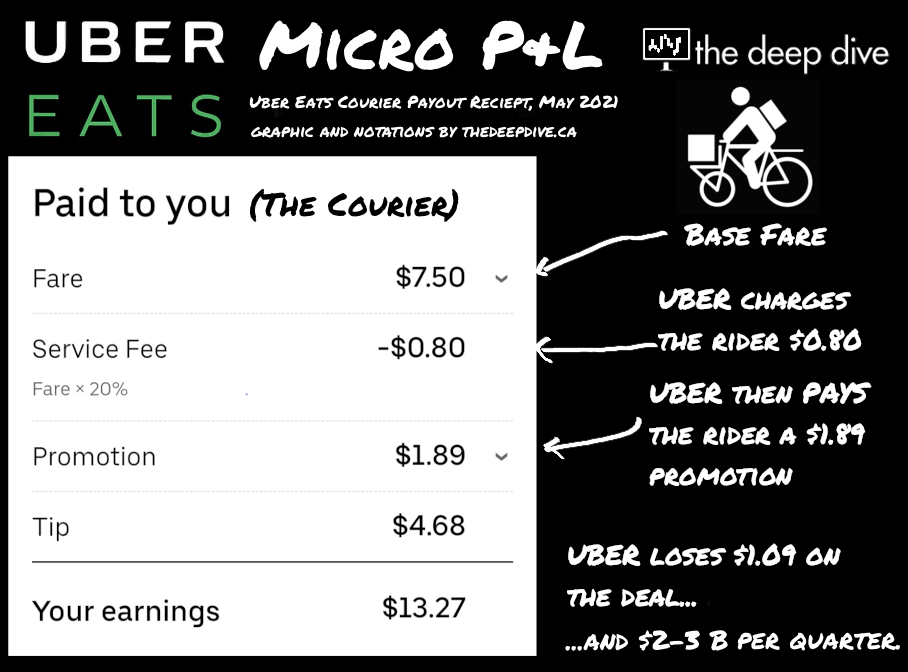

On paper, Uber’s customers aren’t the people who use the app to book rides or have takeout delivered. Those are users. The “customers” are the independent contractors who make the trips with people, food or groceries. When a trip is complete, the users pay the drivers and the restaurants, and Uber collects a fee for putting them together and handling the transaction.

The reason nobody ever did this type of thing before Uber did is that the price a consumer is willing to pay for a ride or a delivery is often a lot less than the driver’s time is worth. Uber makes up the difference with a promotion in excess of the fee they charge, and by encouraging the users to give the drivers gratuities.

Accordingly, an unknown amount of Uber’s sales and marketing budget should really be a cost-of-sales line.

Uber’s selling and marketing expeneses track both total revenue and total trips so closely because Uber’s “promotional” discounts to customers and bumps for the drivers are what make the trips worth the driver’s time, or put them at a price point that a consumer is willing to accept.

Running at a loss on both the micro and macro scales doesn’t seem to bother them, so long as the trips happen. This stage of the platform model is all about making those trips happen.

Examplezon

The contemporary modern example of a platform business is Amazon. AMZN ran at a net loss through its early years, but has steadily grown its profits on an annual basis since 2015. Amazon includes both a retail sales platform and a web hosting platform, and the leverage in both verticals comes from Amazon’s total domination.

Since Amazon represents a majority of retail sales for most consumer goods categories, it can dictate which bicycle pump or car cover or cell phone case is exposed to the most consumers, and charge the manufacturers or distributors a premium for better exposure to retail buyers. The retail landscape of 2021 is one that Amazon controls, because they invented it.

Allllllllll the money!

The prospect of Uber establishing that sort of dominance is likely central to its continuing appeal as an investment, despite being a consistent cash fire.

The flattening revenue curve doesn’t appear to concern Uber, and neither does a flattening trips recovery curve, because the metric that really matters is travelling in the right direction, and it’s enormous.

Gross bookings represents the total value of all of the transactions Uber handles, including the promotions that it floats to make the transactions work. Uber handled a record $21 billion in gross bookings in Q2 of 2021, and growing. As those taxi trips become parts of users’ daily and weekly routines, and the takeout orders come to represent a larger and larger portion of restaurants’ volume, Uber has effective control of a larger and larger logistics economy.

The bookings growth has hardly been organic. Uber has grown its delivery vertical through the acquisition of smaller delivery apps like Postmates and Didi, and is expanding into grocery delivery through the recent acquisition of cornershop. To be the only platform that handles both those verticals, Uber will have to keep going. Lyft and DoorDash are necessary acquisition targets for an Uber monopoly.

On a long enough timeline, investors will cease to be interested in subsidizing this endless, money-losing expansion, but they’re plenty interested right now. Uber floated a $1.5 billion bond offering August 9th to finance its acquisition of Transplace, and a further expansion into its freight vertical.

Eventually, when Uber controls a large enough chunk of its respective verticals, it has various options available to make the business make money. An Uber of the future that has consolidated all relevant competition could charge higher fares to its users, and or reduce the take for drivers. The alarming number of people who subsist on takeout are a customer segment worth fighting over, and the McDonalds’ and Chipoles of the world have the war chests to fight over it.

Uber’s $80 billion market cap looks bloated in the context of its consistent operational loss, and especially in the context of a gross profit that is augmented by its promotional budget. But when one considers the fact that the company has de facto control over a logistics economy that did $73 billion worth of commerce in the trailing 12 moths, it’s practically the ground floor of an emerging infrastructure layer.

Information for this briefing was found via Edgar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.