Toronto-based economist Will Dunning climbed up on a soapbox over at the Globe and Mail recently to lament the fact that, in this new high-rate environment wrecking the housing market, Canadian borrowers whose mortgages are up for renewal are at risk of being gouged by their lenders.

The rules make it so that a borrower needs to be able to carry a rate 2% above the rate they’re paying (or are in-line to be paying on a renewal), if they want to transfer their mortgage to another lender.

Five years is as long a term as a bank will give on a mortgage, and Dunning’s basic complaint is that borrowers who qualified for a mortgage 5 years ago might just miss out on qualifying for a transfer to a different bank that might offer them a better rate today. Dunning argues that since the average weekly wage has gone up 21% over the past 5 years, there are borrowers who would get better rates if banks could compete for their business, which they can’t, because the borrower’s income fails the stress test at its current rate.

This is as bizarre and muddled a housing-finance complaint as we’ve ever come across, but we’re going to try and graph it anyhow.

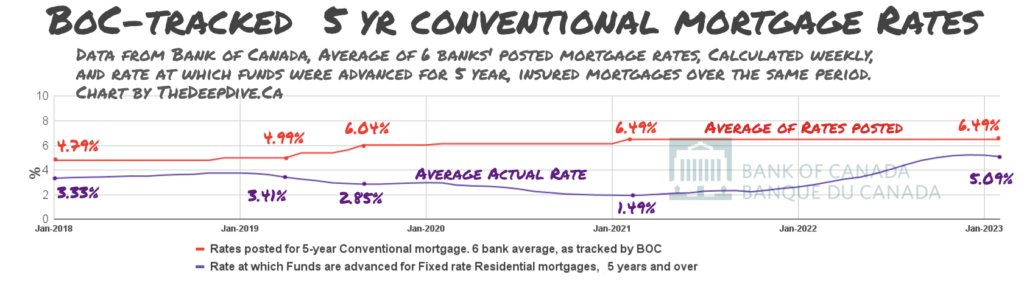

The Bank of Canada tracks the rates at which the banks advance funds for five year mortgages, and the average of the rates the banks advertise for 5 year mortgages, which is consistently higher.

This makes sense, because it keeps away buyers who won’t clear the stress-test rate, and makes the buyers who do qualify feel like they’re getting a deal.

