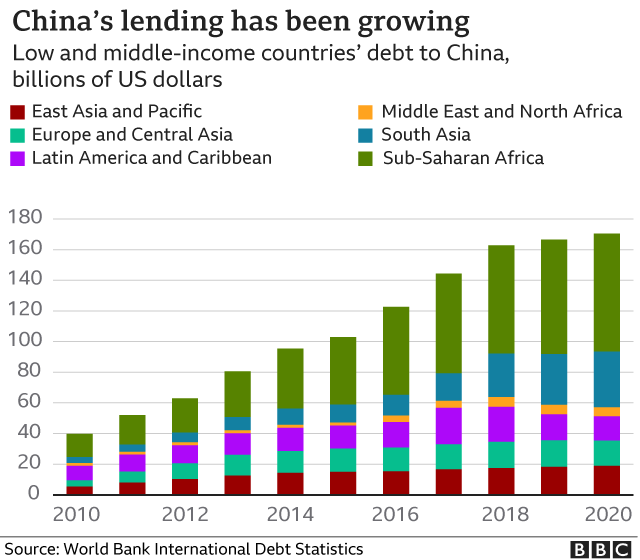

A dozen poor countries are facing economic instability and even collapse as a result of hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign loans, the most of which are from China, the world’s largest and most unforgiving government lender.

According to an Associated Press investigation of a dozen of the most indebted countries to China, including Pakistan, Kenya, Zambia, Laos, and Mongolia, repaying that debt is eating an increasing portion of the tax money needed to keep schools open, provide energy, and pay for food and fuel. And it’s depleting the foreign currency reserves that these countries rely on to pay interest on their loans, leaving some with only months until the money runs out.

Countries in the AP’s analysis received up to 50% of their foreign loans from China, and most spent more than a third of their government revenue on debt repayment. Zambia and Sri Lanka have already gone into default, unable to make even interest payments on loans used to build ports, mining, and power facilities.

Millions of textile workers in Pakistan have been laid off because the country has too much foreign debt and cannot afford to keep the lights on and the machines operating.

In Kenya, the government has withheld payments from thousands of civil servants in order to save money to pay off foreign loans. Last month, the president’s main economic adviser tweeted, “Salaries or default? Take your pick.”

Since Sri Lanka’s default a year ago, 500,000 industrial jobs have been lost, inflation has reached 50%, and more than half of the country’s population has plunged into poverty in several areas.

Behind the scenes, China’s unwillingness to forgive debt and its extraordinary secrecy about how much money it has loaned and on what circumstances has prevented other large lenders from stepping in to assist. On top of that, it was recently discovered that borrowers were obliged to deposit funds in concealed escrow accounts, effectively pushing China to the front of the line of creditors to be paid.

Experts believe that unless China softens its position on lending to poor countries, there will be another wave of defaults and political upheavals.

China's grand plan for winning international influence:

— Noah Smith 🐇🇺🇦 (@Noahpinion) May 20, 2023

1. Launch money at other countries out of a T-shirt cannon

2. Hahaha you thought that was a gift? It was a LOAN, now pay us back suckershttps://t.co/gLegRPlZEF

Debt trap diplomacy

One of the more successful strategies by Beijing in gaining global influence is offering economic and development benefits to other countries under the guise of a loan. Called “debt trap diplomacy,” many nations are forced into allegiance or giving preference to mainland China in the geopolitical landscape after being unable to repay borrowed investments from Beijing to finance their respective countries’ development projects.

Forbes reported that 97 countries throughout the world are in debt to China, using World Bank data. Countries that owe China a lot of money are largely in Africa, although they can also be found in Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Pakistan owes Beijing the most money: $77.3 billion, Angola $36.3 billion, Ethiopia $7.9 billion, Kenya $7.4 billion, and Sri Lanka $6.8 billion.

More recently, China established diplomatic ties with Honduras after the Central American country severed ties with Taiwan. Honduran Foreign Minister Eduardo Enrique Reina signed the agreement on diplomatic recognition in Beijing, releasing a statement saying Honduras acknowledges the People’s Republic of China as the only legal government representing all of China and that Taiwan is a “inseparable part of Chinese territory.”

In a news conference, Taiwan Foreign Minister Joseph Wu stated that he received a letter from Reina requesting $350 million for a hydroelectric dam and $90 million for a hospital, which had been doubled from an initial $45 million without reason. Reina also requested that Taiwan assume $2 billion of Honduras’ national debt.

According to Wu, the Honduran government demanded direct financial support, despite Taiwan’s regular practice of being involved in the construction, purchasing of materials, and follow-up operations of infrastructure projects in allied countries.

Such activities, according to the foreign ministry, are unacceptable in Taiwan, as “giving money directly [to a government] is like offering bribes.”

Wu accused Beijing of making “ostentatious commitments” on a regular basis in order to entice Taiwan’s diplomatic partners to transfer diplomatic recognition. Yet, once China has achieved its diplomatic goals, it frequently fails to keep its promises, leaving some beneficiary countries in debt.

He stated that, in contrast to China, Taiwan would only approve projects that serve the people and national interests of its allies, of which there are currently just 13 left.

