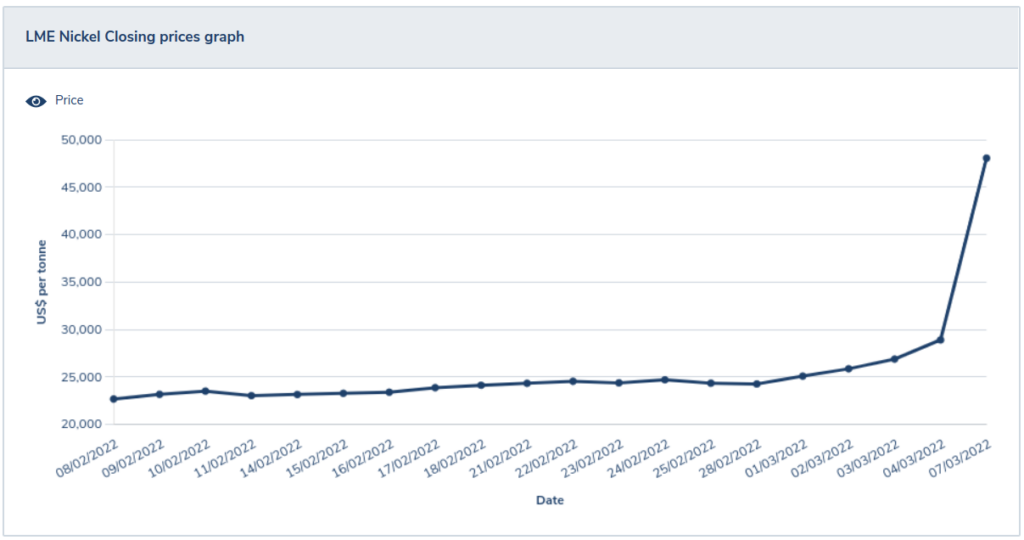

The London Metals Exchange has closed trading in nickel contracts until future notice, and will be cancelling trades from March 8th, 2022, following an unprecedented short squeeze that took the price of nickel from $25,400/tonne to $29,750/tonne in three trading days, then to $42,995/tonne on Monday, before intraday trading on Tuesday took the price beyond $100,000/tonne on trades that will now be cancelled.

It will likely take a couple more news cycles to flush out the details, but all accounts have this price move down to Chinese nickel producer Tsingshan Holdings Group (private) having to cover a massive short position at a loss, and the market piling in and making a GameStop of it.

Tsingshan is a private Chinese stainless steel producer that made its mark in the metals industry through the application of clever metallurgy. It appears to have put itself in this jam by getting even more clever and betting they could do it all again. To understand this situation, we first have to understand that:

Not all nickel is created equally.

