This is a story of how a kickstarter campaign created a product that turned into a $50 billion company, that today has lost 95% of it’s value from all time highs. Were talking about Peloton.

It seems silly at first. Selling a bike or a treadmill with an iPad so that people could train from home, but feel like they were part of a fitness class. But as COVID hit, this stock went bananas. People were stuck at home and wanted an alternative to the gym. Peloton quickly became the McDonalds of home solutions. By Q4 of 2021, they hit over $1 billion in revenue and saw subscription revenue boom 140% from from 2020 to 2021.

Yet, the company never really made money, and it didn’t matter. Wall Street loved the top line growth and believed that operating leverage would open up rapidly as they continued with their extreme growth.

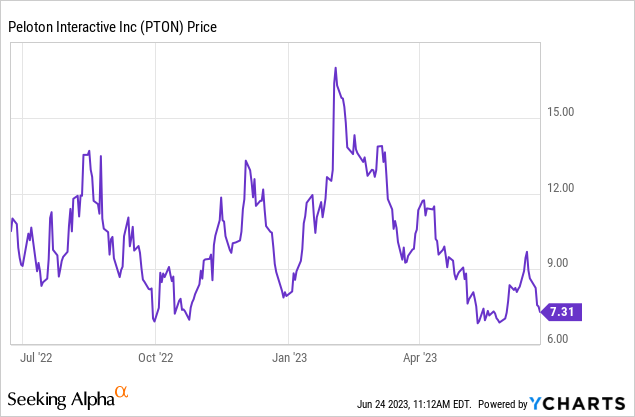

But by 2022, gyms started opening up again. The company had spent massive amounts of money ramping their supply chain just as people realized they didn’t need their Peloton machine anymore. Suddenly the stock lost 95% of it’s value from all time highs.

Today were going to dive into the story of Peloton.

The Kickstarter

Peloton’s genesis can be traced back to John Foley, who was an enthusiast of instructor-led fitness classes and realized that, after becoming a parent, it was increasingly difficult for him to attend these classes. The inspiration to bring the excitement and energy of these classes to the comfort of one’s home led Foley to envision Peloton.

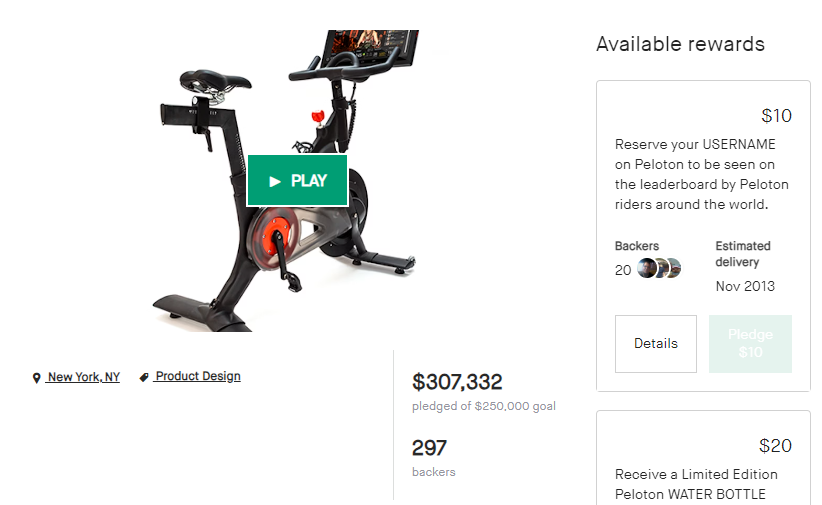

He imagined Peloton as a platform that could offer immersive, instructor-led fitness classes that could be attended remotely through high-end bikes equipped with screens, leading to the first prototype in 2013, which was launched through a kickstarter campaign.

While the product was rudimentary, the kickstarter campaign was a success, enabling consumers to reserve an early edition for as little as $1,500. The campaign saw a total of 297 backers support the company, raising gross proceeds of over $307,000, surpassing the $250,000 goal.

But this was just the beginning.