Zambia: landlocked country trapped in debt

Zambia, a landlocked country of 20 million people in southern Africa, has borrowed billions of dollars from Chinese state-owned banks over the last two decades to build dams, trains, and highways.

The loans strengthened Zambia’s economy, but they also increased foreign interest payments to the point where the government had nothing left over, forcing it to decrease spending on healthcare, social services, and seed and fertilizer subsidies to farmers.

In the past, huge government lenders like the United States, Japan, and France would work out accords to forgive some debt, with each lender fully revealing what they were due and on what terms.

China, on the other hand, has a different strategy. First, it first refused to participate in multinational discussions, instead negotiating directly with Zambia and insisting on confidentiality that forbade the country from disclosing the conditions of the loans or whether China had discovered a method of muscling to the head of the repayment line.

Add to this dilemma that some non-Chinese lenders refused desperate pleas from Zambia to suspend interest payments, depleting the country’s reserves further. By November 2020, Zambia had ceased paying the interest and defaulted, thereby locking it out of future borrowing and triggering a vicious circle of budget cuts and worsening poverty.

Zambia’s inflation has subsequently risen to 50%, unemployment has reached a 17-year high, and the country’s currency, the kwacha, has lost 30% of its value in just seven months. According to the United Nations, the number of Zambians who do not have enough food has nearly tripled this year, reaching 3.5 million.

A few months after Zambia defaulted, analysts discovered that it owed $6.6 billion to Chinese state-owned banks, which was more than double what many thought at the time and accounted for around one-third of the country’s entire debt.

China’s refusal to accept large losses on hundreds of billions of dollars owed, as advocated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB), has placed many countries on a treadmill of paying back interest, stifling economic growth that might help them pay off the debt.

Foreign cash reserves have fallen in ten of the dozen countries studied by AP, falling by an average of 25% in a year. In Pakistan and the Republic of Congo, they have dropped by more than half.

Without a bailout, numerous countries have only a few months of foreign currency to pay for food, fuel, and other necessities. Mongolia has eight months remaining. Pakistan and Ethiopia each have roughly two.

Joint action, fair burden

In a statement to the Associated Press, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuted the notion that China is an unforgiving lender and reiterated past statements blaming the Federal Reserve. It stated that if it is to comply with IMF and WB demands to cancel a portion of its loans, then so should those multilateral lenders, whom it regards as US proxies.

“We call on these institutions to actively participate in relevant actions in accordance with the principle of ‘joint action, fair burden’ and make greater contributions to help developing countries tide over the difficulties,” the ministry statement said.

China claims it provided help through prolonged loan maturities and emergency loans, as well as being the largest contributor to a scheme that temporarily suspended interest payments during the coronavirus outbreak. It also claims to have forgiven 23 no-interest loans to African countries, but AidData, a research lab at William & Mary that has uncovered thousands of secret Chinese loans, claims that these loans are primarily from two decades ago and represent less than 5% of the total amount lent.

The IMF and WB argue that paying losses on their loans would shatter the customary playbook for dealing with sovereign crises, which gives them preferential treatment because, unlike Chinese banks, they already lend at low interest rates to assist fragile countries recover. However, the Chinese foreign ministry pointed out that the two multilateral lenders have made an exception in the past, forgiving loans to many nations in the mid-1990s to save them from bankruptcy.

China has also resisted the notion, promoted by the Trump administration, that it has engaged in “debt trap diplomacy,” in which it has plagued countries with loans they cannot afford in order to seize ports, mines, and other key assets.

Experts who have thoroughly researched the topic have sided with Beijing on this point. Chinese credit has come from dozens of mainland institutions and has been far too random and sloppy to be coordinated from the top. They argue that Chinese banks are not accepting losses because the timing is poor, since they face significant losses as a result of imprudent real estate lending in their own nation and a significantly weakening economy.

However, analysts are also eager to point out that a less sinister Chinese role is no less frightening.

Currency swap loans

Meanwhile, Beijing has engaged in a new type of secret lending, adding to the confusion and distrust. AidData discovered that China’s central bank has been effectively lending tens of billions of dollars via what appear to be typical foreign currency exchanges.

Foreign currency exchanges, known as swaps, allow governments to essentially borrow more frequently used currencies, such as the US dollar, to fill temporary gaps in foreign reserves. They are designed for liquidity, not construction, and have a limited lifespan of a few months.

However, China’s swaps are similar to loans in that they continue for years and have higher-than-normal interest rates. Furthermore, they do not appear on the books as loans that would add to a country’s total debt.

The swaps can help prevent default by replenishing currency reserves, but they pile more loans on top of old ones and can exacerbate a collapse, similar to what happened in the run-up to the 2009 financial crisis when U.S. banks continued to offer ever-larger mortgages to homeowners who couldn’t afford the first one.

For years, Mongolia has taken out $1.8 billion in such swaps yearly, an amount equal to 14% of its annual economic output. Pakistan has received roughly $3.6 billion annually in this manner while Laos has received $300 million.

Some countries straining to repay China are now locked in a financial limbo: China will not accept losses, and the IMF will not grant low-interest loans if the money would only be used to pay interest on Chinese debt.

That’s when the debt trap becomes a sinkhole.

Information for this briefing was found via Fortune and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.