New Found Gold courts controversy as it does the detective work, and The Deep Dive’s crash course in mineral sampling.

New Found Gold (TSXV: NFG) became a mining market-darling in the spring of 2021 when impressive high-grade core widths from its Queensway gold project near Gadner, Newfoundland started to stack up and make zones of themselves. Since then, the company has been going at a couple of known gold vein systems hard.

The eight rig, 200,000 meter drill campaign undertaken (which since doubled to 400,000 metres) is front and center on the company’s home page with a highlight reel of the eye-popping grades and widths that the program has produced to date. The work has looked great on the news feed for the past year.

Mining investors have a lot of time for a gold company that is objectively onto something, can use its progress to raise more money, put that money in the ground, make more progress, have that progress drive the share price, attract name brand partners like Sprott and Novo Resources Corp. (TSX:NVO), put their money back into the field program, produce more results… That kind of pace and trajectory is what dreams are made of. As far as gold investors were concerned, this baby was a thoroughbred.

But then, trouble.

A November 4th press release reports that independent consultants hired by the company to look into the quality assurance and quality control aspect of the sampling program in place at Queensway had identified inconsistencies between the grades of the core sent away to the lab to be assayed, and the grades of the matched core held for QA.

Upon publication of this news, New Found Gold immediately lost $204 million in market cap on 2.6 million shares of volume, its biggest day all year, as it saw the swift exit of investors who would rather just sell the stock and not have to care, instead of trying to figure out what any of this means. For those of you who are curious, married to the trade, or just can’t help themselves, The Dive has you covered.

The Sampling Process

Mineral exploration is a science, and science requires controls. So, when a company takes diamond drill core samples in the field, those samples are split in two, usually with a saw. One half of the core is then sent to the lab for assay, and the other half is kept by the company, on site or at a company facility, to be used as part of the verification process. It’s always been best practice to do it that way, but the advent of National Instrument 43-101 codified the sampling process prescribed by the Canadian Institute of Mining in the late 1990s, and required a Qualified Person to be responsible for its practice by mining companies, fast and loose sampling procedures having made it a bit too easy to commit securities fraud with a gold company.

Mining companies listed in Canada are required to outline their sampling procedure in all of their exploration-related news releases, and describe it in further detail in the technical reports. The exploration team at Queensway are logging and splitting the diamond drill core at a company facility in Gander, Newfoundland. It looks like they’re taking two meter samples, sawing them in half, sending one half to the lab for assay, and keeping the other half on a rack at the shed for safe-keeping.

They’re also including blanks (junk samples that should return zero) and standards (samples of known values) in with the samples sent to the lab at regular intervals, as a part of the QA/QC process. The process described in the company literature reads like the standard practice prescribed by the CIM, and leaves the reader with the impression that this team is thorough.