The early days of Peloton

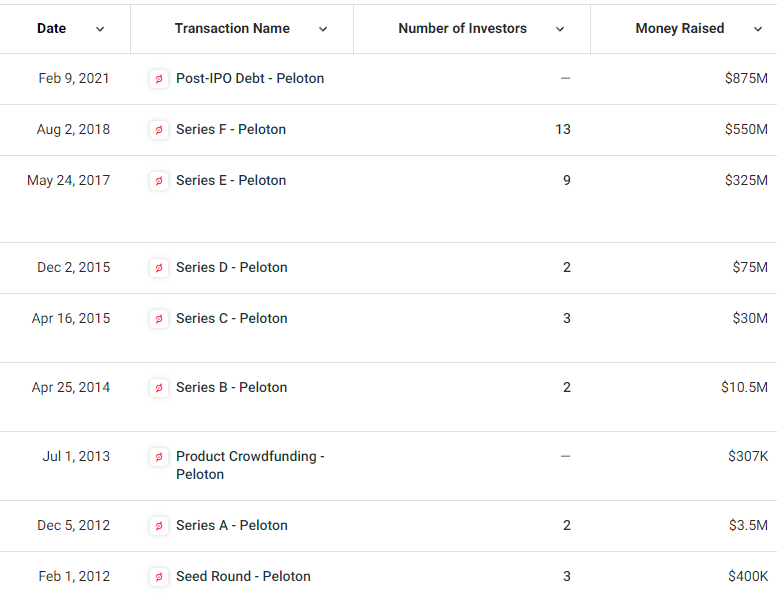

The kickstarter was enough to give Peloton the boost it needed to begin manufacturing its product. A year later, it was followed by a $10.5 million Series B funding that was pivotal in refining the bike’s design for consumers.

The company initiated selling bikes at a modest pace. However, a key challenge that emerged was the efficient and speedy delivery of bikes to customers. But this was the mid 2010’s and money was cheap. So how do you fix a problem? You raise $30 million in a Series C.

The Series C funding allowed the company to establish retail locations and expedite bike production. Peloton meanwhile resorted to an innovative solution of hiring delivery personnel to transport bikes directly to the consumers.

Peloton’s growth trajectory was remarkable. In 2017, it became a unicorn, crossing the $1 billion valuation mark. A year later, this valuation quadrupled after securing a massive $550 million new round of funding.

The company became an overnight success, selling over 400,000 bikes by 2018. The sales model included a $39 monthly subscription to an app that streamed exercise classes directly to users home, garnering it a dedicated and fervent upper middle class user base. Peloton reported that it had a retention rate of 95% for its connected fitness subscriptions, which the company regarded as “engaging-to-the-point-of-addictive.”

The success led to the launch of The Peloton Tread, a, get this, $4,295 treadmill.

By September 2019 Peloton was public, with the company conducting its IPO with a valuation of $7.7 billion.

The pandemic

And then, a pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic spurred a seismic shift in Peloton’s business as stay-at-home measures propelled demand for home fitness solutions. With gyms shut down, individuals pivoted to home workouts, turning Peloton into a household name.

However, the sudden boom in demand presented significant supply chain challenges. Customers faced long delivery waiting times, and Peloton struggled to keep up. In a bid to augment production capacity and reduce delivery times, Peloton acquired fitness company Precor for $420 million in December 2020.

This was shortly after unveiling Peloton’s newly designed Bike+ and Tread. The Bike+ had a slightly larger touchscreen and a better sound system. In an effort to capture a wider range of consumers, the company continued to sell its first generation products at slightly different price points.

By the end of 2020, over 1.7 million households had Peloton equipment, with 1.6 million members having a connected fitness subscription. This allowed Peloton’s revenue to grow 140% to $3 billion.

This growth did not go unnoticed. Investors wanted a piece of the pie, and no price was too high for Peloton. The stock that IPO’d at $29 in 2019 was now close to $170, an insane 440% increase in just under two years, valuing the company at an eye-popping $50 billion.

Despite the growth, demand didn’t stop – likely due to all the free money floating around.

As Peloton continued to struggle with inventory, they announced plans to build a $400 million state-of-the-art manufacturing facility, Peloton Output Park, in Troy Township, Ohio. Alongside ramping up production, Peloton strived to expedite deliveries by allocating an additional $100 million to airship products, a move that was internally regarded as contentious.

Management expected demand to last for years.

