The banking sector has largely been slow to join the post-covid recovery, and that’s understandable. Banks represent the rawest of raw exposure to an economy that was staggered by a pandemic, and is still trying to find its feet in the political turmoil leading up to an election. If and when borrowers stop making payments, the lenders are the ones exposed, so it’s a risk-on trade as a sector, and it objectively isn’t a type of risk that the market has an appetite for right now.

Technology names, software, healthcare, telco… these are the sectors of action in the covid-era casino. Banks are low-growth bores. And, as they continue to lag just out of the updraft of this epic stock-picker’s market, the dividend yield is starting to look juicy.

“If you want to make money,” the saying goes, “go into the money business.” Modern banking comes in various different styles and colors, all variations on a core theme: pay interest on deposits, charge more interest on loans.

Modern banks draw other revenue from card services and securities brokerage fees, but the basic model has proven to be an effective means of gathering wealth and fostering broad economic liquidity since it was invented. The wealth is generated so effortlessly that it’s been making people jealous since as far back as that one time Jesus booted them out of the temple.

The advent of securitization allows savers to get in on the banking grift a few tiers down from the central bank epicenter and, as beat-up bank stocks continue to under-perform the market while their revenue and dividends remain largely unchanged, we’re eyeing up those fat yields and wondering if this might be as good a time as any.

“The business of America is businesses.”

Calvin Coolidge

Since the American economy and the world economy both run on debt, the vested interests of powerful institutions and the economy itself revolve around lenders and borrowers continuing their cycle uninterrupted.

So far, the intervention of central banks has prevented mass defaults and, ultimately, that’s something banking investors have come to count on as a downside hedge. Instead of the crude, ham-fisted purchases of underwater securitized debt products for which the market dried up overnight that we saw in 2008, central banks made crude, ham fisted purchases of debt that threatened to go toxic before it had a chance to and, so far, the confidence that intervention it brought on has held.

The defensive measure of backstopping corporate debt was complimented, in the United States, by a stimulus-based offense, executed through the facilities of the nation’s commercial lenders. Forgivable PPP loans were dealt through the banks at their own discretion, because who would know better than them which of their clients is the most in need of a forgivable loan? With an institutional latitude that practically makes them part of the system itself, it’s increasingly difficult for a bank to screw it all up (though it’s foolish to put it past them completely).

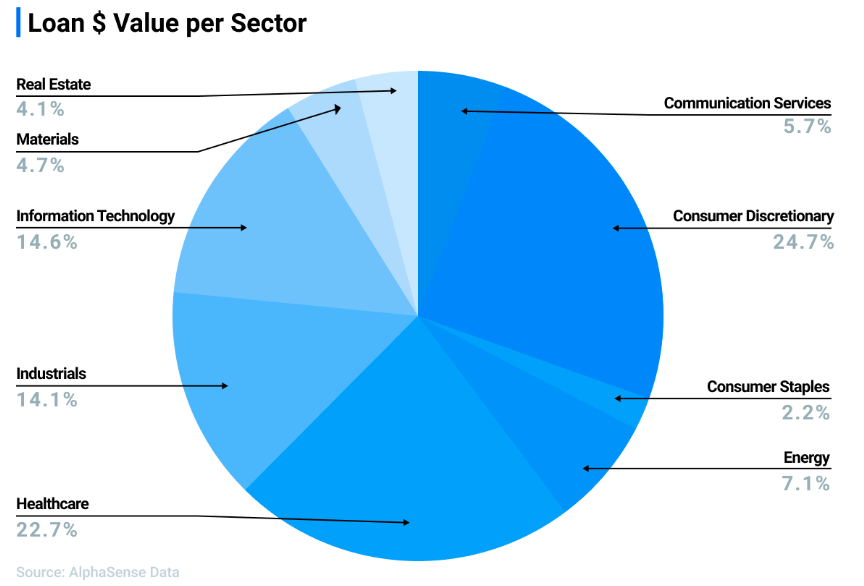

Much like the bond ETFs we were scoping at the onset of the lockdown, evaluating bank stocks themselves starts with an evaluation of their exposure to toxic assets: borrowers that might not be able to service the loan or pay the principle, because the pandemic economy has caused whatever business, income or home equity the loan was staked against to no longer exist.

Unlike the bond ETFs, the banks don’t publish an itemized list of the financial instruments they’re exposed to, but they do give a basic profile of the type of lending they do, enough for a stock picker to ballpark a risk profile. Since the last time investors started to get jittery about the actual value of all this paper and threaten to collapse the whole damned economy, US Congress decided to force US Banks to publish a metric that gives investors an idea of the class proportions of security classes the balance sheet is made of.

The Capital Ratio or Capital Adequacy Ratio is kind of like the nutrition label on food. It can be found in the 10K next to a warning about how it’s no good as an absolute measure of the company’s balance sheet risk. Capital ratios are basically the read out from a stress test, and it’s worth paying attention to, because if a bank comes out of it deemed “under-capitalized,” or “significantly under-capitalized,” as per the FDIC, they’re not likely to fix (or have it fixed for them) in a way that protects the shareholders.

The Dive took a look at bank stocks that have been beat up, and picked a few with big divvies that look likely to stick around for a while based on implied downside protection, and are pleased to pass them along with a reminder that blogs are no place to go for financial advice. Stay tuned.

Information for this briefing was found via Sedar and the companies mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.