Fire Assay For Precious Metals

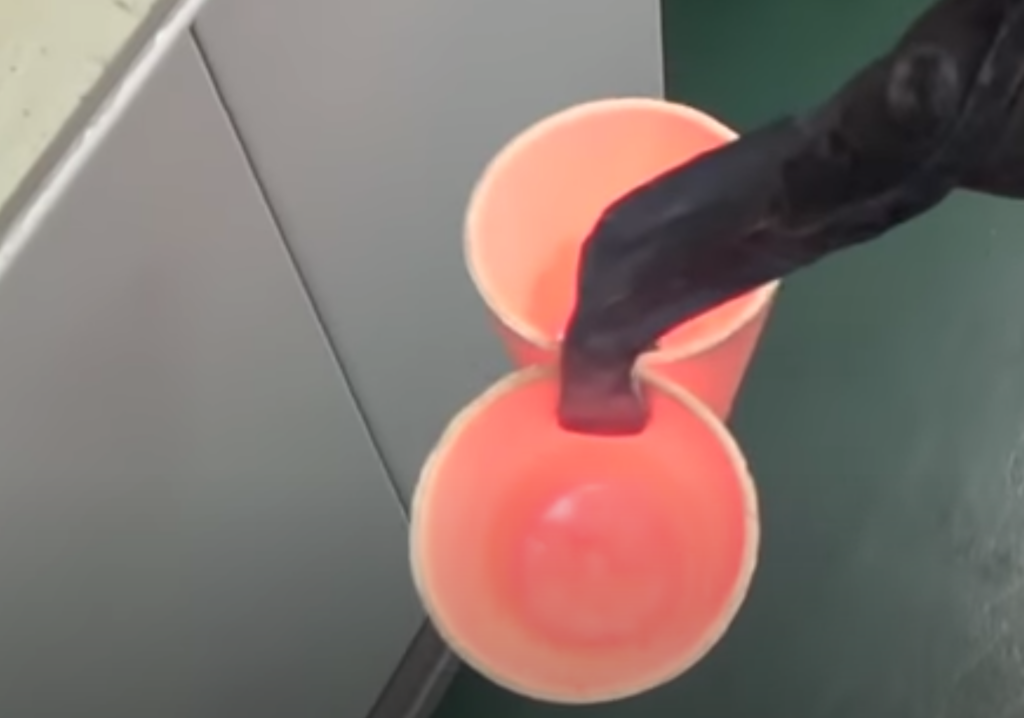

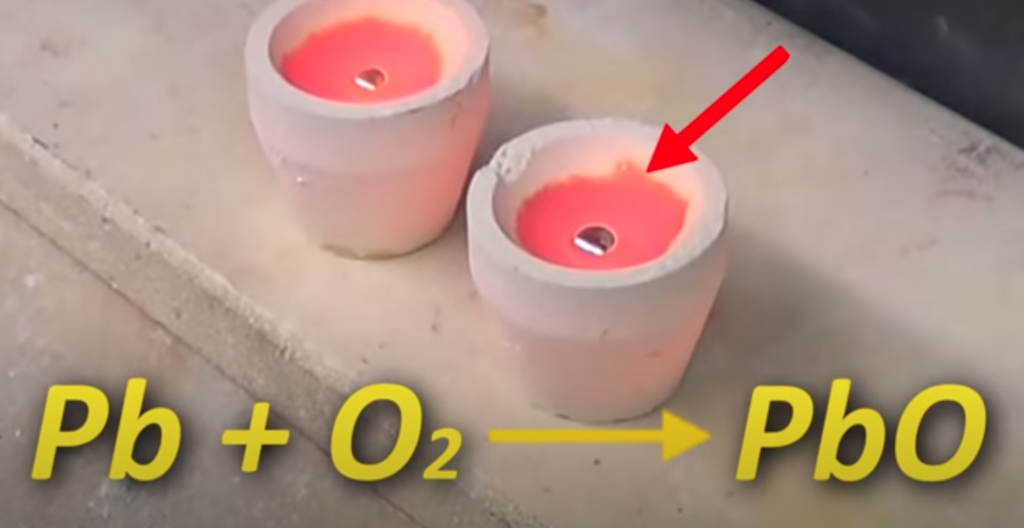

When the samples arrive at the lab, each individual sample is crushed and riffled such that the drill core half, which showed up as a piece of rock, becomes a pile of homogenized dust called a “pulp” that can pass through some specified gauge of mesh. When conducting a fire assay for gold, the lab takes a small sample of that pulp (30 grams in this case), mixes it with some dry reactant chemicals, and heats the mixture up in a crucible until it all fuses together into a glass-like puck called a “slag.” When the sample cools, the precious metals that were in it end up collected in the lead that was mixed in the dry mixture in an alloy at the bottom of the slag.

That lead-gold-silver mixture is then heated up again in a more porous type of container called a “cupel.” During the “cupellation” process, the cupel absorbs the lead, leaving the precious metals that were in the sample in a small bead.