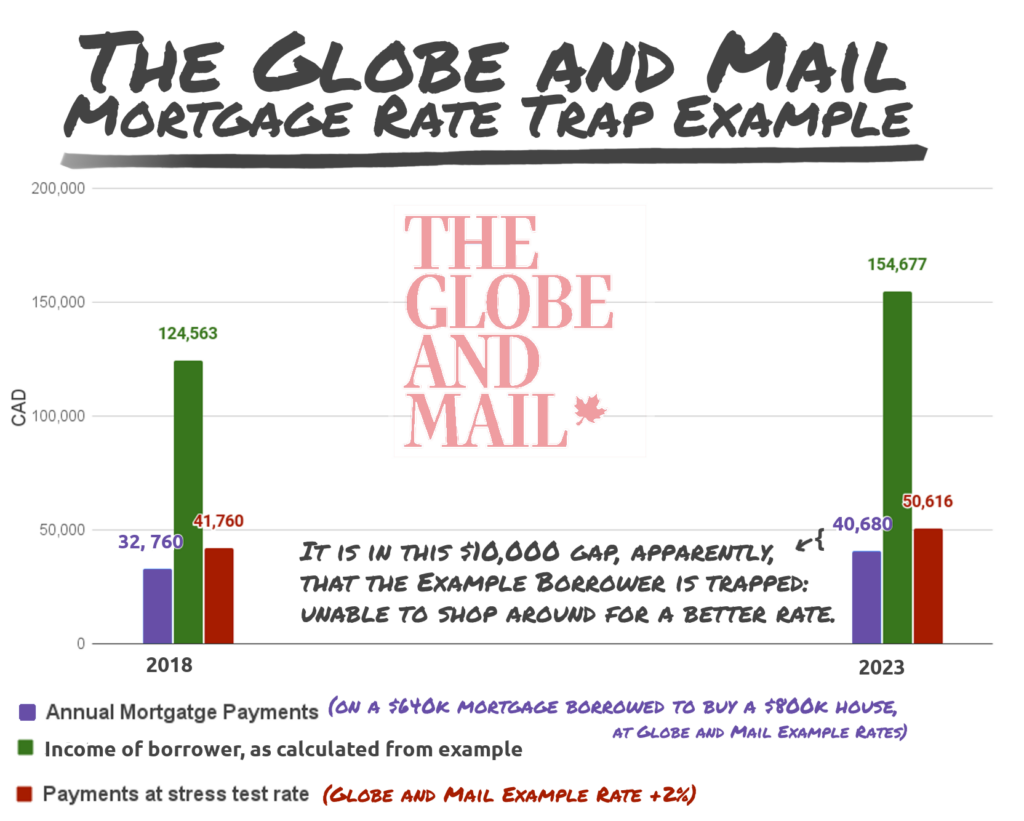

This chart extrapolates The Globe and Mail Example Borrower’s 2018 and 2023 incomes from Dunning’s description of Example Borrower’s payments as a percentage of their income, assuming this fictional borrower bought the same $800,000 fictional house that we used for our own example in the trigger rates and mortgage amortization posts.

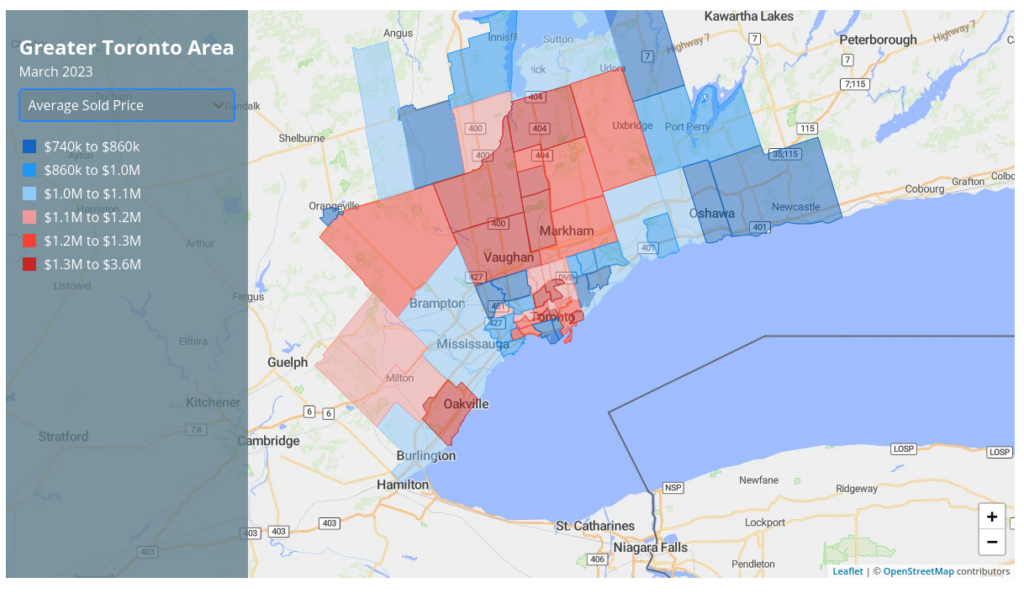

$800,000 might seem like a lot of money for a house, because it is a lot of money to pay for a house, but they hardly ever come that cheap in Dunning’s home town of Toronto right now.

Dunning says that there isn’t enough data to know for sure how many borrowers are trapped behind the stress test rate as he describes, and he’s probably right about that, but we’ll go ahead and assume it’s a significant number of borrowers. The thesis here that the banks’ ability to hold borrowers hostage with a stress test prevents competition that would lower the effective rate might as well be right, too. They might compete if they really had to, and there’s no way to read the banks’ minds. OK. Fine.

But one has to wonder why anyone would even care about that once they got a load of the income and payments in real numbers.

