News broke this past Monday that Canadian department store chain The Hudson’s Bay Company is being accused by Canadian landlords Oxford Properties and Cominar (TSX: CUF.UN) of skipping out on its rent at two of its Canadian locations. The Toronto Star reports that the iconic company gave its landlords the shaft, along with a letter informing them that they ought not expect any rent payments “any time soon.”

Commercial property co’s like Cominar and Oxford build their individual mall property holdings around cornerstone anchor tenants with large footprints that sign long-term lease obligations. A default on a cornerstone lease agreement could sink the business case for the whole complex, so the companies’ pursuit of their tenant in court makes sense, and the revelation of HBC’s delinquency, while potentially expected in the context of a weak retail sector, was jarring.

The company has been a mainstay of Canadian public life for all of living memory, and several generations before it. HBC not paying its rent has serious down-side implications in the retail and commercial real estate sectors, and the depth of the potential disruption depends on what the company’s governors are up to, and how far they take it.

The dynamics of this particular situation are obscured by a take private transaction executed at the beginning of 2020, but are best appreciated in the context of this 339 year old company’s journey through various different commercial incarnations into its present one as an opaque, developing real estate conglomerate.

Beginnings as a private sovereign

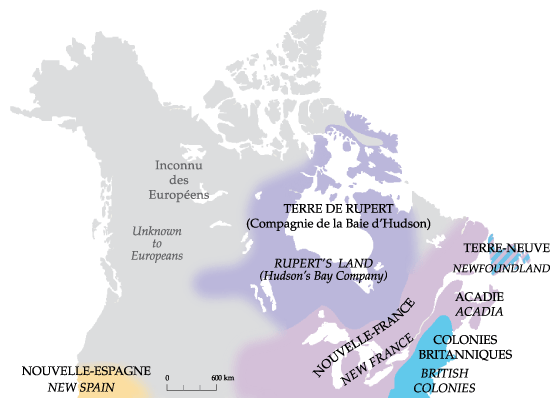

The original Hudson’s Bay Company was a sort of British colonial privateer, taming the great new world in the name of the Crown. King Charles granted the company its original charter along with title to all land in the drainage basin of Hudson’s Bay, named, at the time, “Rupert’s Land,” after its original cornerstone investor, Prince Rupert.

The company established forts and trade lines with native and settler trappers. As it happened, industrial goods like axes and kettles, cheap and plentiful in England, were worth many times their equivalent in fine Canadian furs to be brought home to England’s best furriers. The mercantile company developed rapidly. It had title to wild, undeveloped country, charter giving it a monopoly over its core business, and the de facto first call on the business that surrounded it.

The company expanded West and opened up new territory. When rival chartered merchant The Northwest Company began competing in the 1800s, the Crown forced the companies into a merger to quell emerging violence on the frontier, and created in the process a continent-wide juggernaut that built an empire stretching all the way to Hawaii.

1870 – HBC equity first made available to common investors

Hudson’s Bay was allowed to keep the land under the trading posts it had established when Rupert’s Land was decreed to the newly formed nation of Canada in 1870. The land would develop into the downtown cores of modern cities of Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton, among others. With the burden of running a de facto government unloaded, the company was free to devote resources to real-estate speculation in the rapidly expanding new country. It bought more land and improved it by building stores capable of supplying all the material goods that the growing nation could consume.

The department store empire that burgeoned on the back of that foothold enjoyed growth along with the nation it preceded. Even as the department store business became hyper-competitive in the post-war industrial expansion, The Bay remained a mainstay in Canadian life. It supplied remote rural areas through mail order, and used its prime real-estate in urban centers to maintain hubs in supply and logistics networks that benefited from centuries of institutional memory.

When the company issued its first public stock in 1870, it was to investors interested in the speculative value of the prime real-estate controlled by the company, and the speculation worked out. The population centers around the stores grew and thrived. The company grew the equity in that real estate portfolio into an empire. It owned chains of department stores in the high-end, mid-market and discount tiers. Hudson’s Bay owned oil and gas holdings in the 1970s, and did the sort of thing that is generally done with generational, un-beatable piles of wealth: whatever it wanted.

2012 – First stock exchange listing

Hudson’s Bay Co’s modern incarnation as a public company began in 2012, following its purchase by department store magnate Richard Baker, and his family’s private equity firm, the National Retail Development Company.

The NRDC owns department stores, but makes much of its business out of the ownership, management, and leasing of commercial real estate upon which those department stores operate, like Oxford Properties and Cominar. If 2012 seems like an ill-fated time to get into the physical retail business, it’s because it was. As brick and mortar retail died its slow death, the Baker family put a bit of faith in the staying power of luxury retail, especially luxury retail clothing.

The NRDC made HBC the centerpiece of a portfolio that included the Lord & Taylor, and Sachs 5th Avenue brands, eventually consolidating them under a new-look HBC with throwback branding that celebrated its colonial roots. Hudson’s Bay Corp IPO’d in 2012 at a $2 billion market cap.