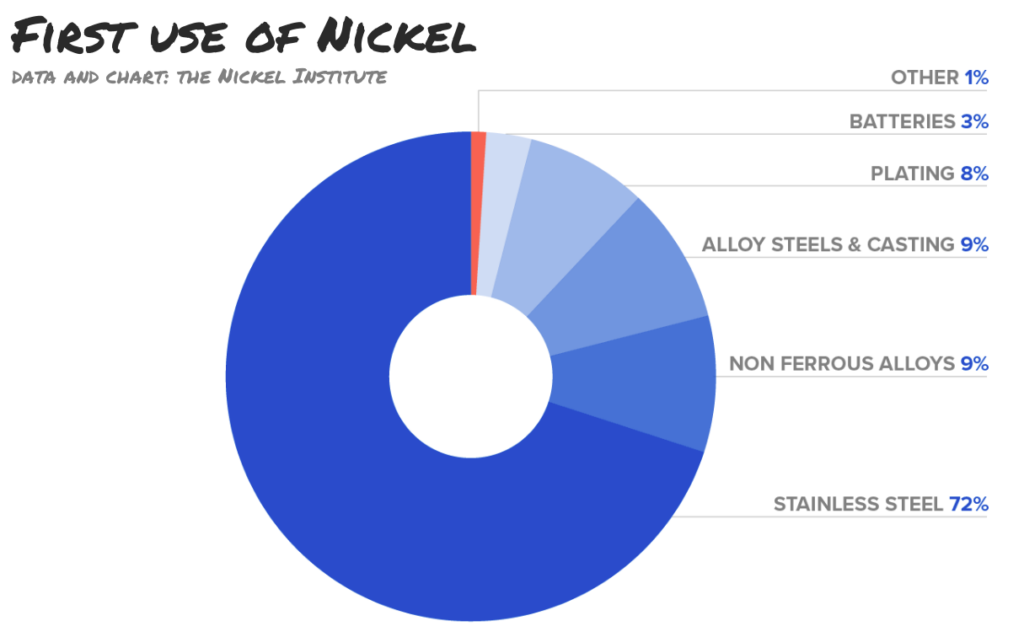

Nickel’s primary use is in alloys, especially stainless steel, but also in the electroplating of handguns, and increasingly in batteries, which we’ll get to. It’s sold, industrially, in various different types of bulk configurations, the purest of which is the high-grade that is traded on the LME, and housed in various LME warehouses where the buyers and sellers can take or make delivery of nickel bought and sold via contract on the exchange. LME warehouse nickel is available in various shapes (cathodes, briquettes, rounds, etc.), but is always pure, raw, uncut >99.8% Ni, straight from the smelter.

But not everybody needs the high-test. Buyers who are planning on using nickel in ferrous alloys like stainless steel are going to smelt it with iron of some kind anyhow, so a bulk product consisting of 25%-35% nickel, 65-75% iron, and a pinch of cobalt is just fine with them. Such concentrates became popular in the 2000s, when companies started making them out of bulk tonnage laterite mines.

Laterite is a leeched-out reddish rock usually found in tropical regions, and sometimes used in ceramics or quarried for construction material. It usually has low grades of nickel, iron and aluminum that, when mined in a high enough tonnage, can be used to produce the aforementioned ferronickel for use by stainless steel makers to whom it is ultimately cheaper to use than high-grade concentrates or ingots. Brazilian nickel giant Vale (NYSE: VALE) was built on shipping ferronickel produced from laterite deposits.