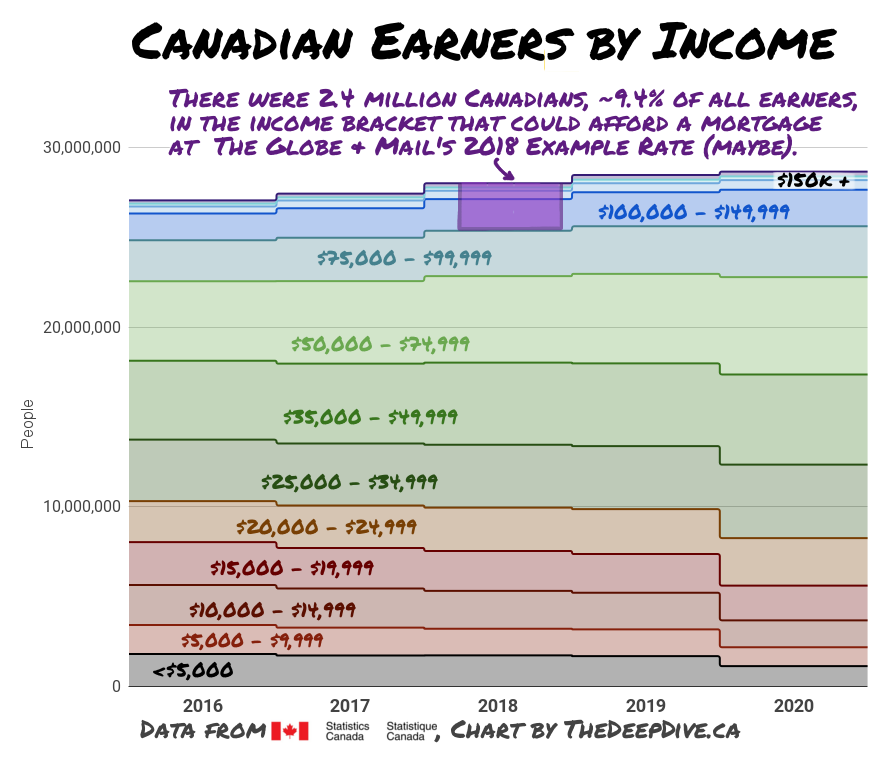

This is a chart of Canadian tax filers by income, 2016 through 2020, the most recent year available. The people who could afford to make these housing payments, in 2018, comprised somewhere between 3.1% and 9.4% of the population.

At the $150k per year necessary to afford a mortgage on a basic home, in basic Toronto, today, only 3.5% of people would be able to afford to finance one on their 2020 income… assuming they had the $160,000 down payment.

Something that literally everyone needs being available as property to less than 10% of income earners, through debt financing, does not strike Mr. Dunning, an economist, or his editors at The Globe and Mail, as much of a structural problem. At least, not as much of a structural problem as the borrowers not being able to shop around for a rate.

And, for all we know, they’re right. It’s called “the housing market” because it’s an organ of finance. If it was there to keep a roof over everybody’s head, it would be called “the housing allocation.”

People concerned about this particular cornerstone of the economy not falling apart can count about as well as the rest of us can, and know that, ultimately, the only thing that pulls a market out of a nosedive is buyers which, at these prices, are in short supply. Canning the stress test rules would undoubtedly qualify a few more buyers. Whether it would be enough to help prices find a floor is anyone’s guess.

It wouldn’t pull our Example Home across any income brackets but, as we keep trying to explain, this doesn’t have anything to do with how many people can afford to borrow to own a home. It has everything to do with how many wealthy people elect to invest their money in homes, and charge people to live in them.

And, to that end, Mr. Dunning has addressed his column to a certain wealthy Canadian who makes an unknown (but presumably large) sum of money doing just that, and who has tremendous influence over the country’s housing and banking policies.

She also happens to be an old friend of this column.

Stay tuned for our next housing episode: Chrystia Freeland-lord.

Information for this briefing was found via The Globe and Mail, Bank of Canada, and the sources mentioned or linked. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.