The demand shift

Six months later, things started to slow suddenly. The first set of vaccines started to roll out, and companies were eager to reopen their doors to customers.

This was evident in the companies monthly subscriber churn, which went from 0.3% of the total subscribers during the early days of the pandemic, all the way to a 1.4% monthly churn during the summer of 2022. This was a major shift in consumer demand for Peloton and one they were not used to. The company began slashing prices to spur demand, dropping the price of its first-generation equipment by an initial 20%.

The decision was indicative of the company’s effort to remain competitive as gyms reopened and the post-pandemic world began to take shape.

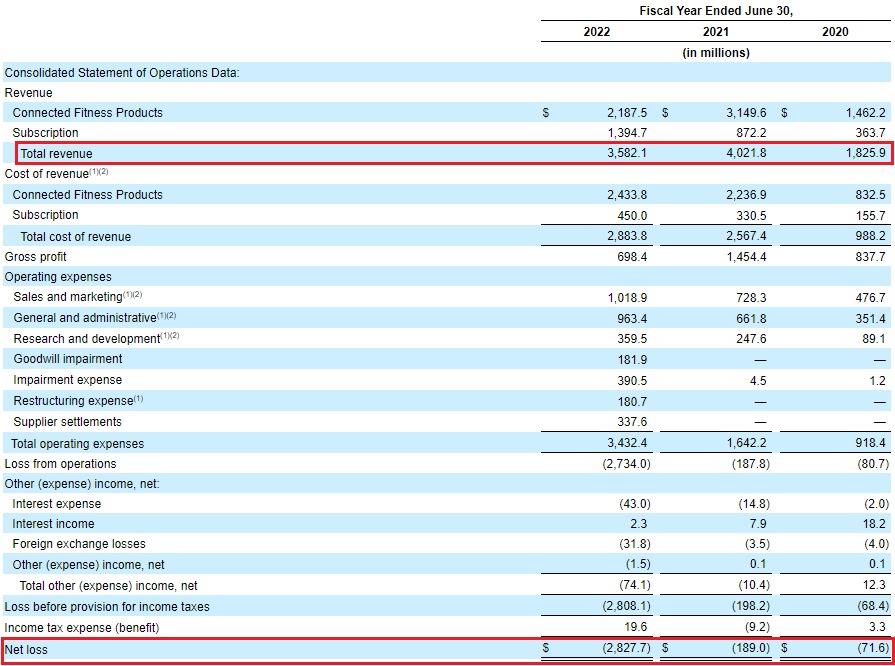

Amidst the operational whirlwind, the company’s financial health experienced a rollercoaster. Despite a meteoric rise in revenue with sales exceeding $4 billion by the end of 2021, net losses climbed despite its subscriber base climbing to over 2.8 million consumers.

This financial turbulence did not deter extravagant expenditures. For instance, Peloton’s CEO John Foley purchased a $55 million estate in the Hamptons. This beautiful house is located near the beach and faces the water with more than 400 feet of water frontage. Not to mention the location, which is on Further Lane, one of the best streets in the Hamptons and making him neighbors to the likes of Jerry Seinfeld, Lorne Michaels, Carl Icahn, and Howard Schultz.

The end of ZIRP

As we stepped into 2022 and the pandemic began to subside, Peloton experienced a significant reduction in consumer demand for its connected fitness equipment.

The $420 million acquisition of Precor two years earlier proved to be all for naught when in an attempt to control costs, Peloton decided to temporarily halt the production of its bikes and treadmills. Production of the Bike+ was halted for seven months, while the original and cheaper Bike saw a two month halt.

Not long after, Peloton announced it would be cutting 2,800 jobs in an attempt to address mounting financial strain. And that facility in Ohio? With not enough demand at current production levels, the plan for an additional manufacturing facility was scrapped entirely.

Beleaguered Peloton Takes Steps To Unload Warehouses, Stores and a Big Vacant Factory https://t.co/pP0vC9QPpU pic.twitter.com/p5pzJR2bu3

— Jason Crimmins, CCIM, SIOR (@jasonmcrimmins) August 26, 2022

And is customary with all sinking ships, management was shaken up. CEO and co-founder John Foley moved to the executive chair role, while former Spotify CFO Barry McCarthy would be taking the helm to attempt to right the ship.