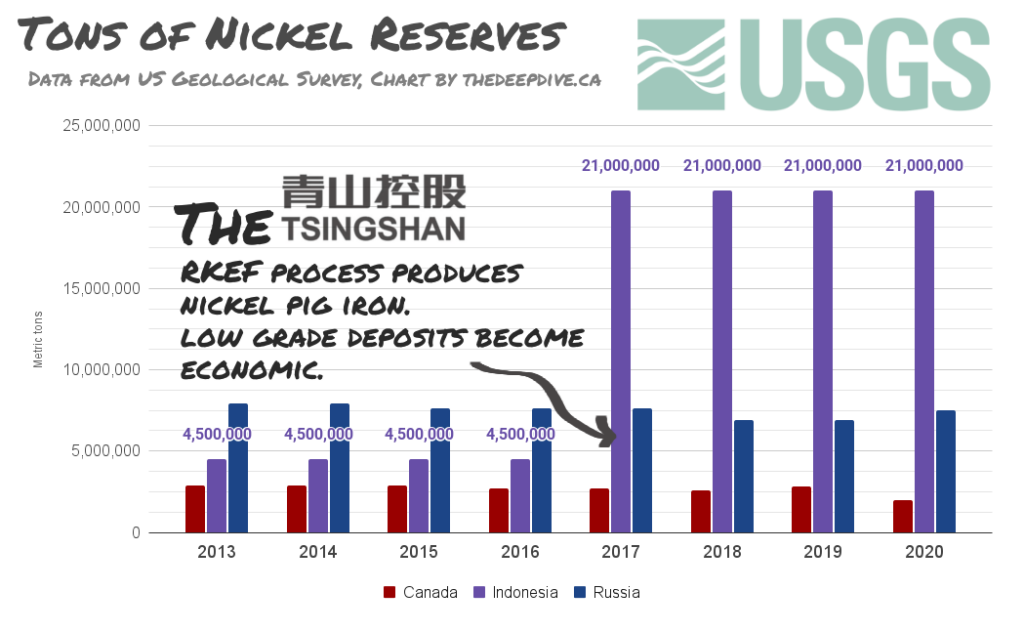

By 2016, stainless steel making Tsingshan, who didn’t see any reason to buy a 25% nickel concentrate product if they didn’t have to, was leading the race to the grade bottom. The company pioneered nickel processing through Rotary Kiln Electric Furnace (RKEF) to produce “nickel pig iron”; a product that contains somewhere between 2% and 13% nickel, and a bunch of other junk, mostly iron, at a greatly reduced cost. The innovation shook up the stainless industry.

Since Tsingshan is a vertically integrated producer that controls its own materials chain, it didn’t need to sell anyone on the relative value of the low-grade product. It just integrated it as an input, optimized the rest of the process, and produced more stainless. A market for the cheap, low-grade smelted bulk nickel product made ore out of previously sub-economic laterite deposits in Indonesia, where the company operated.

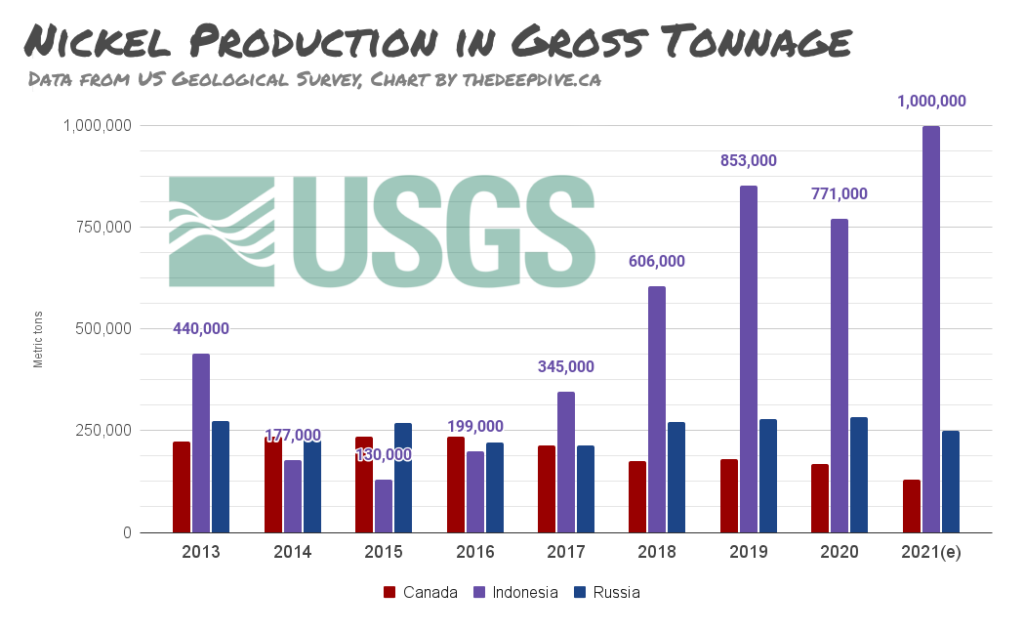

The US Geological Survey has Indonesia’s nickel reserves going from 4.5 million tonnes in 2016 to 21 million tonnes in 2017, as Tsingshan and its partners opened up new low grade to supply the Chinese market. Production out of Indonesia went from 130,000 tonnes in 2015 to an estimated one million tonnes in 2021.