All images of the fire assay process were grabbed from this video, courtesy of The International Precious Metals Institute, whose explanation is much more detailed than the simplified version we’ve presented here.

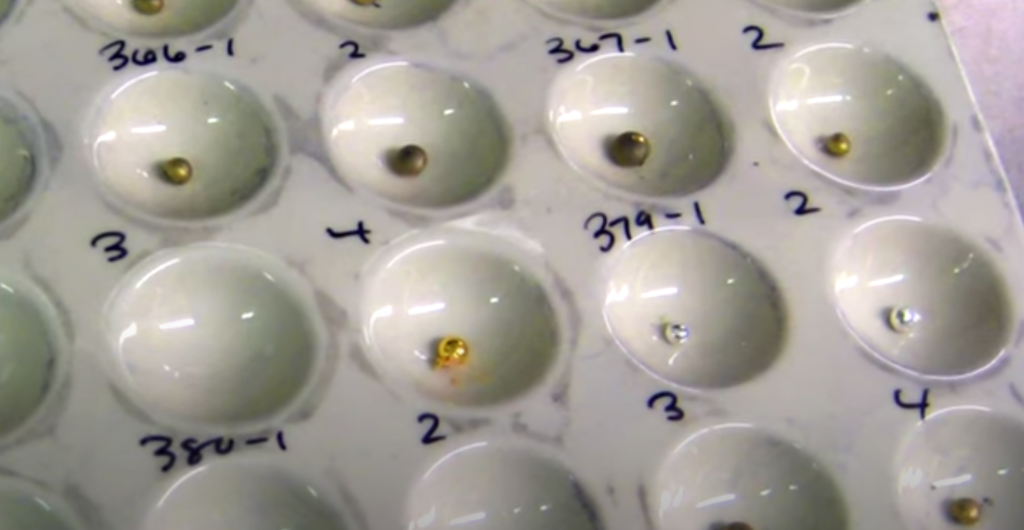

That bead is then further analyzed and weighed, and its mass expressed as a portion of the mass of the original sample that was put into the crucible to yield the “grams of gold per tonne” value for that particular core sample half, for use in the model as the value of the core length represented by that sample, at the depth it was retrieved.

The Nugget Effect

Naturally occurring gold likes to stick to itself and form nuggets. Since gold is supple and malleable, nuggeted gold resists the crushing and milling of standard sample prep when there’s enough of it and ends up scattered through the sample pulp in chunks, rather than mixed in with the kind of homogeneity necessary for a representative sample. To control for this, field geologists flag the samples that contain visible gold for metallic-screening assay: a more involved process that pulls the metallic elements out of ground samples, and subjects them to their own lead amalgamation, cupellation, and analysis.

Separate assay of the metallic elements of a sample is a more time consuming process, but it’s necessary for an accurate picture of the gold grade of any sample that contains gold nuggets large enough to be seen by the naked eye.

The information returned to the exploration team when the assays are completed is the assay-tested grades of each two meter core sample. After confirming that the standards and blanks came back as expected, the team goes about putting sample grades together in spreadsheets, determining what the rock they sent to the lab tells them about the gold zone they’re working on, and writing a news release.

The Issue

New Found Gold’s sampling and quality control procedure has all the appearances of having been designed by engineers who take their craft seriously. The team built check sampling of the control core kept back at the shed by an independent consultant into their process, and that independent consultant’s findings are what is causing all of this commotion.

According to a handy scatter-plot included in the company’s November 4th press release (are these guys engineers or what?) 22 of the 30 check samples assayed by the independent consultant for verification returned assay grades that were below those of their originally sampled counterparts.

This desk does not have the background to comment on the overall significance of this particular variance in sample values, but does note that the widest variance appears at the very top of the sampled grade range.

What Happened?