But a new face of the company doesn’t mean the challenges suddenly end. Peloton faced inflation and supply chain issues, which forced them to hike the price of its flagship bike.

This was short lived however, when in an attempt to stimulate sales, Peloton reduced the price of its original Bike for the third time in a year and its higher-end Bike+ for the first time. To combat the expected revenue hit, the company increased its monthly subscription fee for the first time in eight years.

But the damage was already done. Searching any online second-hand shops like eBay would turn up hundreds of listings for Peloton bikes at much more reasonable prices. With Peloton going as far as partnering with eBay to launch a “Certified Refurbished” program that offered Bikes for a $500 discount off MSRP. Meanwhile, the company was seeing its products gather dust in warehouses as inventories ballooned to over $1.5 billion dollars. Now that’s a lot of $4,000 treadmills.

The repercussions of these missteps were severe: Peloton’s revenues dropped from $4 billion in 2021 to $3.0 billion in 2022, and losses ballooned to $2.8 billion. The stock also took a nosedive. Once boasting a $50 billion valuation, the company ended 2022 valued at just $11 billion.

The former CEO John Foley also felt personal repercussions as he listed his $55 million Hamptons mansion, purchased just a year earlier, at a loss, a symbol of the financial toll that Peloton’s downfall had taken.

The equipment issues

The repercussions for John Foley were just monetary, but consumers sometimes faced something far more severe. In March 2021, a devastating incident involving Peloton’s Tread+ treadmill came to light, in which a six-year-old child lost their life after getting entrapped in the treadmill. This tragedy was only the tip of the iceberg.

By this time, Peloton had already received over 150 reports concerning the Tread+ defects, with incidents including individuals, pets, and objects being pulled under the rear of the treadmill. Eventually, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) revealed that Peloton had knowledge of these issues as early as December 2018 but did not report them promptly.

As part of a settlement with the CPSC, Peloton agreed to pay a $19 million civil penalty for failing to report the defects and for distributing recalled treadmills.

The subsequent recall of the Tread+ treadmill affected approximately 125,000 units, which was effectively all of the units sold to date. It was brought about by the mounting evidence of the product’s risks, including abrasions, fractures, and even death.

Peloton’s issues extended to its bikes as well. In 2023, a recall was issued for the original model Peloton Bike due to the seat post snapping at the weld point in some instances. There were 35 reported incidents concerning approximately 2.2 million original Peloton Bikes sold in the US.

The scale of these recalls added a significant burden to Peloton’s inventory problems. While Peloton had ramped up production to meet the high demand during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand began to wane. The combination of massive recalls and inventory build-up cast a shadow over the company that was once hailed as a game-changer in the fitness world.

Wrapping it up

So let’s wrap it up.

Now, if Peloton were a human, it’d be that person who won the lottery, went berserk buying yachts and gold-plated toothbrushes, and then wondered why they’re broke a year later. Like a fitness fad diet, Peloton went from the McDonald’s of home gyms to the leftover stale fries under your car seat. It’s like their business strategy was sponsored by Red Bull – they got wings, soared high, and then realized they were Icarus.

Now, it’s not like they didn’t see the treadmill train wreck coming. But when you’re doing lunges on a golden treadmill in the Hamptons, it’s hard to notice the cliff you’re lunging towards. Peloton’s CEO John Foley? He bought a mansion next to Jerry Seinfeld, and then had a real-life episode of “Curb Your Enthusiasm” – a comedy of errors that made the stock price whimper.

To be fair, the idea was brilliant: make fitness addictive, bring the gym home. But then, gyms opened back up and people wanted to actually leave their houses. I guess humans don’t just subsist on Wi-Fi and Peloton subscriptions.

Peloton seemed to think their hypergrowth would extend well past COVID and they need to ramp up like the growth would never end. Today they can’t give away Peloton’s and people are back in the classroom connecting with people in person.

It’s not to say Peloton doesn’t make sense for some people, it’s just no longer a hyper growth $50 billion company like it once was. The lesson here for young companies: don’t sprint on a treadmill thinking you’re running a marathon.

Information for this briefing was found via Reuters, CNBC, Bloomberg, and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.