All of that low grade weighed the nickel price down through the 2010s, but the market picked up again in 2018 as the markets took a forward look at the nickel that would be needed for the batteries that store power in electric cars. Nickel pig iron is fine for stainless, but it’s no good for modern battery cathodes, whose production requires the type of high-grade, low-iron nickel sulfides that ship to high-end alloy makers when they can get away with something less than the LME raw. The pending rise of EVs had the nickel price on a tear, but Tsingshan had a plan for that, too.

Taking it to the Matte

In March of 2021, Tsingshan announced a deal to sell 100,000 tonnes of nickel matte to two large Chinese battery makers. The company had engineered a way to further refine the nickel pig iron they’d been producing from Indonesian laterite into a matte product with a 75% nickel concentrate that was apparently an acceptable input for battery production. The announcement caused an 8% drop in the nickel price at the time, and it spent about a year climbing out of that hole, until last week, when it started to show the first signs of Tuesday’s commotion in London.

“Rather disappointing jam you’re in there, Guv’na…”

Most of the world’s nickel isn’t sold on the LME. It’s a clearinghouse that’s mostly there for traders to trade six-tonne lots of nickel that they have no intention of producing or taking delivery of, setting an ever-moving benchmark for private parties to use when when they make deals for delivery of nickel and various other metals. It’s common for metals producers to use the spot markets to forward sell their anticipated production through short positions, effectively locking in a price the miner would receive for the metal it plans to produce before the contract’s delivery date.

If the price falls, the company can close the trade at a profit. A rising price doesn’t matter to a short producer, who can usually cover out of their reserves or production. But the LME has no use for the pig nickel Tsingshan produces, or even the matte nickel they’re selling to battery makers. Exchange delivery nickel has to be The Raw, and that comes from Russia.

Norilsk Nickel (MCX: GMKN) (LSE: MNOD) (presently halted) has made billionaire oligarchs out of a handful of people whose assets are now being seized by Western governments, because it was founded on one of the biggest and richest mining complexes in the world. Norilsk is built around a series of high-grade nickel sulfide deposits in Siberia whose ore contain concentrations of nickel, copper, cobalt, platinum, and palladium that would all make pay grade on their own.

Out of that ore, Norilsk makes and sells briquettes and cathodes of a purity and spec that make them suitable for delivery to LME warehouses to fill open contracts. Because of geopolitical circumstances, anyone who planned on receiving any in the past few days probably isn’t getting any.

If Tsingshan was all set to produce enough volume of its nickel matte product to take the bottom out of the nickel price, it would make sense for it to lock these high prices in through a short position in the spot market. The un-covered short wouldn’t raise any eyebrows among traders at first, because it belonged to one of the largest stainless steel manufacturers in the world, who could surely get their hands on some nickel at delivery time.

But nickel matte might be as pure as the company’s processes can get that low grade laterite ore. There’s no reason for a stainless steel producer to be set up to produce .999 pure cathodes. If a short position opened to lock in a sale price started to run the wrong way, Tsingshan may have planned to cover out of nickel that it had bought from other producers, and found itself in a jam when the largest producer was suddenly cut off from the global financial system.

But Western sanctions against Russia don’t have anything to do with delivery obligations at the LME. If Tsingshan didn’t have the goods, they may have tried to casually close the contracts out by buying it on the spot market. And there’s no reason for the world’s biggest nickel pig iron supplier to be buying it out of the spot market except for that they’re short and can’t cover. At that point, everyone piles in. It’s free money.

Whether Tsingshan would have been seriously hurt by the squeeze is unknown. It may well have been able to scare up some cathodes or briquettes somewhere else for delivery, or may have already got what it needed out of the spot market before the sharks came out. It may have ended up that the momentum traders piling in ended up paying $49,000/ tonne (and rising) for nickel that would soon collapse to a pre-squeeze $25,000/ tonne.

We’ll never know, because those killjoys over at the LME shut it all down and unwound the trades; determined to keep their nice, civilized means of price discovery from turning into a mess of hooting apes.

Information for this story was found via the LME, TradingEconomics, Norilsk Nickel, Tsingshan and the other sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Views expressed within are solely that of the author. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.