Clearly, the process broke down somewhere. It could have something to do with selection bias in the field (a geologist consciously or unconsciously selecting the sample-half with the most visible gold to be sent for assay), or selection bias at the lab (a technician consciously or unconsciously selecting a gold-rich 30 grams out of the milled and rifled sample). Or, it could be a technical issue: a field geologist failing to flag all of the nugget-prone samples for metallic screening, or a problem with the sampling process at the lab itself.

New Found Gold has embarked upon a plan to identify the source of the discrepancy by first ruling out lab bias or lab error. That process involves sending identical samples to the two labs that were used for assays to date, comparing the results, and using a third “umpire” lab to check discrepancies.

If lab error can be ruled out, the company plans to address an obvious field error with a mass assay of the check samples, and averaging of those results with the results of their original sample counterparts, because the show must go on.

A November 8th news announcement told the market that NFG plans on switching labs and assay processes whether it turns out the lab made an error or not. They’re moving to whole-core sampling via the Chrysos PhotonAssay ™ method, a process used to great success by NFG shareholder Novo Resources on nugetty samples in Western Australia. The company is working on an agreement that will see the process undertaken either in Gander or in Val D’or, Quebec once suitable facilities are built but, for the time being, the plan is for core from Queensway to be shipped to Perth, Australia, where Novo has arranged for its priority assay by the new method.

Market reaction to the company’s decisive action on its lab process going forward was tepid. NFG was off -$0.70 (-8.7%) Monday on 1 million shares of TSX.V volume, to close at $7.34, investors apparently failing to see the same promise in the Chrysos PhotonAssay ™ procedures as New Found Gold’s engineers do. Presumably, $1.1 billion is the market value of a New Found Gold that has called its own results into question, and remains dedicated to the integrity of those results.

Once the detective work is done, we’re going to get a look at whether this project is everything it appeared to be in May and June of this year or… something else.

Information for this briefing was found via Sedar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.

4 Responses

Selection bias: Nothing personal, but I would have done the same thing that NFG core samplers did. We all realize that these core assays represent rough estimates of gold content. HOW MANY gold companies do exactly what NFG did? I see nothing wrong with this process; again, these assays represent rough approximations of the existence of gold deposits. A 1 oz assay may return .5 oz if it becomes commercial mine; or 1.2 ounces. I would not expect this 1 ounce assay to be anything more than a rough approximation of the potential existence of a commercial gold find.

I do hope that NFG shares remain low; it enables me to add additional shares. I’m still BULLISH on NFG. They were honest and disclosed what they did – a rare occurrence. It tells me that mgmt. is honest and willing to demonstrate it’s intent.

The length and width of NFG’s assays will prove that this is still an extremely viable gold discovery. Nuggerty gold can influence assays; but whose to say if the entire cores may contain nuggety gold that is not visible in the core.

Maybe NFG should have disclosed this. However, they were not trying to hide it from the public. It appears that the assays represented part of an ongoing Q/QC type project.

Your comment was good, Braden, but more us involved, which everyone should know about. Whey we are dealing with really high grade ore-grade zones with abundant visible gold, the distribution of gold is not equal on each half of the core, so per force they likely will not be the same. I worked on these problems at the Homestake Mine with metallurgist Richard Kunter. Assaying the entire core by screen fire analysis followed up with 5 assay ton samples of the tails is the way to go. Or, jig and table and tail-analyze all of it. Hopefully the Chrysos process will be short-cut the time off of these laborious procedures.

Sincere thanks for reading, Rick.

Looking back, one might say that the information on the nugget effect being presented here ended up concentrated in one particular section, and resisted an even distribution throughout the post.

For those looking for more information, there’s a pretty good coles notes version of the nugget effect here:

https://labs.seprosystems.com/what-is-the-gold-nugget-effect/

And a more detailed paper here:

https://geostatisticslessons.com/lessons/nuggeteffect#:~:text=The%20nugget%20effect%20is%20a,function%20(Morgan%2C%202011).