2015 – Adventure on the continent

Hudson’s Bay’s adventures in Europe were a failure in terms of retail operations, but a success in terms of real estate investment. A 2015 joint venture in a German property portfolio resulted in a $159 million gain when HudBay sold it to its Dutch partner SIGNA in 2019, then swiftly dissolved the Netherlands-based retail part of its partnership with SIGNA in what may have been a preview of the HBC strategy we’re watching unfold in Canada.

The Dutch real estate company sold its interest in HBC Netherlands, along with $652 million in operating liabilities, to Hudson’s Bay Corp. for a nominal price of 1 Euro, at which point Hudson’s Bay promptly defaulted on the Dutch leases, walking out on $379 million in lease guarantees.

Hudbay’s disclosures are clear about the shuttering of HBC Netherlands not affecting North American operations. Without title to any assets in the Netherlands, the landlords’ use of the courts to recover the lease guarantee isn’t likely to get far. Meanwhile, plans were already afoot to move the North American assets off the public markets.

The chart of the total market cap showed the total equity value in HBC ending up $600 million ahead of where it started as a pubco in 2013, but not all equity is created equally.

HBC sold $500 million worth of preferred equity to private equity firm Rhone Group in 2018. The preferred stock earns a 5%/year equity dividend, and was worth $623 million when HBM went private, leaving the common shares about where they started, value-wise.

The Go-Private Transaction

As retail modernized, moving online and making a modern giant out of Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), Hudson’s Bay mostly failed; stubbornly trying to use its weight to carve out a legacy niche in high-end retail. The cashflow never came and the street quit waiting around for it. Increasingly, investors clamored for a piece of the real estate value that had been built over three centuries or, at least, what was left of it. It was starting to look like a waste lumped in with a series of money-bleeding department stores.

After no small amount of fighting about it, a deal was struck to buy the minority shareholders out for $11 / share in January 2020. Technically, the minority shareholders had their stock purchased by the company itself and cancelled, leaving the remaining shares to a conglomerate of controlling shareholders under the banner of a Cayman-Islands-based entity called L&T B Cayman.

Hudson’s Bay Corp. ceased to be a public filer in March of 2020, so it’s unclear what Canadian assets are still owned by the Canadian corporate entity.

The conglomerate included, either directly or through affiliated holdco’s; Rhône Capital LLC, Hanover Investments, Abu Dhabi Investment Council Company PJSC, Abrams Capital Management, and Rupert Acquisition LLC, a company controlled by Richard Baker.

The early warning report that lays the arrangement out names a laundry list of joint actors that include various trusts and subsidiaries of the shareholder group, as well as We Work and its numerous subsidiaries and holdcos, further indicating that the company may have plans for the real estate it owns in Canadian cities other than operating it as department stores.

In February of 2019, there was $3.8 billion worth of property plant and equipment on Hudbay’s balance sheet, much of it prime urban real-estate, waiting to be developed. The downtown Winnipeg location that was once the hub of a burgeoning and expanding western frontier will be closed this coming February.

Should the company elect to get out of the department store business, the $318 million worth of lease obligations aren’t the only liability starting to look like an un-necessary expense.

The sharp drop in employee benefit and pension liability between 2018 and 2019 was due to the same European divestiture that saved Hudson’s Bay $318 million in lease obligations. $515 million worth of pension and benefit contribution liabilities have presumably become the problem of the owners of the remaining German stores and, in the case of the former Hudson’s Bay operations in the Netherlands, nobody.

The pension liabilities are backstopped by pension assets and, with the European liabilities gone, the accounts were basically even at the beginning of 2019. But should Hudson’s Bay elect to pocket the pension assets and quit funding the liabilities, the employees may have to file suit in the Cayman Islands if they’re hoping to secure a lien against anything of value.

The World has Moved On

As absurd as it may seem, retail sales has never been the core business of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The retail sale of goods was the activity that best lent value to the land the company owned in the 20th century, just as the operation of a merchant monopoly was the best way to pay off its land holdings in the 17th though 19th centuries. An earnest adaptation of the well-established logistics network and enormous consumer base to succeed in the 21st century was never attempted by HBC, potentially because management couldn’t imagine fitting such a business around its land portfolio.

In March of 2020, all that was left of the company that once had the power of a nation state, and all the value that went along with it, was $2.6 billion in beat up stock that reliably lost half a billion dollars per year. The value built over three centuries hadn’t been squandered, so much as extracted by the company’s various pre-public owners.

As the market failed to produce an attractive multiple, its current owners have shuttered the proverbial store windows and begun renovating whatever is left into whatever they expect will best suit it in the coming century without the burden (and audience) of public filing requirements. The dismal performance of the REITs they appear to be in the process of stiffing suggests that it will be something other than commercial retail.

Information for this briefing was found via Sedar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.